Six months ago, the Denver Basic Income Project (DBIP) started giving cash regularly to people experiencing homelessness, no strings attached.

On Tuesday, the group released data on the halfway mark of the pilot program, showing that rates of homelessness and food insecurity decreased, while shelter and employment rates increased over the past six months.

While many government support programs come with spending restrictions and requirements, universal basic income gives people money outright, trusting people in poverty to know what they need most. The approach has taken off across the country, with many cities piloting a version of the program. DBIP spokesperson Abby Leeper Gibson said in a statement Monday that Denver's study is the largest in the country.

DBIP began giving cash payments to around 800 people experiencing homelessness in December.

The project split participants into three groups: people who receive $1,000 per month (group A), people who receive $6,500 up front and $500 per month afterwards (group B), and people who receive $50 per month as a control group (group C).

The three groups mirror the racial and gender demographics of people experiencing homelessness in Denver. According to researchers, respondents to the six-month study were more diverse in gender identity, race, ethnicity and sexual orientation than the latest Point-In-Time count of homelessness in Denver.

As a pilot program, the purpose of the three groups was to study and compare outcomes, in partnership with researchers from the University of Denver.

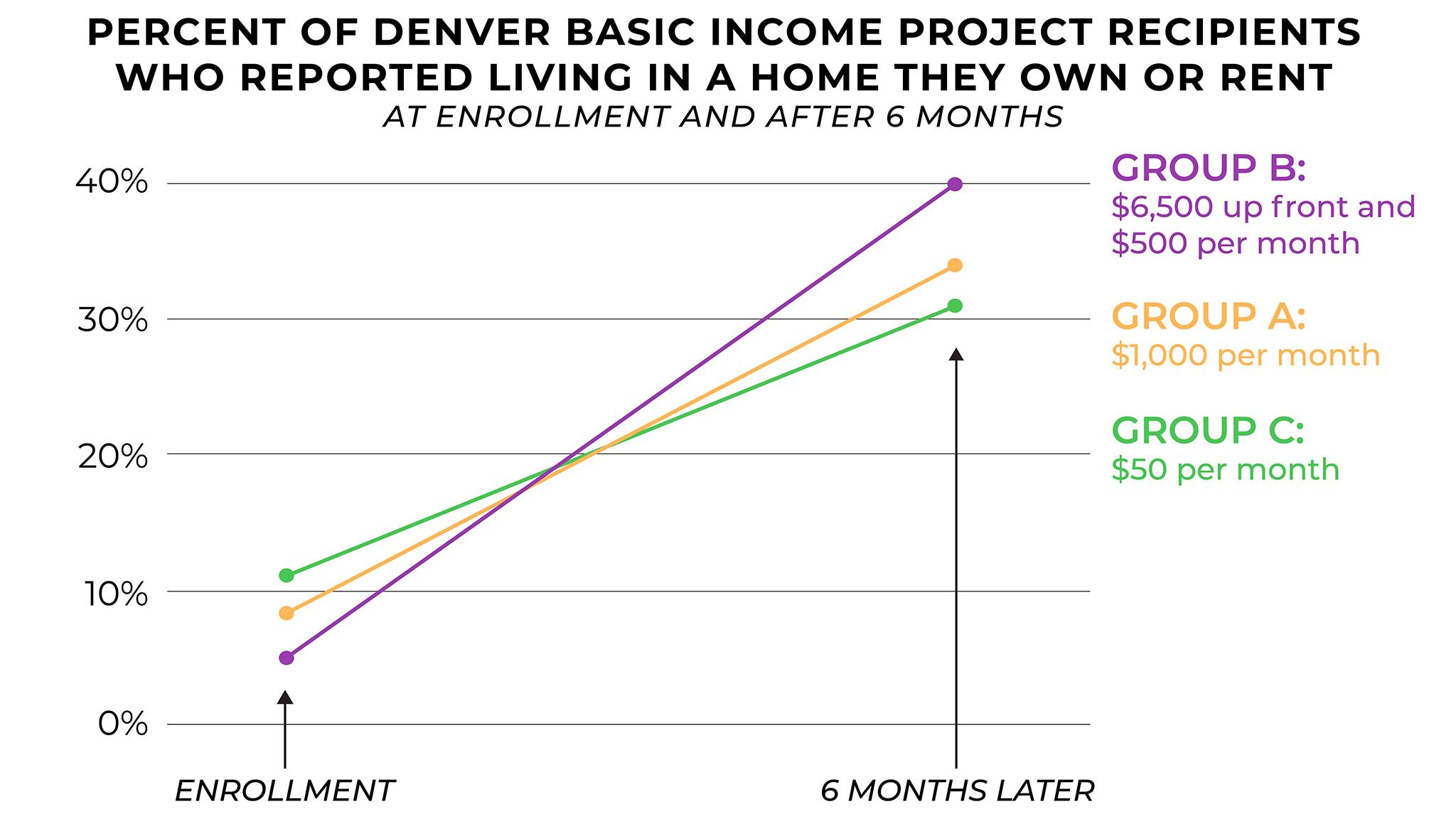

Halfway through the program, preliminary results are here. Here's how rates of people living in housing they rented or owned changed:

- Group A reported a 26% increase in participants staying in housing they rented or owned;

- Group B reported a 35% increase in housing they rented or owned;

- And Group C, which received the smaller sum of money, reported a 20% increase in renting or owning housing.

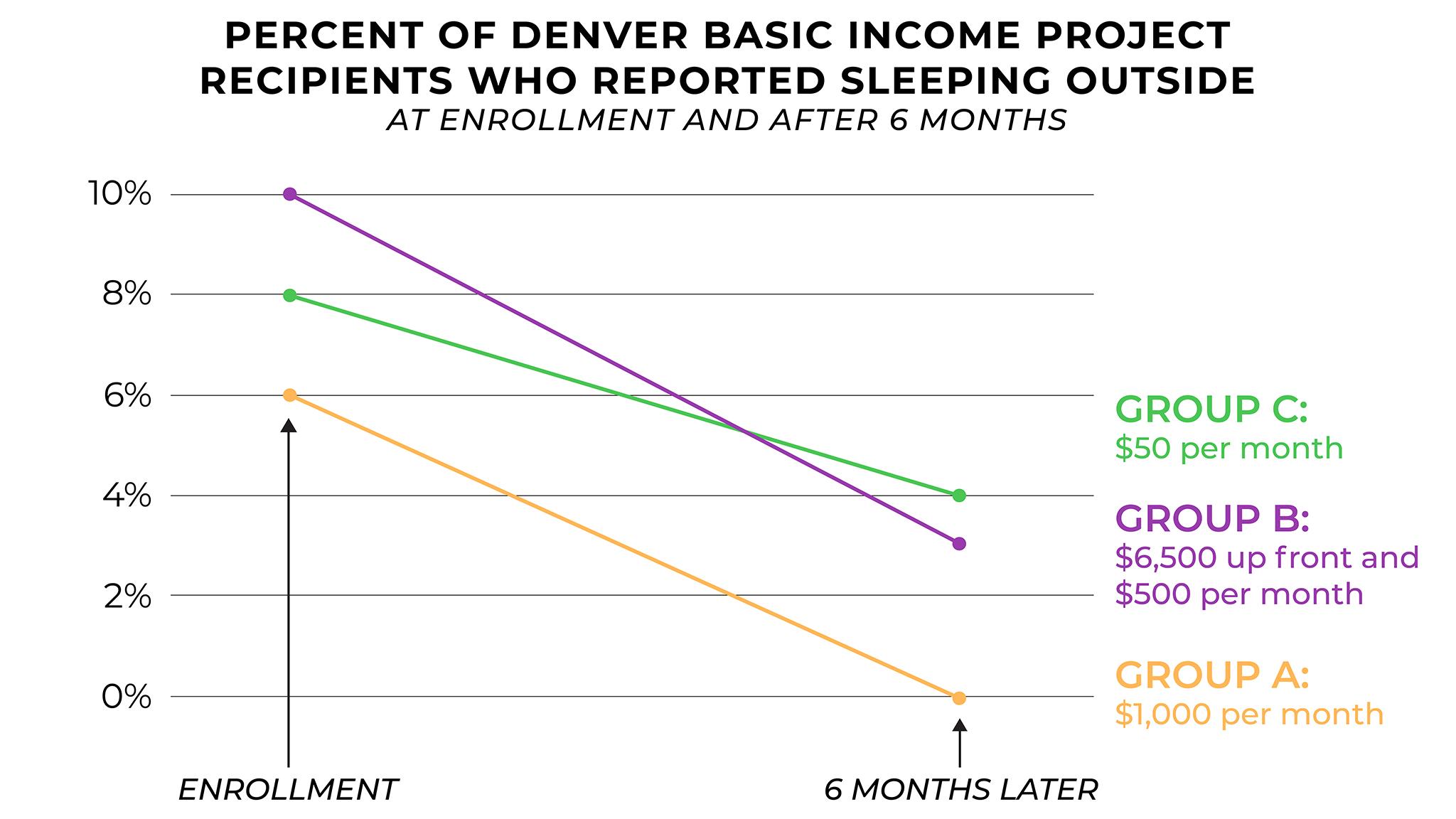

The groups also reported sleeping outside less often:

- In, Group A unsheltered homelessness rates dropped from 6% to 0%;

- Group B's rate fell from 10% to 3%

- And among Group C, that figure dropped from 8% to 4%

Rates of shelter stays decreased as well, dropping from 23% to 10% for the group as a whole.

"The data is supporting what we're hearing directly from our participants - that cash payments, even in a short amount of time, can improve lives for the better," said DBIP Founder and Executive Director Mark Donovan in a statement Tuesday.

The study measured a number of other factors, including food insecurity, mental health and feelings of safety.

Overall, the two groups receiving the larger sums of money said they felt safer at night and more welcome where they slept than before the cash payments, while the group receiving the smaller sum said they felt slightly less safe at night compared to six months ago.

"On average, everyone felt more confident about their future housing," the DU researchers wrote in the report.

Groups A and B also increased their full-time employment, a figure that remained unchanged for people in group C. All three groups reported that they experienced decreased food insecurity over the course of the six months. However, researchers did report that all participants showed declines in overall mental health.

In July, DBIP released an initial qualitative report, with a number of testimonies from program participants. Many people talked about securing housing, paying off debt, supporting children, feeding themselves and saving money for the first time. That initial report showed "significant benefits" of universal basic income for people experiencing homelessness.

"It's easy to dismiss when it is someone else's struggles, but the right crises can cause many of us to lose everything," said April Marie, a program participant, in a statement Tuesday. "The DBIP family literally kept me alive this year, and I am forever grateful."

The study will release final results in six months. But beyond that, the future of the program is unclear.

"This report does not provide complete information on the impact of DBIP," researchers wrote. "The impact of DBIP will be assessed in a final report that will be available in June 2024"

However, the future of the program beyond summer of 2024 is uncertain. DBIP is currently funded through a mix of private donors and $2 million from the city, funded from federal pandemic recovery money. But those funds are drying up, and the city has not committed specific funding for the program in the 2024 budget.

"Transformation takes time and we need to extend this program for another 12 months," Donovan said Tuesday. "We call on Denver's elected officials to reinvest in this program so that we can continue supporting over 800 people on their path to thriving."