"There's some kids right here," a Denver Police officer said to his colleague as they approached a small encampment on Zuni Street, at Jefferson Park's northern edge. "They staying in a tent?"

"Not yet," the other officer said.

When Denver's first winter storm of the season lifted last week, so did a moratorium on kicking newly arrived migrants out of city-sponsored motels. One of these shelters was across the street from the collection of tents where the police officers found Carlos Alberto Jepez with his wife, two children and dog.

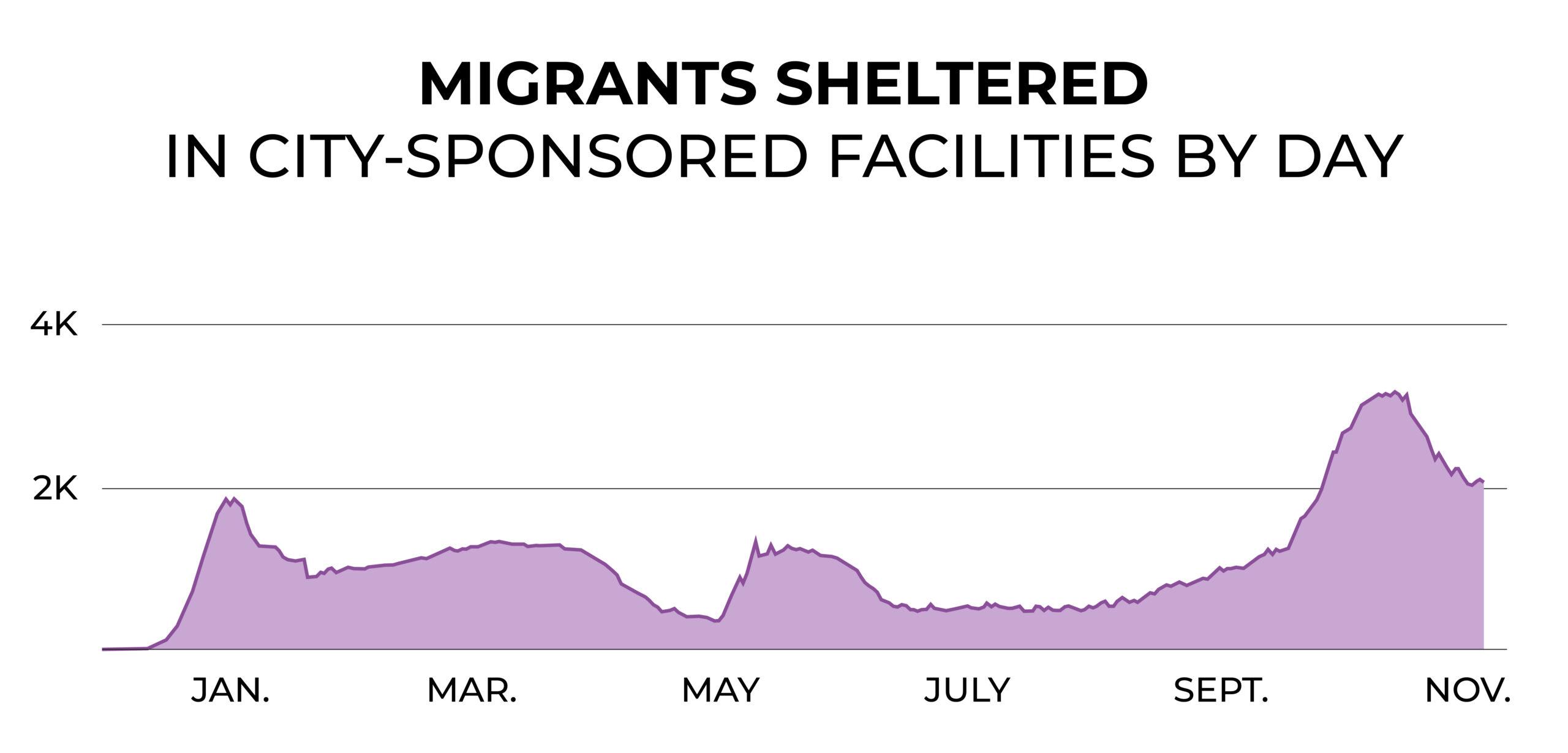

The city has housed thousands of people who have traveled from Venezuela and Colombia through the last year, giving them a few weeks of shelter before they have to make it on their own. But most people entering and exiting the city's system aren't allowed to work in the U.S., and many who came here looking for better futures have no idea what they'll do once they have to leave this safe space.

That was the case for Jepez, who expected to stay for another week in the room Denver provided to him. But shelter officials found the dog, Niña, who'd traversed jungles and deserts with the family on their months-long journey from Venezuela. Jepez's son suffered from depression, the father told the police, and this tiny animal was all he had to calm his nerves, so it was worth breaking the rules. Now the dog shivered in his arms as they wondered what they would do next. Jepez hoped he would be able to help himself by now.

"We don't know anyone. We don't have anything," he told the officers in Spanish. "I didn't come to beg on the street or anything. I came to work."

Money for shelters, and pathways to employment, were Mayor Mike Johnston's big asks during a short trip to the White House last week.

Johnston knows people are falling through cracks in the city's systems, but he also knows that Denver can't afford to shelter everyone forever. He told Denverite that Denver is on track to spend $100 million next year to provide short-term housing for people seeking work and asylum. Officials have voiced concern about the city's ability to pay for these accommodations since migrants began arriving in large numbers last year, sometimes ending up in Denver's regular homeless shelter system.

To address these concerns, Johnston flew to Washington, D.C. last week, leading a group of mayors from Chicago, Houston, Los Angeles and New York to ask President Joe Biden for help.

"We think the current path is unsustainable, but we think there is a way to really resolve this situation that works for the newcomers that are arriving and works for the cities that are receiving them. And for us, that focused on talking to the White House and the Senate and the House about, yes, increased federal funding for resources for cities, but also really increasing access to work authorization," he told Denverite.

While Johnston and the other mayors did not meet with Biden directly, Johnston said they were able to bend the ears of Biden's chief of staff Jeff Zients, senior advisor Tom Perez and Homeland Security secretary Alejandro Mayorkas.

On the fiscal front, Johnston said the delegation asked the president to more than triple the $1.4 billion he's asked Congress to provide to help cities accommodate migrants.

"We're really grateful the president has come out with a supplemental budget that had $1.4 billion for services for cities. We think that number needs to be closer to $5 billion," Johnston said. "That's just to reimburse the city for what we're currently spending, and it won't even reimburse all of that. That $5 billion number we gave will only cover about 70% of just the needs from our six cities alone, and so it will mean that the city is only picking up 25% of the tab instead of picking up 100% of the tab."

But pathways to legal work, Johnston told Denverite, would be more impactful.

"What we know is we have migrants who arrive in the city, and when I talk to them, the first thing they say is, 'Hey, I just want a job. Where can I get a place to work?' And I also get calls from employers every day who want to hire those folks," the mayor told Denverite. "We have people here who want to work. We have employers who want to hire them. We have a federal government standing in the way of that transaction happening. And so we want to really push them to expand work authorization, to accelerate the processing of these asylum cases."

In recent months, proposals have floated through the House and Senate to change how work authorization is doled out in this country, but the issue's divisive nature and ongoing gridlock in Congress may block the fixes Johnston and his mayoral colleagues have requested.

"If we don't have the capacity for people to work, there will always be a moment at which they're going to not be able to survive without ongoing public support. And we know it's not possible for us to provide perpetual public support," Johnston said. "They're asking us for the chance to work, so we're trying to give them what they explicitly asked for."

For now, families like Jepez's are struggling to survive.

The police who found Jepez in the Zuni camp put his family in a different hotel for a few nights, to keep his kids off the street. One officer, who did not give their name because they were not authorized to speak to press, said they have found so many families with children sleeping outside that they recently maxed out the credit card they have to shelter families.

Denverite has spoken to many more families who, like Jepez's, are trying to figure out how to survive here.

"I have six days left to leave and I don't know what I'm going to do ?," one woman who's staying in the Zuni motel texted to Denverite last week. She and her kids will be in a situation similar to Jepez's by Wednesday.

Jonalber Adonai Santander Fernandez spent three months traveling to the U.S. from Venezuela with his girlfriend and her family. Everyone else in his group qualified for a month in the Zuni motel. But because Fernandez isn't married, he was only allowed 14 days in the motel before he was sent out to manage on his own. In a few months, an immigration judge will decide whether he will be granted asylum to stay in the U.S.

When Denverite met him, Fernandez was standing on the corner, unsure what to do. The motel's managers gave him information on some places where he could pay for a place to sleep. The cheaper option was just $100 a week, but Fernandez said he couldn't afford that.

"My plans are to get a job. To settle in a rented house. It doesn't matter if it's here or somewhere else. Wherever. Wherever God puts you and where you have a good job, good stability," he said in Spanish. "The most worrying thing is where to sleep."

Isaac Vargas contributed to this report.