In December of 2018, the last of three lawsuits attempting to thwart Interstate 70's expansion through Elyria Swansea failed, but not before activists squeezed a promise out of the state.

While the project would - and did - carry on, those neighbors would get $600,000. Most was earmarked for a sweeping community health study to address the air pollution, noise, odors and illnesses that residents feared could be made worse by jamming more cars between their homes.

So the GES Community Health Study working group was formed, a partnership between residents of Globeville and Elyria Swansea (GES) and Colorado State University (CSU). In February, they published their first big deliverable: "The ABC's of GES: The State of Health and Environment."

This study is supposed to be different, in that it's meant for the people that it analyzes.

It's a dense document that covers everything from health access and outcomes to grocery stores and sidewalks.

Marshall Thomas, a recent CSU grad who's been managing the project, said authors gathered every relevant dataset they could find. They decided not to conduct any new surveys.

In their first year on the project, a community engagement phase, Thomas said they learned residents felt "overstudied" by so many researchers who came in to assess how badly they were underserved. Neighbors didn't usually get the results of that work, anyway.

Still, Thomas said there wasn't as much material to work with as they expected.

"We were surprised at what data is and is not available. We've heard a lot of the community members say they've been studied to death, and there's a lot of studies. But when we looked at it, there's not a lot of peer-reviewed literature out there," he said.

While some in the community weren't sure GES needed another health report, community members said this one was worth the effort. Candi CdeBaca, the former City Council member for this district who led the resistance to I-70's expansion, said it was the first research she could remember that really connected so many issues at once.

"It was supposed to be cumulative, and that was one kind of study that had never been done in our neighborhood. We got a lot of one-off studies without anyone ever putting them all together," she said.

It also represents a move towards more community power, since the report's authors have emphasized the results ultimately belong to residents. Some in these neighborhoods have been consolidating that power for years, as they bought land for affordable housing and protested unwelcome development.

Rebecca Trujillo said she shares her neighbors' frustrations that her neighborhood has been analyzed over and over, but she sees this as an opportunity to build that collective strength.

"What they are going to do is provide us with the tools, that we can be a voice in our own community," she said.

The report shows what Globeville and Elyria Swansea residents know: they are less healthy and have less access to the things they need to be healthy. Still, some measures weren't as bad as they expected.

Let's start with the basics.

Over 70% of Globeville and Elyria Swansea residents identify as Hispanic/Latino, compared to 30% across the rest of the city, authors wrote. The neighborhoods are younger, too: 25% of residents there are under 18, compared to 20% in Denver as a whole.

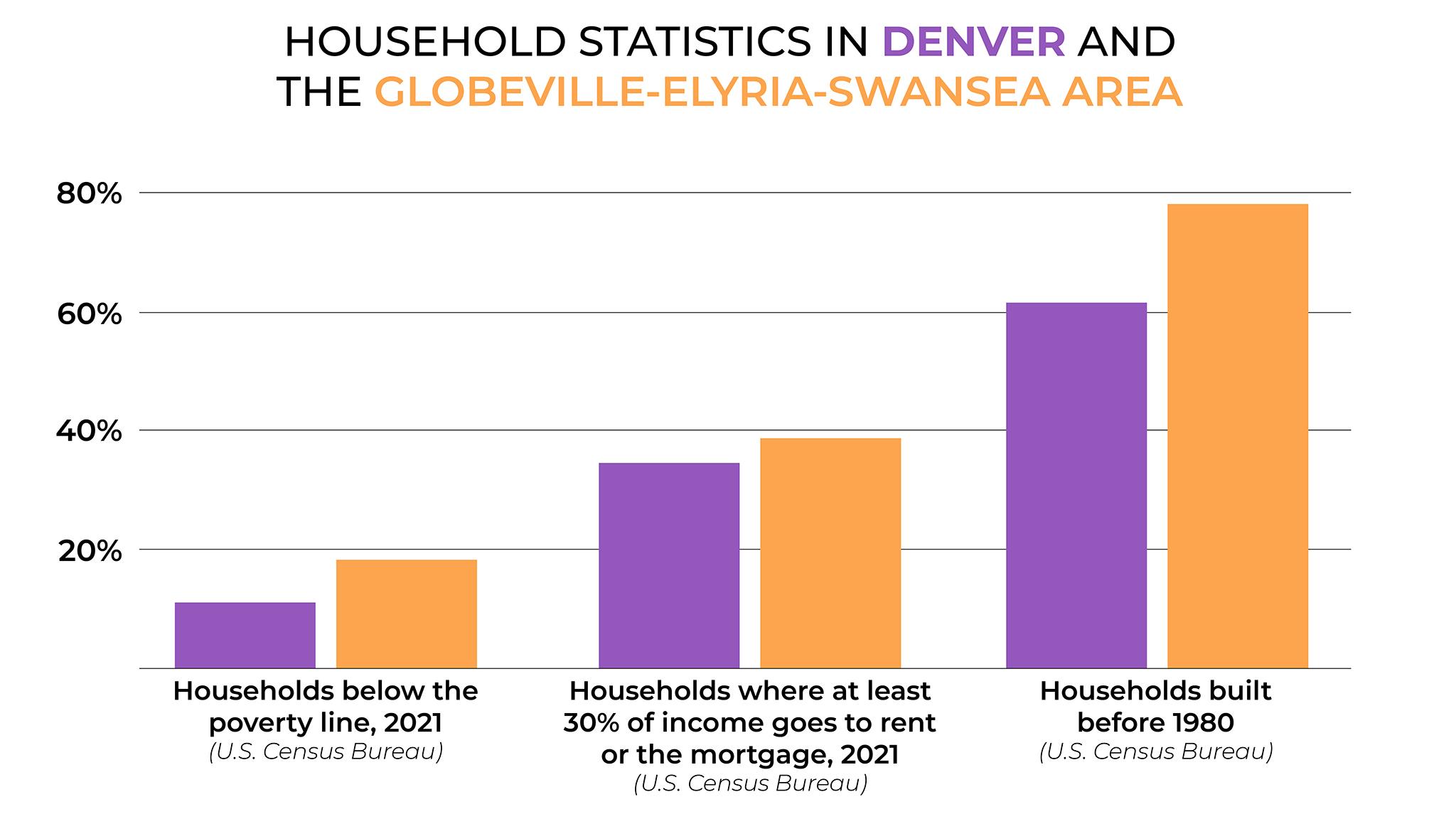

Household income in the combined GES area is also more likely to be below the poverty line, and residents are more likely to spend more than 30% of their incomes on housing, which means the federal government considers them "cost burdened."

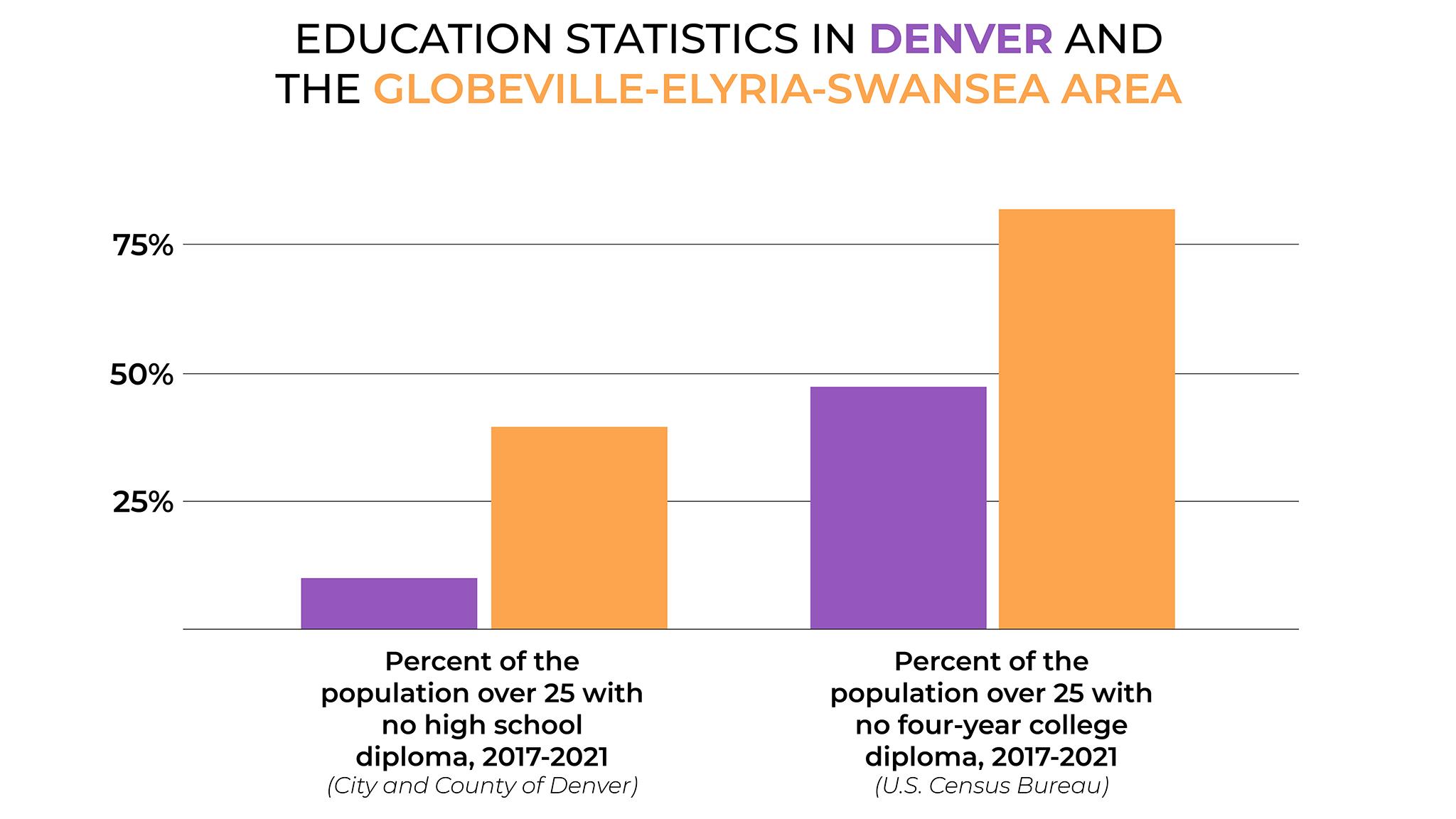

Residents of the combined GES area are also less likely to have high school or college degrees, compared to the rest of the city, one stat that's contributed to a larger discussion about Denver's "Inverted L" shape that shows inequality in the city.

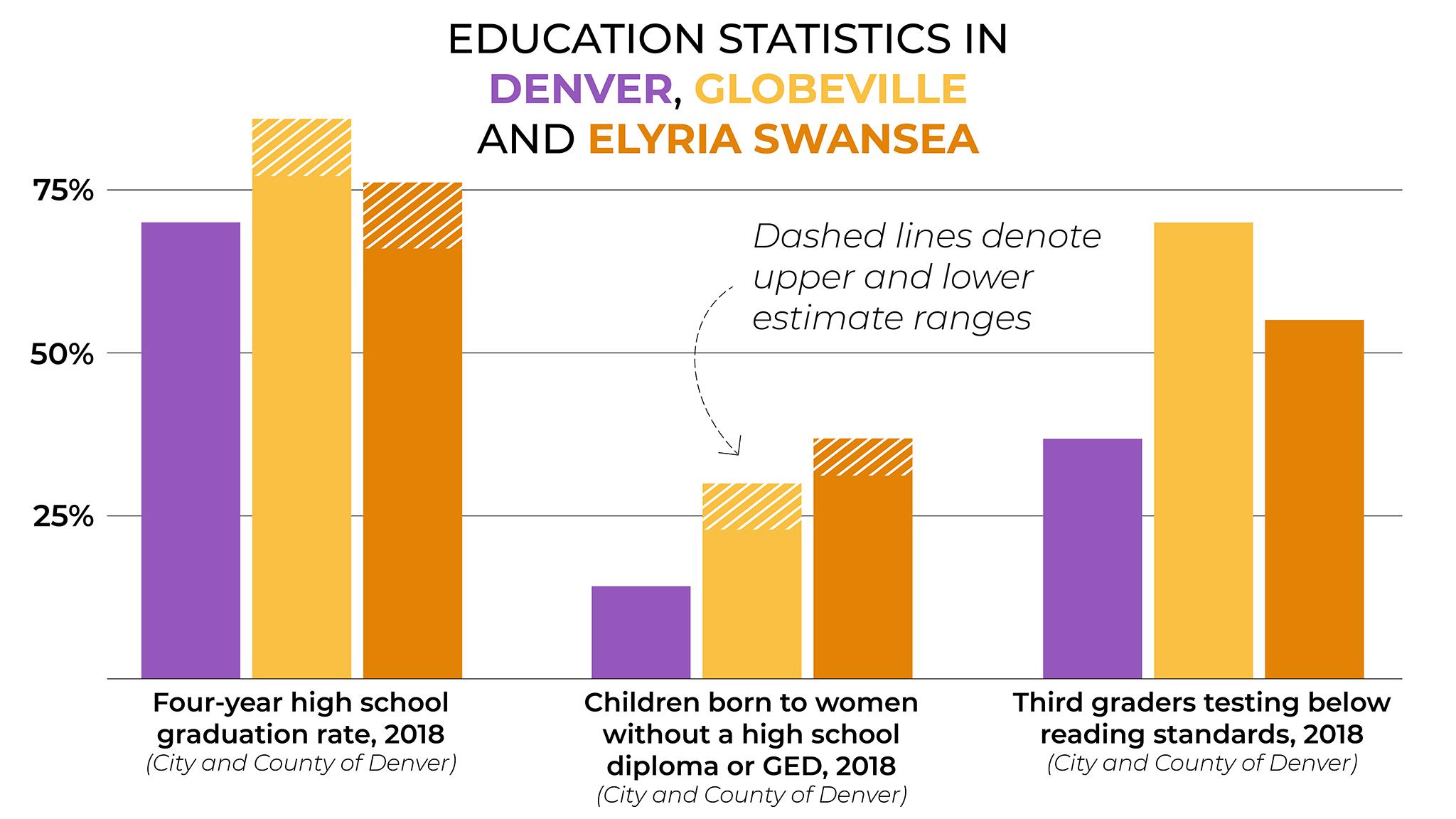

And while young students in GES tend to be behind their peers - which we can see in third-grade reading levels - high schoolers in these neighborhoods graduate at higher rates than in the city at large.

So, there is some good news on education. Still, authors suggested that more needs to be done in this arena.

"Educational attainment not only influences life expectancy, but also impacts employment, income, and other social determinants of health," the authors wrote. "Without quality, affordable, proximate education facilities, GES residents will continue to face a disproportionate burden in fulfilling this basic health need."

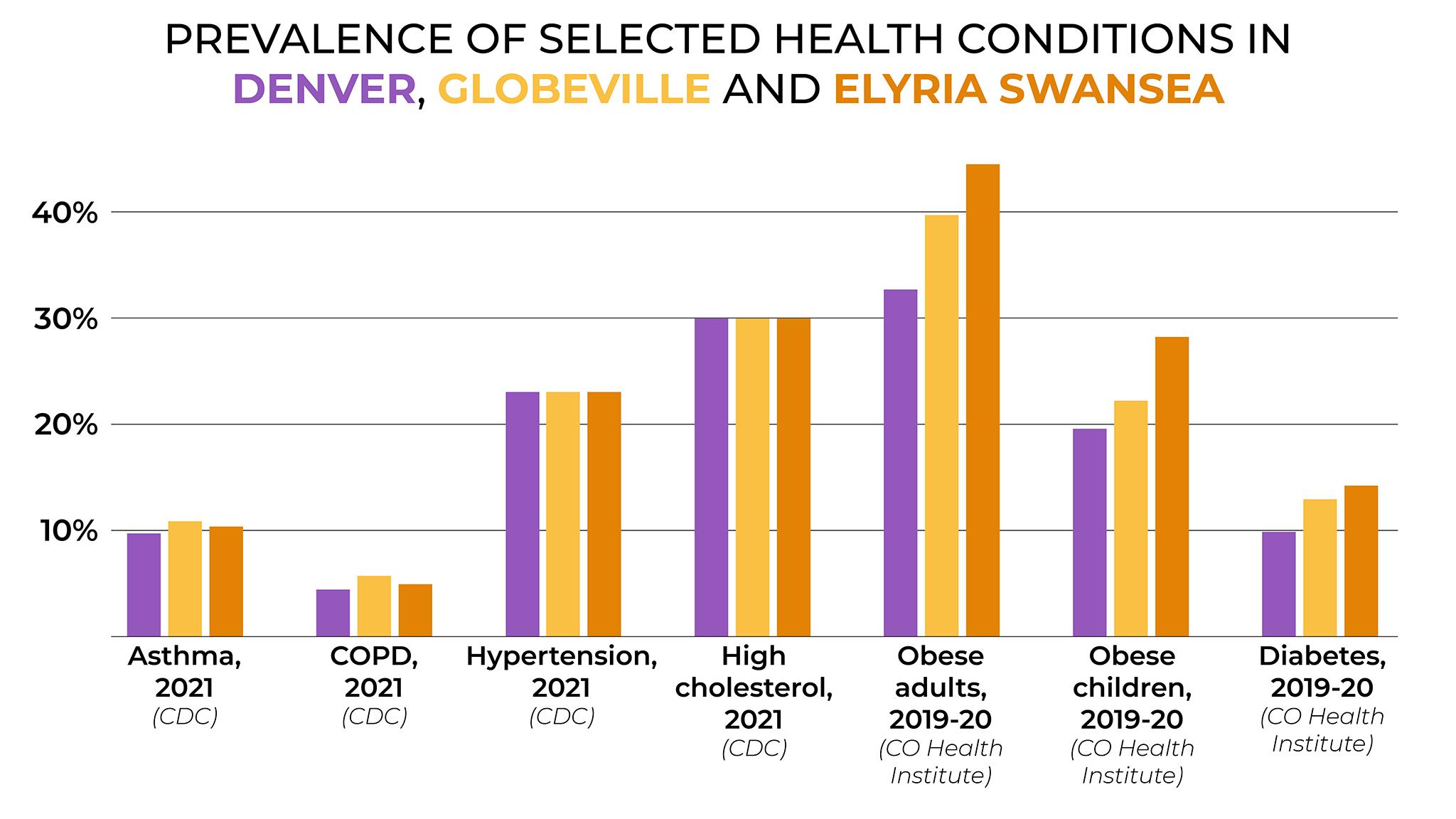

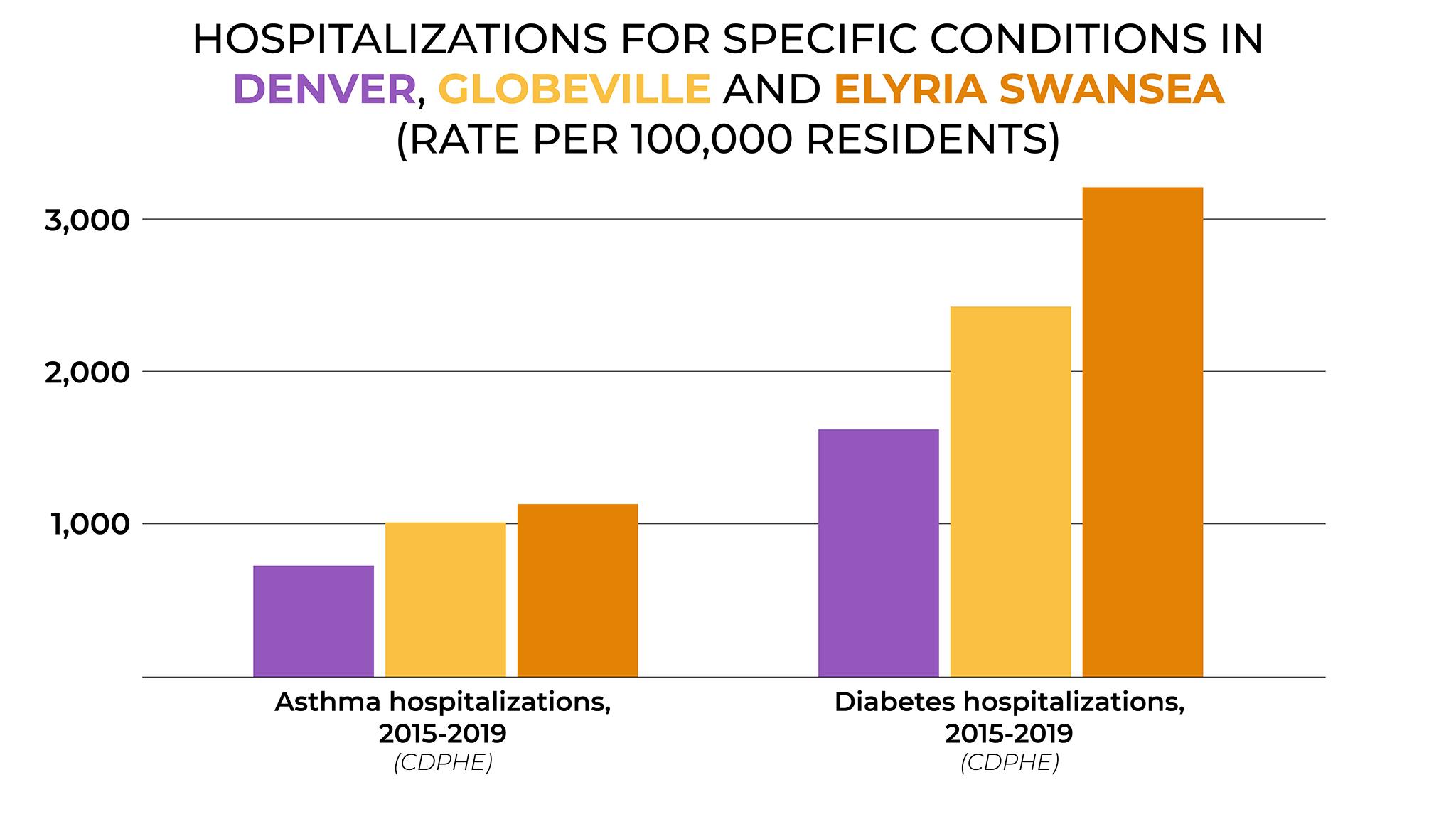

Data on health outcomes show GES residents experience obesity and diabetes more often than their neighbors across town, but some numbers suggest that neighbors' biggest concerns - cancer, asthma and cardiovascular conditions - may not be as bad as they think. For example, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention pegs asthma prevalence around 10% in Denver and both neighborhoods.

But researchers dug in more, and found hospitalization numbers for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) show GES residents are still suffering more from these conditions.

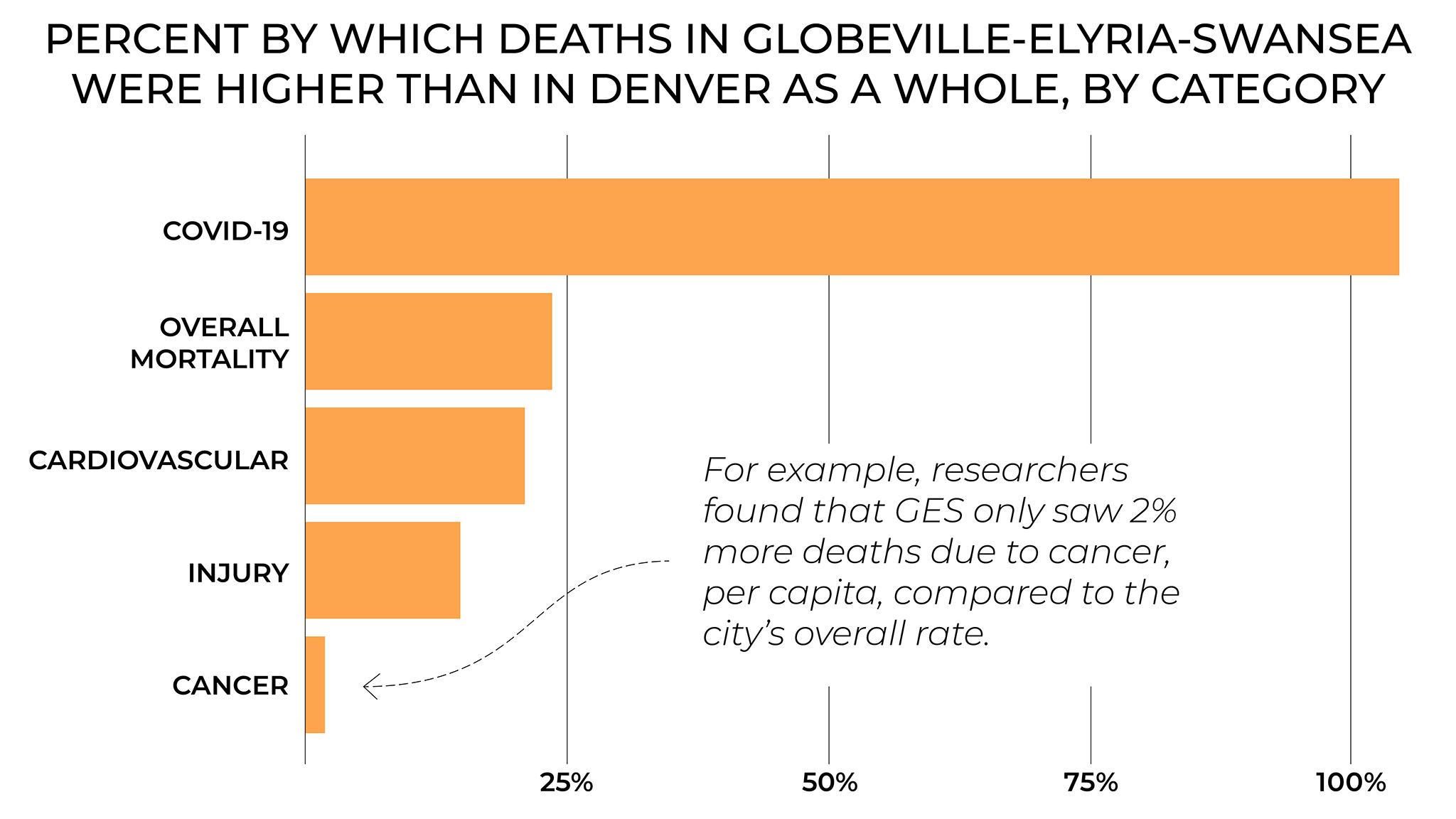

The authors also crunched mortality data on their own, creating an index to compare deaths in GES to those across town. Their calculations suggest over 100% more people in GES died from COVID compared to Denver as a whole - per capita - and that overall mortality is about 25% higher in those neighborhoods than the rest of the city.

Residents of the combined GES area only died of cancer 2% more often than in the city at large, though, a fact that some neighbors said was surprising when initial results were discussed at a public meeting in January.

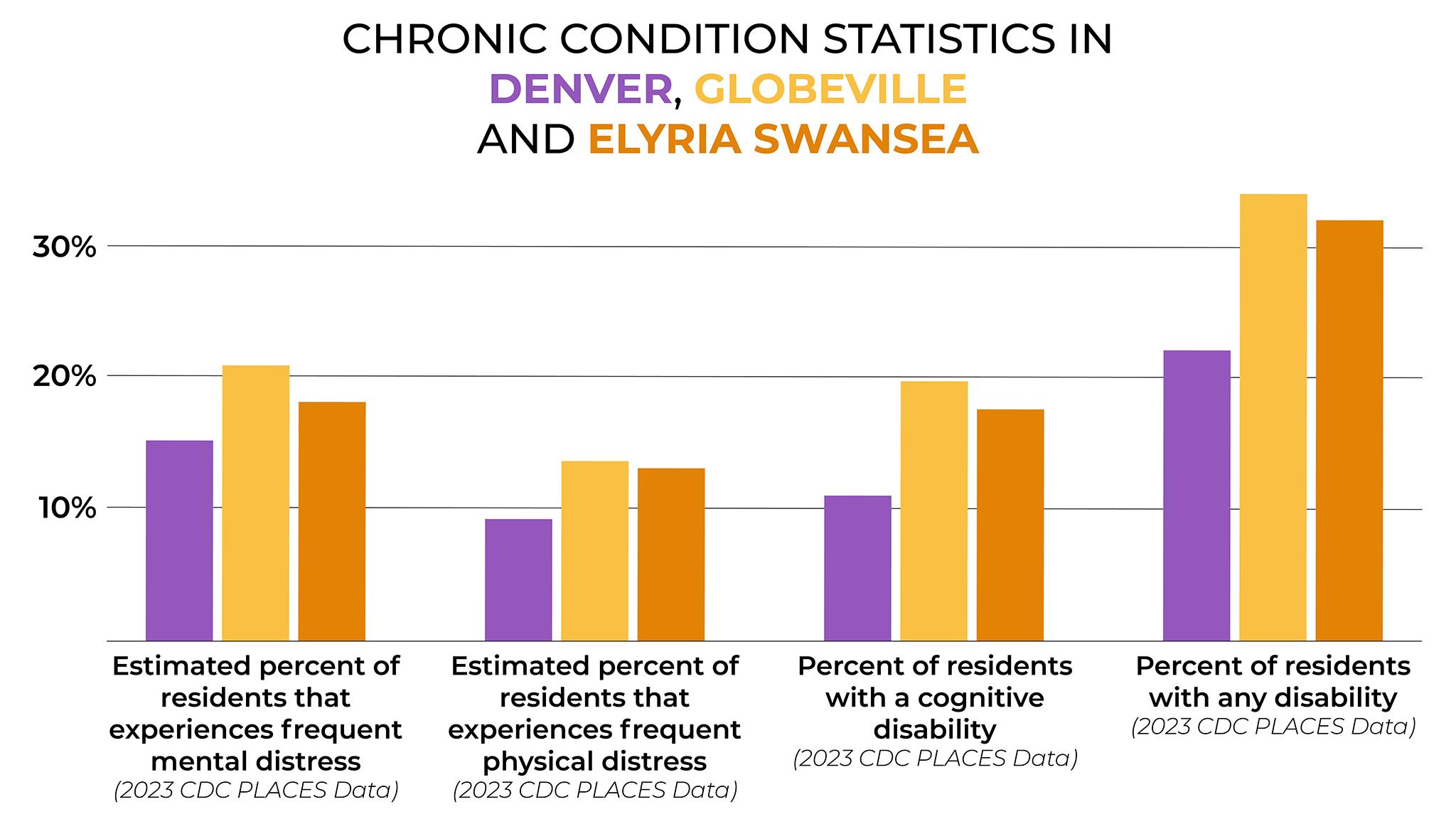

GES residents are also more likely to deal with chronic conditions than their neighbors.

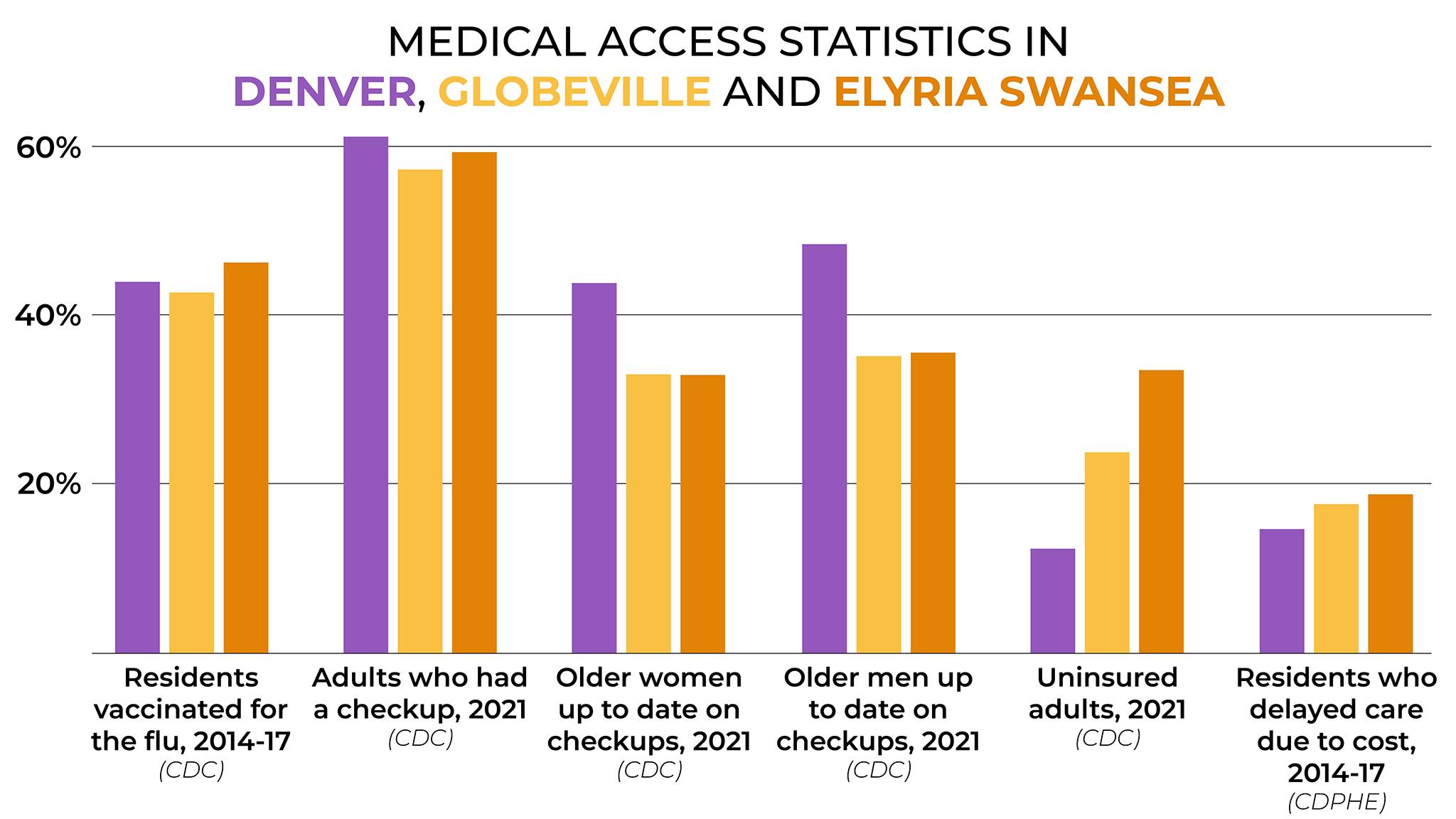

And while GES residents do get vaccinations and annual check-ups at similar rates to their neighbors, they do so despite having less access. Elyria Swansea residents, in particular, are 20% less likely to have health insurance than in the city as a whole, and all GES residents are more likely to delay care due to cost.

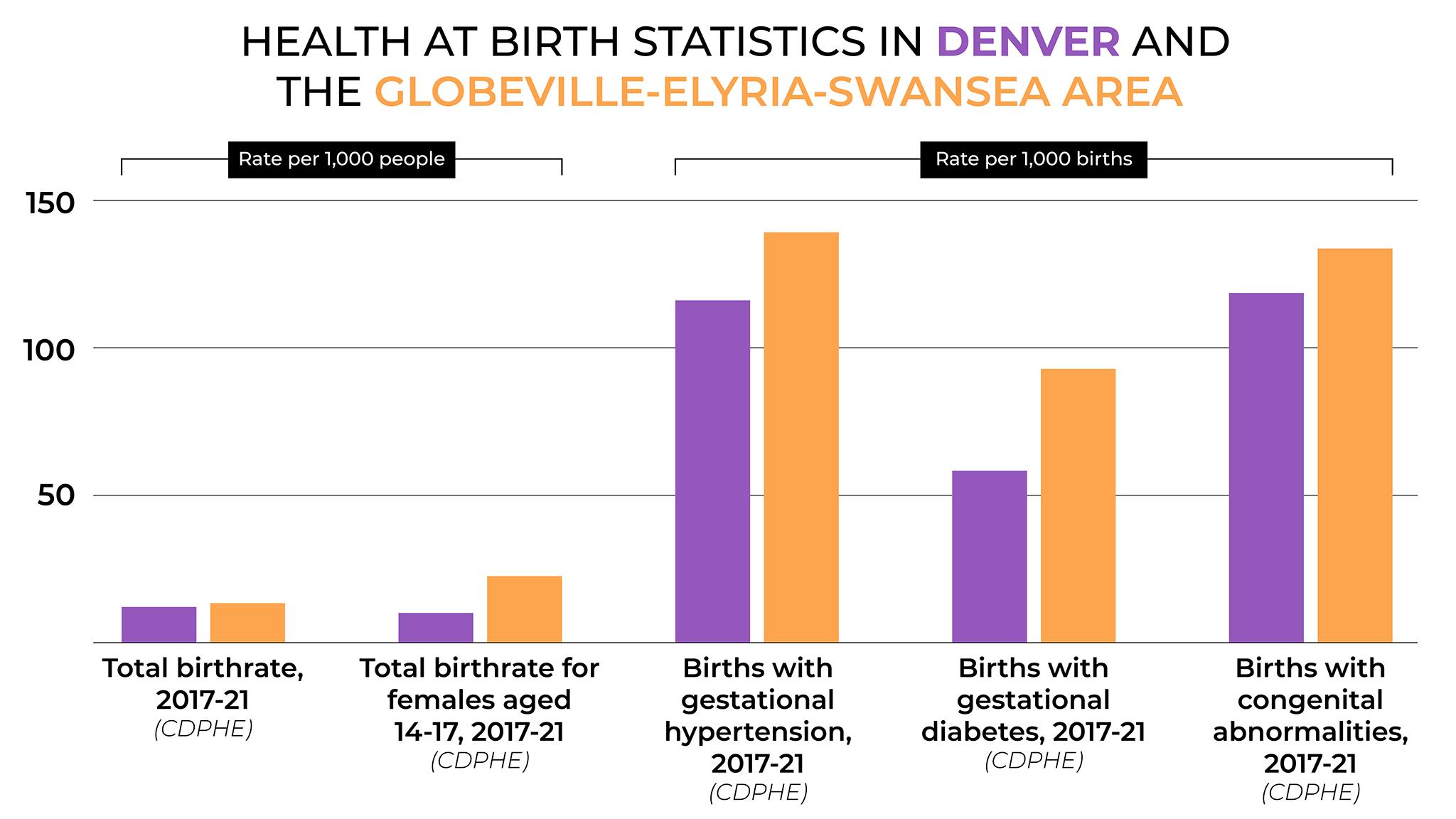

Data on health conditions at birth similarly show disproportionate rates of gestational diabetes and hypertension, which authors said was "substantially" higher than the city at large. They did not find differences in rates of low birth weight and preterm births.

While this report generally avoids talking about what may cause disparities, the authors do suggest that environmental issues could play into these birth numbers - though they can't say for sure. Their report also fleshes out soil, water and air pollution data, but their analyses didn't reveal any new smoking guns when it comes to harmful exposures.

Air sensors, they wrote, generally showed pollution below Environmental Protection Agency standards, with a few exceptions, though a separate study from the University of Colorado Boulder did recently suggest that air pollution is more of an issue for Denver's communities of color.

Throughout each section in the study, authors took pains to show how this is all connected. If you're poor, if you're uneducated, if you don't have sidewalks in your neighborhood, you may not have the time or space to exercise and keep healthy. It's an attempt to show how structural issues - like the fact that 0% of Elyria Swansea residents live within walking distance of a grocery store - might show up in diagnosis numbers.

Next, the working group plans to dig more into those causes, and see if they can calculate, for example, how much asthma can be blamed on the highway, or nearby industry. That report is slated for January 2025.