Previously, Denverites using the city’s 311 customer service chat system could wind up on hold for 15 minutes waiting to chat with an agent to resolve an issue.

Now, the chatbot — newly named Sunny — responds almost immediately and speaks 72 different languages. That’s because Sunny is powered by artificial intelligence.

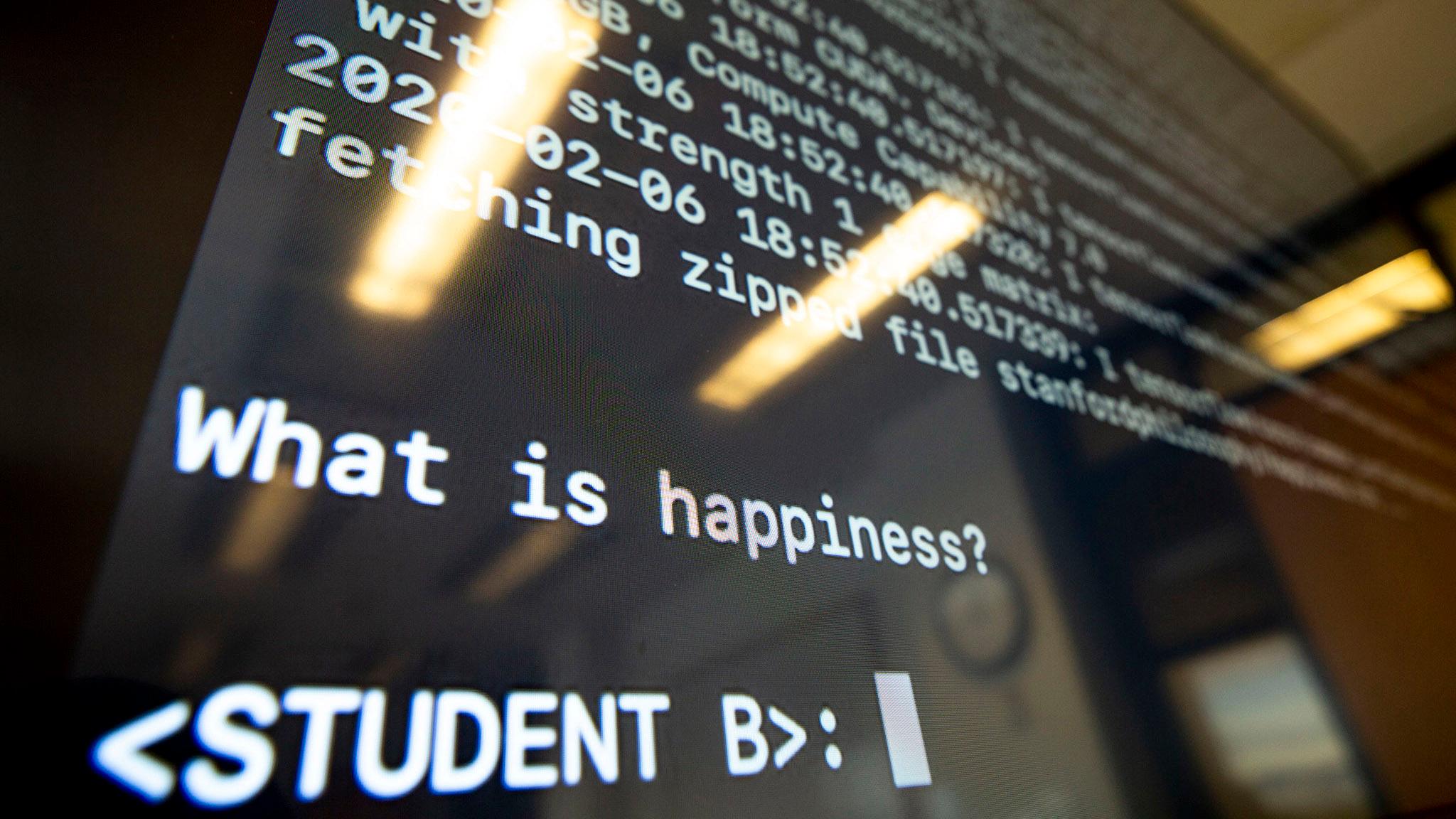

AI seems to have taken over in the past two years, ever since OpenAI first rolled out ChatGPT to the public in the fall of 2022. It has the potential to touch nearly every aspect of life — and not always in good ways.

Teachers worry about students using ChatGPT to cheat, writers are concerned about copyright violations, actors fear their image or likeness will be used inappropriately — and many others say the technology threatens their job security.

But so much of AI development has happened in the private sphere. How — and when — will Denver and other cities incorporate artificial intelligence into its operations? To what benefit, and what cost?

The answer: It’s already happening.

Denver has a handful of AI systems up and running you may have never noticed.

On Monday, city leaders sat down for a panel at the University of Denver to discuss how AI could shape the city of Denver.

Suma Nallapati, the city’s chief information officer, explained the ways AI already operates in the city.

One automated system speeds up the city’s system to pick up and haul off residents’ old electronics for recycling, generating a coupon for the program in a day rather than the old turnaround time of two weeks. Another program speeds up print jobs with fewer errors for Arts and Venues. Yet another automatically generates reports for building inspectors, bypassing a few hours of staff work gathering information.

Nallapati said the goal is to free staff from mindless work so that they can focus on the skilled parts of their jobs while saving themselves time.

“When it's taking away a lot of the mundane tasks, taking away the soul-sucking work, that's good,” she said.

Denver leaders only expect the city’s AI use to grow.

Adeeb Khan, executive director of Denver Economic Development and Opportunity, imagined how the city could use AI to speed up asylum applications for new immigrants, a process that currently involves hours of one-on-one legal support.

“The mayor, his team … are looking at AI solutions that exist right now that are able to help individuals navigate that in a more easy way and in a batch way where we work with a lot of people at the same time,” Khan said.

Khan also said the city could use AI to improve car and bus flow, potentially reducing collisions and improving traffic. He also pointed to trials in other cities experimenting with using AI transcription software to help 911 dispatchers.

But like so much new technology in the past few decades, new programs also bring new risks.

The public roll-out of AI has been full of dystopian stories about the technology — fake Facebook profiles of people purporting to give personal advice, a chatbot that sounds like Scarlett Johansson without her permission, racial bias and other prejudice baked into AI models, the worry that artificial intelligence will make entire careers obsolete and lead to unemployment.

That’s not to mention the broader concerns around data privacy, copyright lawsuits and misinformation.

Nallapati did not shy away from the numerous concerns when it comes to AI. From her perspective, tech companies will march ahead without the input of public leaders and everyday people whose lives and careers could be affected by artificial intelligence.

To her, that’s why Denver should get in on the action.

“Companies like Workday, Salesforce, Microsoft, they are using AI, whether we like it or not,” Nallapati said. “Do we educate ourselves more so that we can use it the right way, and not be the victims of someone else using the technology? They're using it no matter what, whether we like it or not.”

Nallapati said the city also is working to build in systems to combat common AI concerns around things like copyright and privacy.

The 311 chatbot, for example, only operates with information already published on the city’s website, not the internet broadly. Nallapati said she thinks cities have a better track record of responding to the public’s privacy concerns than tech companies.

“In public sector, there's at least a little more responsibility with data because of the agencies, the governance,” she said. “People complain about red tape, there is a need for red tape in some cases, because it's those checks and balances that protect your data that may not exist in the private sector to the same extent.”

Still, Nallapati recognizes that concerns about AI linger.

“The question that I get asked is, ‘Is technology going to replace humans?’” she said. “If we let it, it will, but we should be in charge.”