Denver launched a taxpayer-funded ad campaign last week to tell people they are not powerless in the fight against climate change.

They can, in fact, do something.

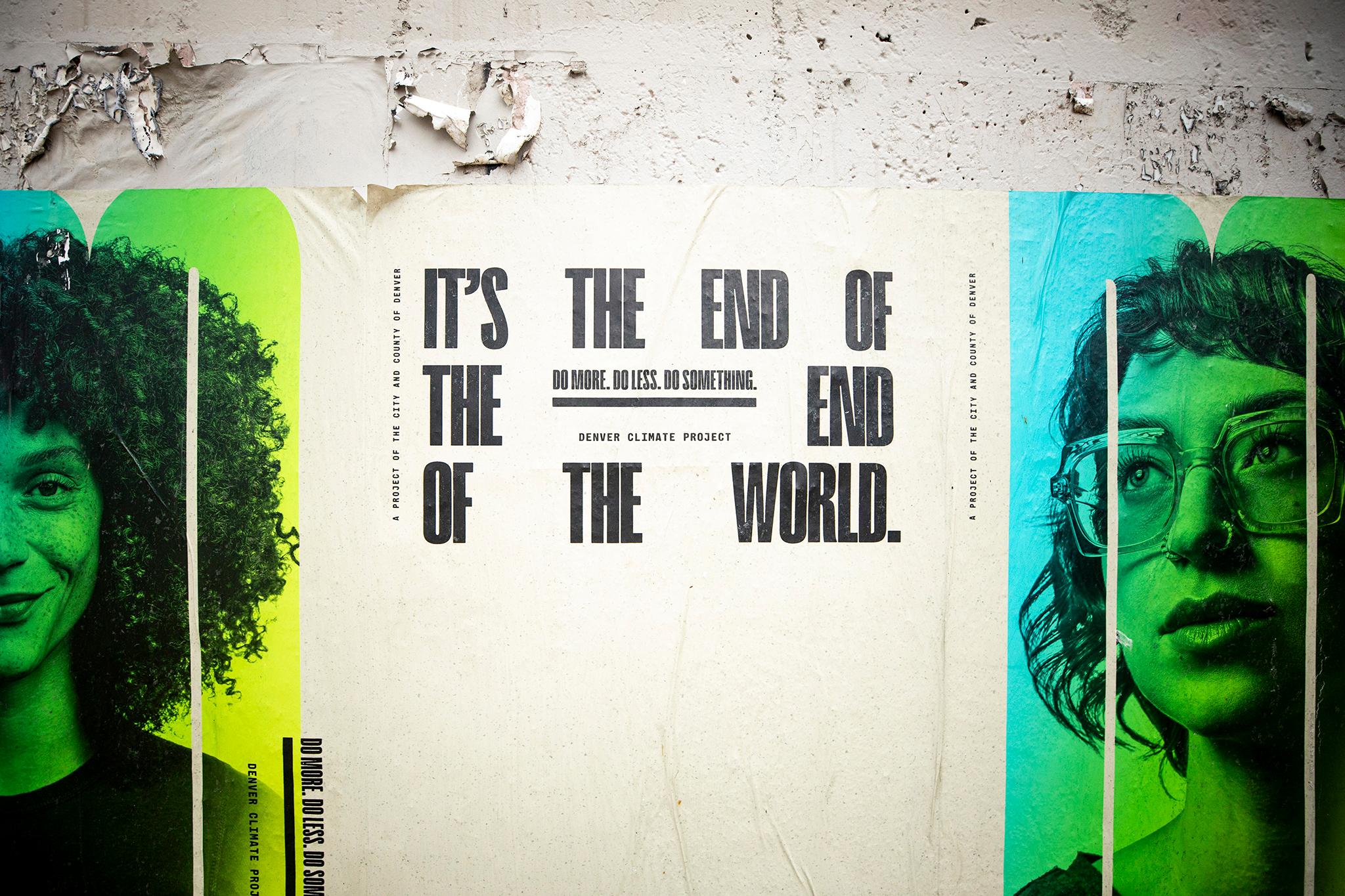

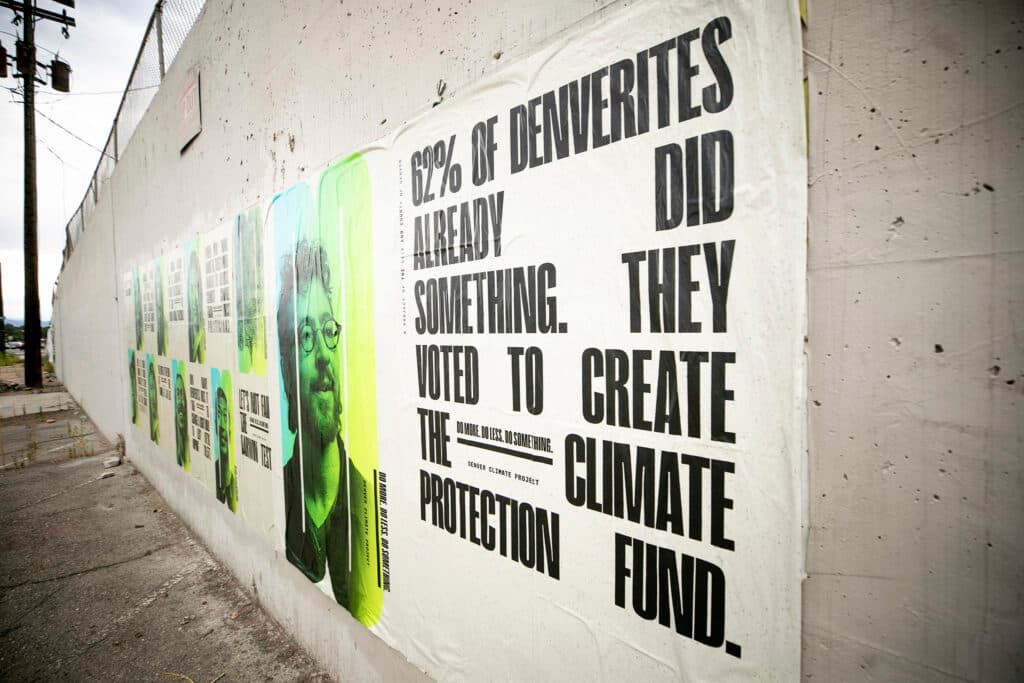

The ads are now plastered onto billboards, bus shelters and social media feeds across the Mile High City. Posted in Spanish and English, the images feature stylized green and blue photos next to the campaign’s tag line: “Do more. Do less. Do something.”

Some ads display bikes or electric cars to hint at ways Denver residents might assist the city’s broader environmental efforts. Others feature portraits of resolved and happy people next to messages like “not today, apocalypse” or the word “doom” edited down to “do.”

(Don Draper lights a cigarette and nods approvingly.)

The $3 million campaign will run throughout the summer and could return next year pending the city’s ongoing budget conversations. It's designed to make climate action appear more visible and widespread, replacing environmental fatalism with a sense of community-wide climate momentum.

Its most immediate impact, however, has been to split the city’s leading environmental advocates. While many support the campaign, others would rather Denver spend its limited climate dollars on more concrete projects.

“A lot of people want to walk and bike and take transit more. The reason they don’t is that it's not safe or practical,” said Jill Locantore, the executive director of the Denver Streets Partnership, a pedestrian and transit advocacy group. “It’s a waste of money to tell people to do something they aren’t actually able to do.”

Denver’s climate leaders think marketing is an important climate solution.

The fossil fuel industry has a long history of using ads and public relations to delay climate action.

In one famous example, BP spent more than $100 million on a campaign encouraging individuals to calculate their carbon footprints. Critics like historian Naomi Oreskes claim the ads helped introduce the public to the concept of “carbon footprints” so corporations could offload responsibility for climate change onto individuals.

“Obviously it's a very powerful tool because if it wasn't, they wouldn't be investing so much money in those types of efforts,” said Elizabeth Babcock, the executive director of Denver’s Office of Climate Action, Sustainability and Resilience.

Multiple studies have found the oil and gas industry spends far more on ads and public relations than other industries. In Colorado, Coloradans for Responsible Energy Development, an advocacy group funded by the state’s biggest oil and gas producers, spends more than $8 million every year on an ongoing “awareness and education campaign" about the benefits of oil and gas.

Babcock said Denver’s campaign is a small attempt to counteract that messaging, which she thinks has helped “distract” the public from reasonable climate solutions. She also rejects any suggestion the campaign is a waste of public funding, noting earlier advertising campaigns have successfully discouraged cigarette smoking and promoted water conservation.

The campaign and other city climate efforts are funded by a .25 percent sales tax voters approved in 2020. At the time, some critics said it was wrong to fund climate projects with a “regressive” tax that disproportionately impacts less wealthy Denverites.

Since then, the city has used the roughly $45 million annual revenue stream to offer residents popular e-bike rebates, plant hundreds of trees, install solar systems and shift buildings away from fossil-fuel-powered heating and cooling.

In response to Locantore’s criticism, Babcock said her office has considered using its limited climate funding on bike lanes and public transit. It opted against the idea in favor of less expensive projects expected to deliver faster emission reductions.

“You could put all of your dollars into one project that wouldn't transform all of the different systems we're trying to look at,” Babcock said.

Other climate advocates see the ad campaign as an important piece of Denver’s bigger climate efforts.

Environmental advocates have long debated the merits of pushing individuals to take climate action.

Climate scientists have cited driving, flying and eating meat as behavior that drives climate change. At the same time, critics argue that voluntary lifestyle changes won’t make a significant impact and might sideline efforts to demand accountability from corporations and governments.

It’s a conundrum Ean Thomas Tafoya doesn’t worry too much about. As the state programs director for the environmental justice group GreenLatinos, he said it’s possible to respond to climate change in day-to-day life and advocate for collective action. That’s why he’s glad an extensive list of recommended climate action published through Denver’s campaign includes a suggestion to “vote for climate-conscious leaders.”

“I just want to remind people that they can also participate in public hearings, that they can submit emails and written comments,” Tafoya said.

Tafoya also said Denver’s existing climate prgrams—like its e-bike and heat pump rebates—depend on residents knowing about them. He’s glad the campaign takes a multilingual approach to encourage individuals to participate in existing city programs.

The new campaign is meant to create a city-wide sense of shared responsibility.

Denver hired Sukle, a Denver-based creative agency, to produce the ad campaign.

Out of roughly $1.8 million spent on the campaign so far, about half has gone toward fees for the agency, according to Chelsea Warren, a spokesperson for Denver’s climate office. The city spent the other half on paid media, events, partnerships, branded installations and a pre- and post-campaign survey.

Sukle is well-known for designing Denver Water’s signature orange ads, which debuted in 2006, asking water customers to “use only what you need.” The cheeky ads often featured tangible ways to cut water usage, like one reading, “Grass is dumb. Water for two minutes or less. Your lawn won’t notice.”

Mike Sukle, the firm’s founder and chief creative officer, said the Denver Water campaign was a resounding success. Between 2001 and 2016, the utility claims customers dropped their water usage by 20 percent despite a 15 percent increase in population. (That also was a result of changes to water pricing, usage rules, appliance efficiency and more.)

Sukle said the experience taught him a key lesson: “We don't just tell them what to do. We help give them things to do.”

Behavioral psychologists have shown social comparison is the most effective way to encourage individuals to adopt a more sustainable lifestyle. If you want someone to install LED lightbulbs or solar panels, for example, tell them their neighbors already did it.

Sukle said Denver’s campaign aims to take advantage of the insight. It encourages residents to take small climate actions because those steps could set a social expectation for everyone else. Individuals who do something, in other words, are also more likely to encourage others to do something.

Sukle said that’s why the campaign offers easy ways to participate. His firm has already worked with Goodwill to create a line of used clothes branded with the campaign’s key messages. It also has three branded pedicabs set to offer free rides outside sports stadiums this summer and plans to work with a local ice cream shop to launch a climate-friendly ice cream flavor.

“It's a way to make this top of mind for people. If people don't consciously think about their actions every day, and whether they help the climate or hurt the climate, they don't change their behaviors,” Sukle said.