Updated at 10:16 a.m. on Friday, Nov. 7, 2025

Mayor Mike Coffman and nonprofit and state brass gathered Thursday morning to cut the ribbon on the latest Colorado-grown attempt at creating a “national model” for addressing homelessness.

The project, dubbed the Aurora Regional Navigation Campus, is a 600-bed shelter at the former Crowne Plaza Hotel, a former convention center at Chambers Road and 40th Avenue. Beds will be open starting Nov. 17.

Aurora’s solution to homelessness is very different from Denver Mayor Mike Johnston’s, one that is inspired by the federal government’s longtime commitment to “housing first”.

While Denver provides hotel rooms to people experiencing homelessness with zero strings attached, Aurora will require people to work, be sober and pay 30 percent of their income to the program to stay in individual rooms at the shelter.

Instead of being largely government-funded like Denver’s, Coffman touted Aurora’s program as a “public-private partnership.”

“Aurora will dedicate $2 million a year for security and maintenance of the facility, but everything else is pretty much raised by the private sector,” Coffman told Denverite.

Gov. Jared Polis has celebrated Coffman’s efforts and claimed they appeared more promising than Johnston’s — even though the model has still not been put to the test.

The shelter operator, Advance Pathways, has to raise 75 percent of the funding for the annual budget. If it fails to do so, the nonprofit would have to cut services or possibly lose the contract.

The purchase of the Crowne Plaza Hotel cost $40 million and was funded by the state, Aurora’s American Rescue Plan Act dollars, the federal government, and Adams, Arapahoe and Douglas counties.

The city’s goal is to keep all the spaces clean and safe — two of the biggest reasons people experiencing homelessness cite for staying outdoors over a shelter.

How will the shelter work?

The facility includes a day shelter and three tiers of overnight shelter for individuals experiencing homelessness.

The more sober guests are and the harder they work, the better digs they get.

Each tier in the shelter is designed to incentivize people to upgrade their lives and ultimately establish self-sufficiency, Coffman said.

To enter the shelter, guests have to go through metal detectors, surrender any weapons and drugs and move in for the night.

The lobby serves as the day shelter and nonprofits will connect with clients there.

At the tier one overnight shelter, sprawling open rooms have hundreds of Army-style cots for people to sleep on. There are neither expectations of sobriety nor employment to stay there — as long as guests obey the shelter rules and don’t engage in violence, they can stay as long as they need.

These guests receive a cold breakfast and lunch and a hot dinner. They have the chance to connect with nonprofit caseworkers from various groups around the metro.

For guests who are committed to job training and are working with a case worker, they can stay in tier two semi-private individual beds with shelves. They also get access to a locker where they can keep their belongings, an electrical outlet for charging devices and shelves.

Those guests receive three hot meals a day and some workforce training to be janitors, cooks and landscapers. One staffer described the second tier as bunking like “a minimum-security prison” — except you can leave.

Guests who work jobs and maintain sobriety can move into the third tier, the nicest option the campus offers: upstairs hotel rooms. They’re allowed to stay there for two years. Those guests have to work and pay a third of their monthly salary to the program. That’s typically $1,000 for a minimum wage worker.

Some studio apartments in Aurora cost less than those rooms, giving guests a compelling reason to move toward self-sufficiency.

'Homeless Mike' opens his shelter

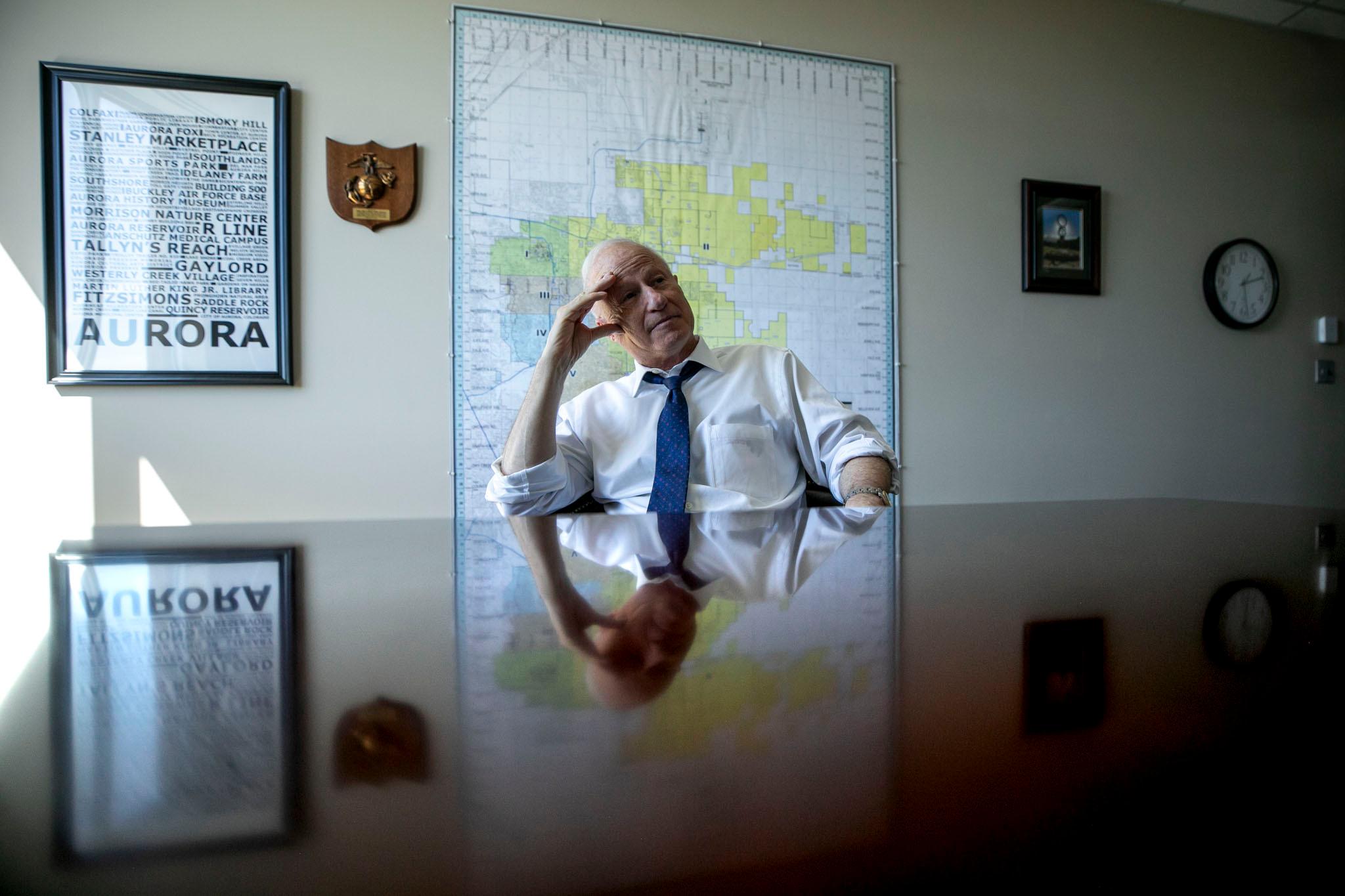

During the pandemic, Coffman lived undercover for a week as a person experiencing homelessness. Taking on the role of “Homeless Mike,” his hope was to better understand why people lived outside.

From his perspective, unsheltered homelessness is a direct product of untreated addiction and mental health problems.

Coffman believes neither the “housing first” nor “work first” models, often viewed as politically polar opposites, are successful for everybody on their own.

Aurora’s shelter mixes what he sees as the best of both. People are incentivized to take more responsibility if they want better food and better living conditions. But nobody has to live outside.

Federal matters

President Donald Trump recently attacked housing first policies via an executive order. The move suggested the federal government would quit funding programs like Denver’s and might consider funding Aurora’s.

Coffman said he has been in conversations with the administration about the new project and is optimistic about collaborations.

The secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Scott Turner, planned to attend the Aurora ribbon-cutting. But with the federal government shut down, he canceled his appearance.

Editor's note: This story has been corrected to reflect that sobriety is not a condition for staying in Tier 2 shelter.