On an unseasonably warm morning in November, Denver Mayor Mike Johnston gathered reporters and city leaders to celebrate a tree.

The sapling — a deciduous tulip tree known for its yellow spring flowers — sat in a shallow hole dug into Benedict Fountain Park, an oasis of green turf nestled against downtown skyscrapers. By burying its roots, Johnston declared the city had met a goal that his administration set the previous January: planting 4,500 trees in 2025.

Denver typically plants closer to 2,500 trees annually, according to the city’s forestry department. By accelerating the pace, at least for a year, Johnston said the city had shown its commitment to guarding residents against rising global temperatures, despite its recent budget struggles.

“Every tree planted is a new location of shade,” Johnston said. “It’s a new, wonderful place for someone to sit on a Saturday morning, or take someone on a date, or propose.”

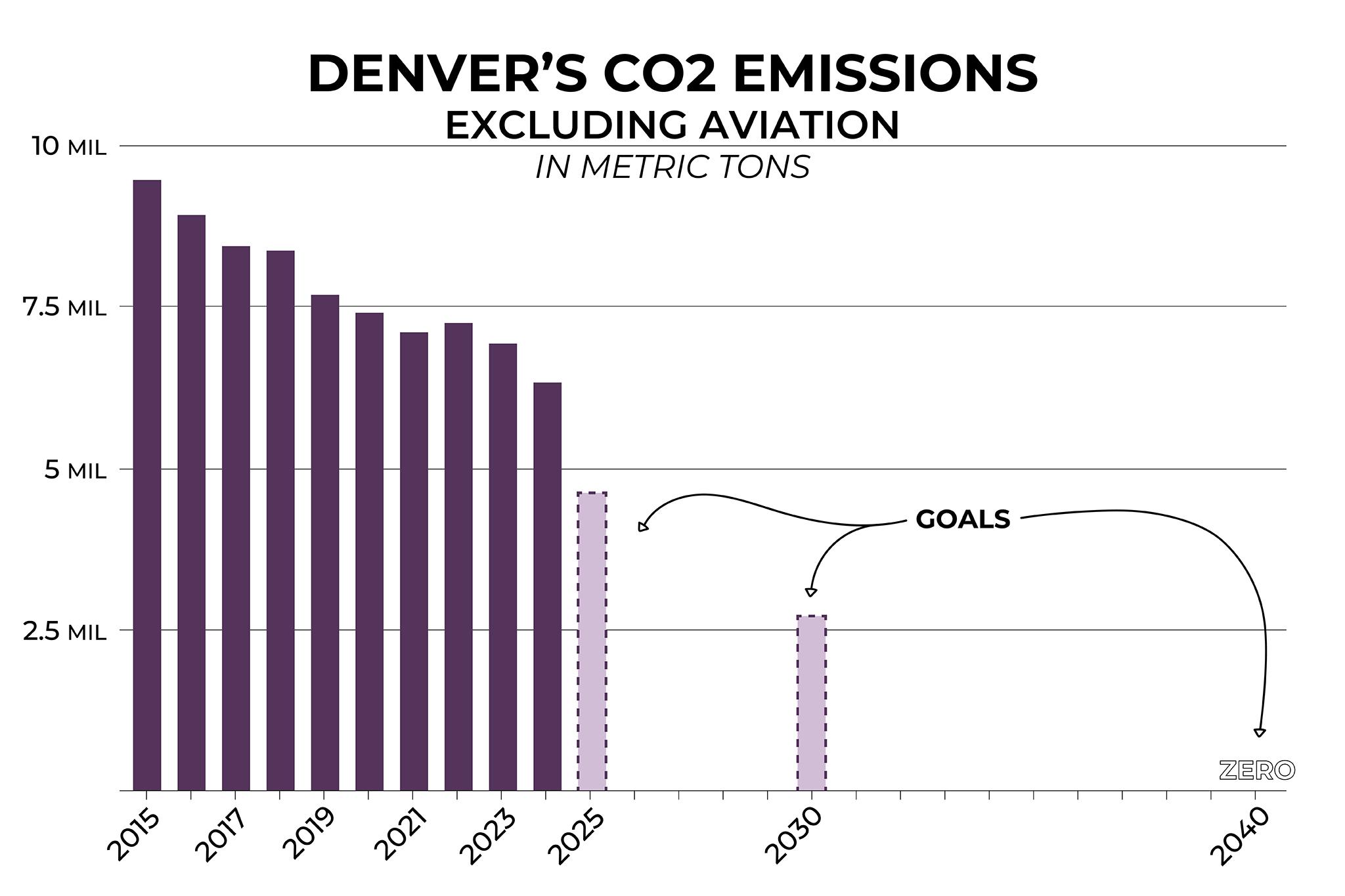

The successful tree-planting sprint, however, comes as Denver sets to miss a major climate target. By 2025, the city planned to cut its planet-warming emissions 40 percent below 2019 levels, a milestone toward completely eliminating any contribution to global warming by 2040.

Johnston admits Denver isn't close to meeting the benchmark.

While the city hasn't finalized emissions estimates for 2025, the preliminary 2024 total was only 18 percent below 2019 levels, and it's highly unlikely the city can close the gap in a single year. Emissions have also barely budged since 2020, when voters passed a climate tax worth 25 cents per $100 of sales within the city.

Voters approved the funding at a time when left-leaning cities embraced climate action to push back against the first Trump administration. Denver now faces the question of whether to redouble its efforts. Amid another federal blitz to roll back climate policies and preserve fossil fuels, should a mid-sized, car-centric city keep trying to erase its climate impact, even if polls show residents worry far more about homelessness and affordable housing?

In an exclusive interview with Denverite, Johnston — a self-described “pro-business, pro-climate” mayor — insisted Denver isn’t giving up on its aggressive climate goals. In fact, his administration aims to publish an updated five-year plan next year detailing how it will hit the city’s next rapidly approaching benchmark: a 65 percent reduction by 2030.

“We're adjusting to try to catch up,” Johnston said on Dec. 3. “And that still will be a very tall order.”

Critics, however, fear Johnston’s track record shows he isn’t ready to follow through. After more than two years in office, many transit and environmental advocates see a mayor willing to plant trees, but reluctant to adopt a comprehensive climate strategy that might upset local business interests or automobile drivers. The city also eliminated nearly 30 percent of the jobs it planned for — but hadn’t necessarily hired — in its climate office amid recent budget cuts.

Others wonder whether Denver should drop its emission goals altogether. Without federal support, it might be smarter for the city to focus on guarding residents against the ravages of living on a hotter planet, said Jerry Tinianow, Denver’s director of sustainability under former Mayor Michael Hancock.

“It really pains me to say, but we probably need to shift over to resilience and adaptation,” Tinianow said. “Because we're not going to make it.”

Denver’s climate goals were always a stretch

The Mile High City wouldn’t have its goals without an earlier citizen-led ballot push.

In 2019, Resilient Denver, a local advocacy group, proposed a ballot initiative to levy a new tax on electricity and natural gas usage. By mirroring a similar approach in Boulder, the grassroots organization hoped to create a new revenue source for climate projects by taxing activities behind greenhouse gases.

The concept, however, faced opposition from former Mayor Hancock and Xcel Energy, Denver’s gas and electricity utility. To arrive at a compromise, the city supported the formation of a task force composed of the city’s leading environmental activists and business leaders.

After months of debate, the task force recommended a sales tax in lieu of an energy usage tax. It also pushed the city to adopt aggressive climate targets aligned with the Paris Climate Accords, an international agreement aimed at limiting global heating to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Denver embraced the compromise by creating a new Office of Climate, Action, Sustainability and Resiliency (CASR). It also referred the sales tax to the upcoming November ballot.

On Election Day 2020, the initiative won in a landslide. Denver was only the second U.S. city in the country to enact a taxpayer-supported fund dedicated to climate action, after Portland, Oregon. The sales tax now generates around $50 million annually — money the city spends on everything from its popular e-bike rebates to new community solar installations.

A year later, the newly formed climate office released a five-year plan adopting the task force’s emissions benchmarks as Denver’s official climate goals.

Elizabeth Babcock, the current executive director of CASR, said those targets were always meant to serve as an aspirational measuring stick, not a realistic policy goal. After all, other climate-minded U.S cities — like Portland and San Francisco — aim to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, a full decade after Denver.

“The goal was really not set based on what's pragmatic or what's possible, but really what does the science tell us we need to do to avoid the worst impacts of climate change?” Babcock told Denverite in an interview in late November. “We take that seriously.”

But at least one member of the original task force has a different view. Sebastian Andrews, who served on the panel as a high school senior at Denver School of the Arts, said participants knew it would be tough for Denver to meet the 2025 emissions goal. That’s why its final report recommended the city find additional revenue to spend $200 million annually to cut emissions, mostly on projects to rebuild streets to favor bikes and transit.

“The bottom line is Denver agreed to cut its emissions by 40 percent, and it's missing that mark mostly because of the money problem,” Andrews said.

Denver’s hot e-bike summer

While advocates pushed a massive investment in climate-friendly infrastructure, the new climate office centered its work around another approach: consumer rebates.

On Earth Day 2022, the city launched steep discounts on home solar panels, battery storage systems, heat pumps and EV chargers — plus discounts worth up to $1,200 for a new electric bicycle.

All of those discounts attracted applications from Denver residents. Only the e-bike incentives set off a summer craze across the pandemic-rattled city.

Applicants snatched up monthly batches of new rebates within minutes of their release online. Bike shops struggled to keep up with demand. Multiple national outlets covered the program as more than 4,700 Denverites took advantage of the program in 2022. Other cities soon followed Denver’s lead with their own e-bike rebates, and Colorado established statewide e-bike discounts to build on the success of its capital city.

Tinianow, Denver’s former sustainability director, watched the fanfare from the sidelines in his new role as an environmental consultant. He worried e-bike rebates might generate positive press, but didn’t necessarily guarantee results.

“Whenever you give money away, it's going to be popular. But the question in climate action isn't whether it's popular. It's whether it's having any effect,” Tinianow said.

Surveys of e-bike rebate recipients show many used their new battery-powered wheels to replace car trips. At the same time, only six percent of Denverites commute by bike, far below the city’s target of 20 percent. Denver’s transportation emissions also remain stubbornly consistent despite the program’s popularity.

It’s a result many of the leading cycling advocates expected. Jill Locantore, the executive director of the Denver Streets Partnership, said the discounts encouraged thousands of residents to give biking a shot. In the process, many realized it’s not always pleasant or safe to pedal around a sprawling city.

Locantore thinks more Denverites now support improved bike lanes and other street safety projects as a result. But she’s still waiting for city leaders to fully embrace their existing plans to rapidly expand the city’s bike network.

“It’s that ‘part two’ of building better bike lanes where perhaps the city is falling short,” Locantore said.

A nation-leading buildings policy

Along with its popular e-bike program, Denver’s climate office also turned its attention to the city’s largest source of climate-warming emissions: buildings.

Denver estimates that commercial and multi-family buildings account for nearly half the city’s total greenhouse gas emissions. By requiring a transition to electricity, the city could take full advantage of growing supplies of wind and solar installed by Xcel Energy, which is committed to shifting to 100 percent clean energy by 2050.

In 2021, the city council approved Energize Denver, a set of regulations with strict deadlines designed to cut energy usage in large buildings over 25,000 square feet. The next year, it approved building codes to phase out natural gas furnaces and water heaters in commercial buildings, beginning with a ban on the equipment in new construction starting in 2024.

It paired the strict rules with incentives to help building owners adapt to the regulations, which has helped the city earn national recognition. A 2024 scorecard published by the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, an environmental policy think tank, ranked the city second for local climate policy nationwide, only behind San Francisco.

The approach, however, has also drawn a pair of federal lawsuits from national and state-level business groups, claiming the construction standards violate a law giving the federal government sole authority to set efficiency standards for appliances.

Denver’s constellation of climate policies — from e-bike rebates to furnace bans — came into focus as former Mayor Hancock set to end his 12-year tenure due to term limits. Any successor could decide whether to embrace the city’s approach or set a new course for the city’s climate funding.

A 'pro-business, pro-climate' mayor

A former state senator, Johnston entered the mayor’s race in 2022 with a campaign focused on homelessness and housing affordability.

Johnston, however, leveraged climate change to separate himself from his main opponent, Kelly Brough, the former executive director of the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce, known for defending the oil and gas industry in TV ads and statehouse hearings.

In his campaign platform, Johnston committed to meeting Denver’s 2040 goal for net-zero emissions. It promised to reach the target by expanding protected bike lanes, working with RTD to make bus routes more reliable, only purchasing EVs for the city fleet by 2025 and ending natural gas in new residential construction, not only commercial buildings.

Today, Johnston acknowledges the city hasn’t met those goals, but it’s managed to make progress despite President Trump’s return to the White House.

“We're fighting massive headwinds at the federal level right now with an administration that is stepping back on a lot of the aggressive commitments on climate that helped us on things like tax credits,” Johnston told Denverite. “But we're not stepping back or slowing down.”

The mayor, however, has been willing to compromise on some of the city’s marquee climate policies. In March 2025, he loosened deadlines and financial penalties under Energize Denver, a policy meant to eliminate 80 percent of climate-warming emissions from buildings larger than 25,000 square feet by 2030. The decision came after building owners and property managers complained that the standards added extra hardship at a time when they were already struggling with rising costs and high vacancy rates.

In addition, Johnston has continued to allow city departments to continue buying gas- and diesel-powered vehicles. While the city is piloting a handful of EV trash trucks and police cars, Johnston said many tasks still require an internal combustion engine.

“The challenge for police vehicles is about the ability to use what are called pit maneuvers, which is if you have to literally t-bone a car to stop it from driving,” Johnston said. “Currently, vehicles that have engines in the front of the vehicle are used to provide the weight.”

The mayor also said the city can’t pursue a ban on gas heating in new homes until it resolves the federal lawsuits over its commercial building rules.

All of the explanations frustrate Ean Thomas Tafoya, a former Denver mayoral candidate and a vice president for GreenLatinos, an environmental justice advocacy group.

While Tafoya endorsed Johnston in the mayoral runoff against Brough, he said the administration often favors private business and development over the city’s climate commitments. He now expects there’s little chance the city will reach its 2030 climate target.

“That happens when you have a mayor who says ‘We are going to be bold and push as hard as we can,’” Tafoya said. “Instead, we have a mayor who says ‘Let’s dial it back.’”

Tafoya can quickly riddle examples. He wishes the mayor hadn’t relaxed Denver’s building policies. He partially blames him for delaying and opening carve-outs to Waste No More, a pro-composting ballot initiative widely approved by voters in 2022. And he’s frustrated by the administration’s repeated decision to scale back bike and pedestrian projects, like a plan to remove car lanes and widen sidewalks along Alameda Avenue.

“Denver has gone in the wrong direction, I think, for most of us in the environmental space," Tafoya said.

The next chapter for Denver’s climate

Carbon emissions are a somewhat simpler problem within the confines of a city like Denver.

States or countries must consider emissions related to everything from farms to oil and gas wells. Denver, on the other hand, has a more straightforward path toward shrinking its climate footprint. Since Xcel Energy is already shifting to renewables, the city can make its economy far more climate-friendly by ensuring its two largest emissions sources — vehicles and buildings — run on growing supplies of clean electricity.

Babcock, CASR’s executive director, said the city plans to continue to focus on those two sectors in its upcoming five-year plan. It’s exploring ways to showcase the best ways to transition large, downtown buildings away from fossil fuels, and plans to explore idea to further streamline the city permitting process to boost all-electric heat pump adoption.

Transportation is a particularly vexing problem. Boulder has seen a significant decline in its climate-warming emissions over the last five years, largely due to rising EV adoption and a reduction in miles driven within the city. With fewer people taking transit since the COVID-19 pandemic, Babcock said the same dynamic hasn’t played out in Denver.

“We are all committed to finding ways to improve transit because it's an essential piece of how we're meeting our goals and improving quality of life,” Babcock said.

In addition, Babcock rejects any assertion that Denver should choose between cutting emissions and guarding residents against climate change. With its climate funding, she said the city can look for projects that achieve both goals at once, like pairing solar with batteries to power homes during blackouts.

Tafoya agrees the distinction between climate mitigation and adaptation is a false choice. At the same time, one project in particular makes him doubt Johnston is committed to either strategy: the Broncos’ plans for a new stadium.

The team plans to build a new arena at Burnham Yard, a defunct railyard a mile south of its longtime stadium site. Johnston claims the project will lure transit-oriented development to an area adjacent to a light rail line.

Tafoya, on the other hand, says the team's current site already sits next to two train stations, and demolishing a 24-year-old stadium to build a new facility will inevitably produce waste and carbon emissions. He also worries the new site along the South Platte River will be particularly vulnerable to climate-driven floods.

“We have to be approaching all of these decisions from a mindset of sustainability,” Tafoya said. “I just can't echo enough about how all these stadiums are going to emit so much greenhouse gases from destruction and construction.”