Denverite reader Sami Powers has spent most of her life in this city. But it wasn’t until recently that she noticed a building that existed here long before she was born: A rickety old barn off Peña Boulevard, on the way to the airport, still emblazoned with red paint.

“What is the red house/barn that is being protected (for historic reasons?) on Pena Blvd?” she wrote to us.

We did some digging to find out.

P.S.: You can ask us questions, too!

The barn is not a landmark, but it is old.

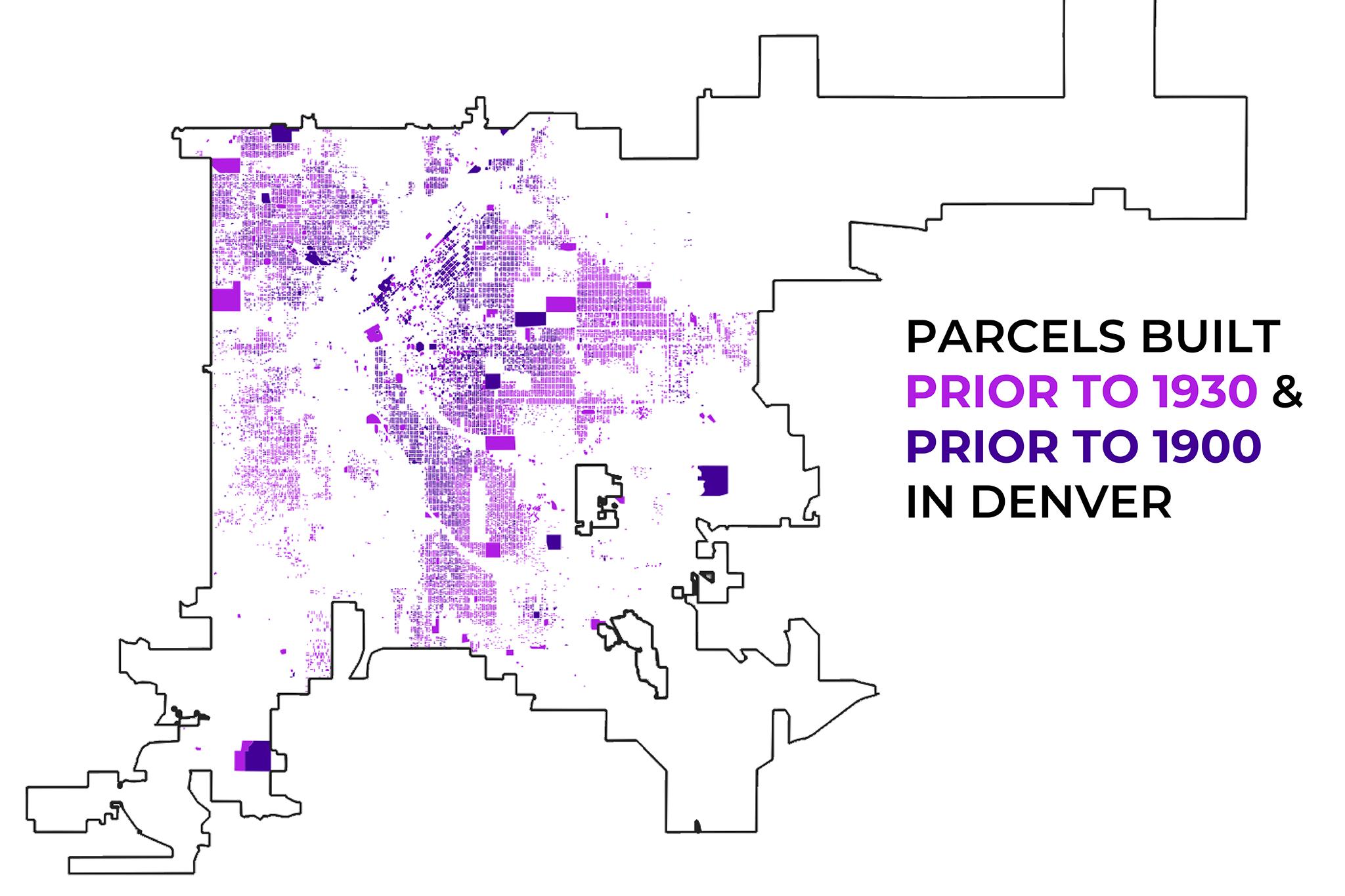

There are 450 official Historic Districts and Landmarks listed on the city’s website, but the old barn is not among them. All of Denver’s existing landmarks are clustered in the center of town, nowhere near the airport.

In 2023, 9News’ Jeremy Jojola wrote that the building was constructed sometime before 1930. He also managed to track down the family that lived there.

We were unable to get a hold of Ed, Don and Debbie Race, who shared their experiences living on the property as children in the 1950s. They told Jojola their parents worked as sharecroppers on the land. They remembered working in the fields surrounding the barn as little kids, driving tractors, feeding livestock, running through the fields and jumping into haystacks. They attended a one-room schoolhouse nearby, and said their closest neighbor lived on another small farm two miles away.

The Race family was forced to move in the 1980s when Peña Boulevard was constructed just steps away from their barn, before Denver International Airport’s iconic tents popped up on the horizon. Their father, Dean, was apparently not happy about the situation. They told Jojola they weren’t sure why the building survived that era.

Denver does have other examples of homes left over after neighborhoods were cleared by construction projects. The National Western Center, which took homes through eminent domain for its ongoing expansion project, also saved the home of a family who still lives in the area.

Denver annexed the oddly shaped airport panhandle from Adams County in 1988. A spokesperson for Denver International Airport said DIA has owned that land ever since. She added it’s surrounded by barbed wire because the building could be dangerous to explore.

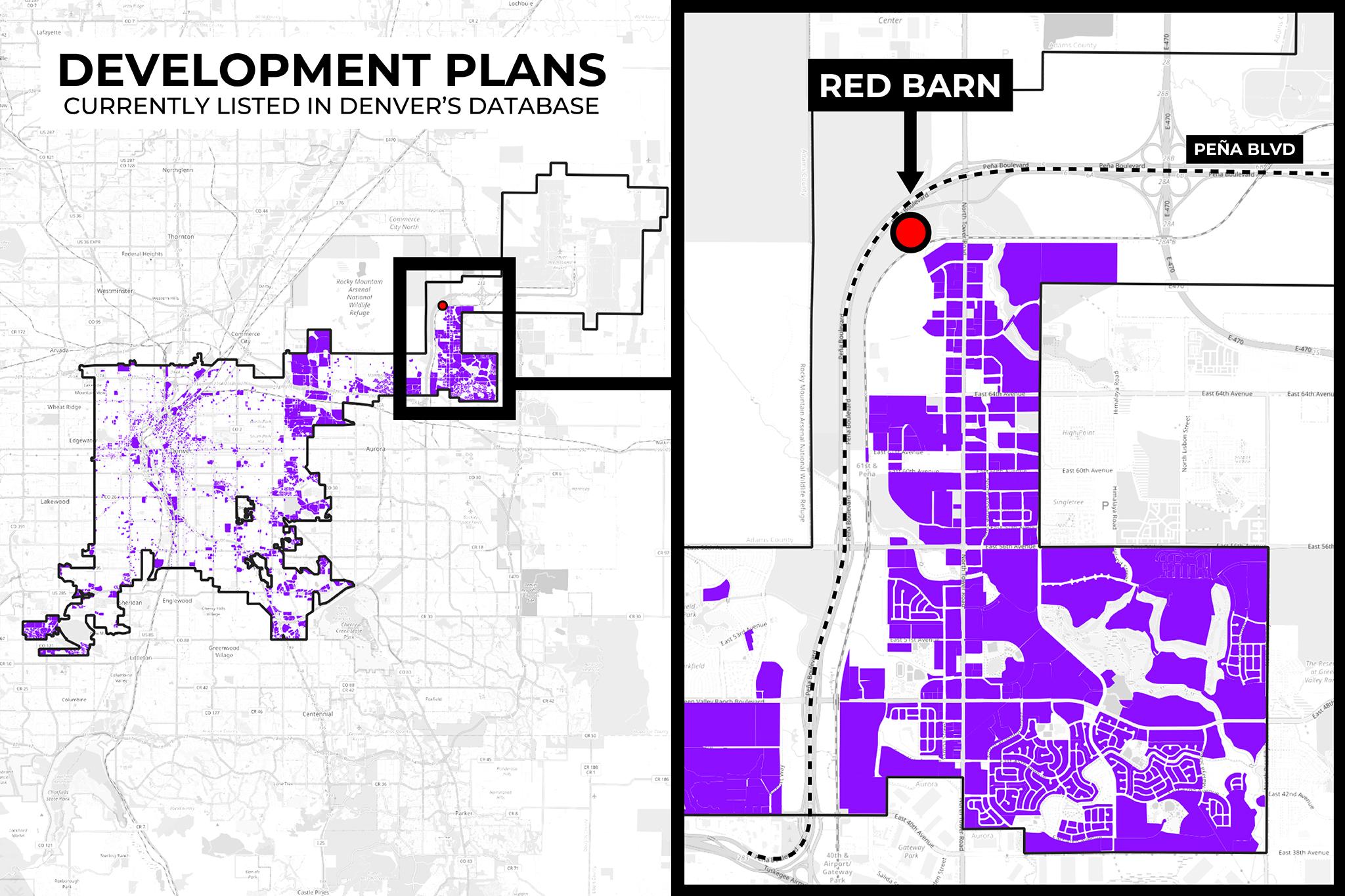

Development is creeping closer to DIA, but there’s no sign the barn is going anywhere soon.

There’s been a lot of talk this year about activating the old farmlands around the airport.

In August, city leaders floated studying what it would take to install a mini nuclear power station in the area, saying it could turn Denver into the “Silicon Valley of nuclear technology” and attract investment nearby.

The former owners of the Park Hill Golf Course entered talks to acquire city-owned land near the airport in exchange for the green space (the final deal still isn’t complete, but the golf course is now in the city’s hands). Coca-Cola was planning to build a bottling plant on 4 million square feet of DIA land, though the company recently announced it would build in Colorado Springs instead. Pepsi is building its own plant in the area.

The city’s development map shows plans for hotels, housing, retail and a flight training facility along Tower Road, creeping up behind the Race family’s old barn. But squeezed in between RTD rail lines and busy Peña Boulevard, there’s nothing on the map that might suggest the little red building is set for demolition.

Sami Powers hopes Denver never knocks it down.

She’s a third-generation Denverite, so local history matters for her. She’s also a planner and archaeologist — she used to do underwater archaeology for the National Park Service — so she sees places like this with a particular point of view.

Communities need shared history, she said, and preservation enables those stories to live on as landscapes change.

It’s especially true in Denver, she added, because the does not have the best track record with preserving its past. She said it was a “travesty” that developers and city leaders allowed so much of downtown’s historic architecture to be razed in the mid-1900s to make room for new builds and parking lots.

“It’s really important that properties like this are saved,” she told us.

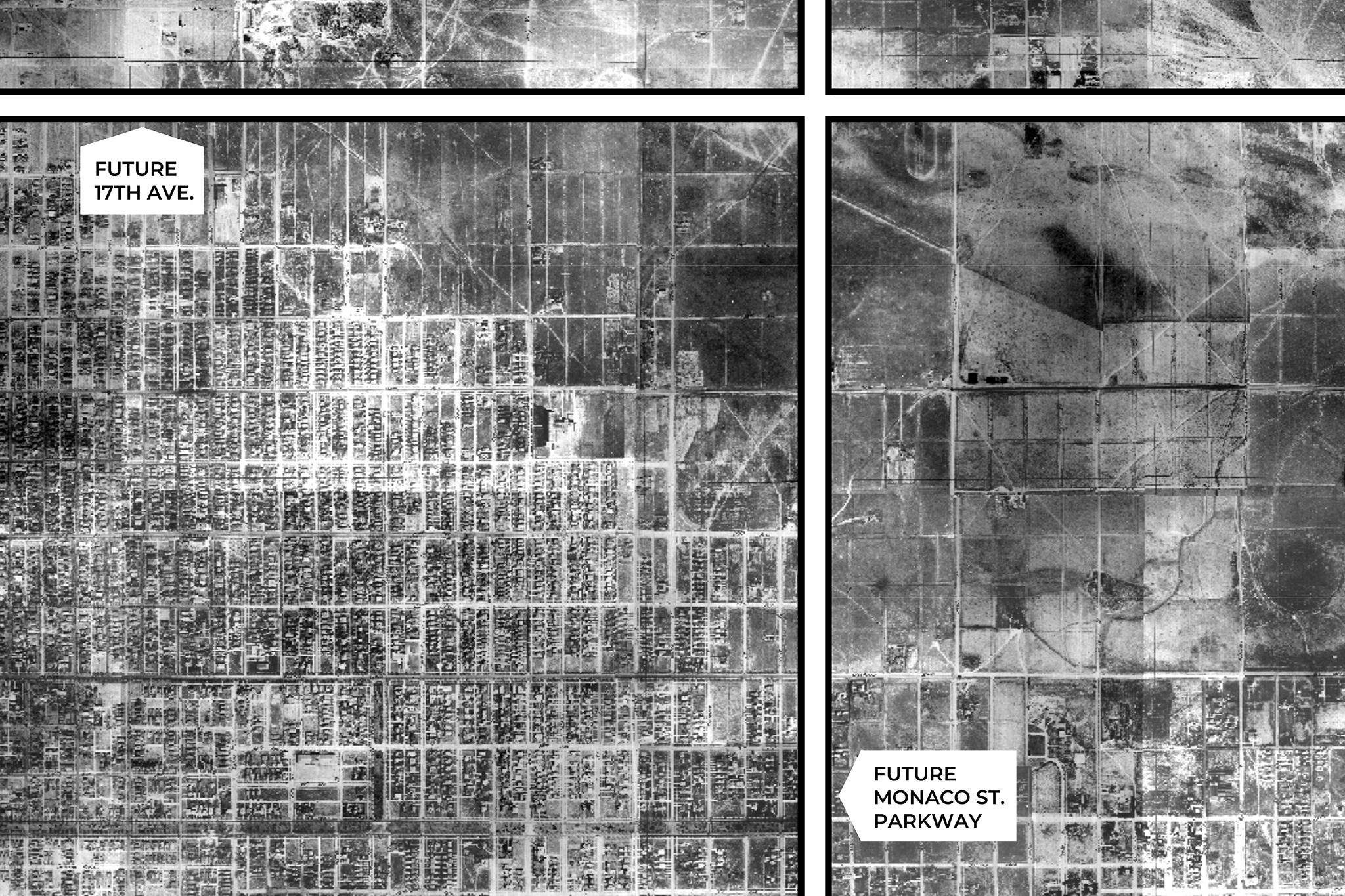

The city’s agricultural footprint has become harder to spot, which could be an argument to save the red barn, should that conversation ever arise. Historic maps of the city show that much of east Denver was still farmland by 1933, when the Race family was likely still settling into their home further out of town. Those properties would become residential blocks of Park Hill and Central Park.

The High Line Canal and the old City Ditch in Washington Park are channels that once carried water to crops, structural relics that you can still visit.

And though Denver has lost some major landmarks, it is still flush with living history. The city’s public real estate dataset suggests there are over 50,000 properties built prior to 1930 that are still standing, mostly residences clustered in central and northwest Denver.