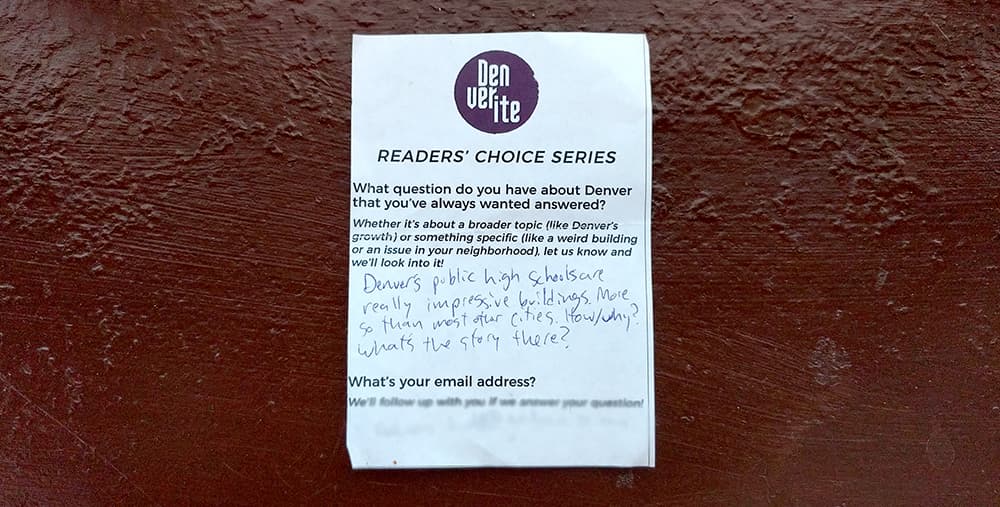

Why are some of Denver's high schools so darn elaborate? That's the question posed to us recently by reader Aaron Hohle, and an appropriate Readers' Choice for the start of the fall semester.

The city's four "compass schools" -- North, South, East and West -- are remnants of the City Beautiful movement that defined so many of Denver's iconic civic buildings. But South High School, in particular, sticks out as a very odd structure. Its facade is packed with detailed scenes of severed heads, beasts and symbols playing out eternal epic battles. These grotesque images, it turns out, are tied to many more landmarks in the city's architectural history, a collection that demonstrates Denver's legacy of odd design.

Denver saw massive growth in the 1920s as the city sought to transform its reputation from cow town to western metropolis. During that time, Denver Public Schools embarked on a $12 million expansion program that oversaw the construction of five high schools, 10 middle schools and 24 elementary schools.

But the push was more than an attempt to provide education. Like designs underpinning the Brown Palace and Civic Center Park, Denver's schools were molded in European styles that were meant to show the city's sophistication. Sites were strategically chosen near parks and at neighborhood crossroads so they could be used and appreciated by the greater community.

"They used prominent architects of the time to lend an air of permanence and fashion to the school system," local historian Shawn Snow told Denverite. The construction projects, he said, came on the heels of the city and county's consolidation, which also merged all of the local school districts.

South, in particular, was destined to become such a lasting symbol. Its detailed figures were designed by Robert Garrison, the prolific Denver sculptor whose work can be seen all over the city.

Like the lions in front of the Colorado Department of Education on Colfax Avenue, the kids on seals in Civic Center Park and gargoyles atop the Midland Savings building on 17th Street, Garrison's work was often defined by his Romanesque style. The Park Hill Library contains a frieze of the Ancient Mariner that one 1920s-era account described as "bizarre, weird and uncanny." Garrison was also responsible for a naked colossus that almost straddled the Moffat Tunnel.

Indeed, what seems to be Garrison's odd sense of humor also permeated his work on South High. One scene above the main entrance depicts a griffin eating a snake that's also being eaten by a fanged fish next to a turtle that's being stepped on and nipping a dragon that's biting a horse. The entryway features a medieval-style scene of teachers flanking a most distinguished principal. Below him is an assortment of beasts that the school's official history says "symbolize unscholarly behavior such as rubber-band shooting and gum chewing."

Atop the main entrance is a sentinel griffin known as "Gertie Gargoyle." The school also features a massive clock with zodiac symbols and at least two severed heads beneath the feet of winged lions that are said to symbolize final exams.

There's a lot to gaze at, what Snow calls a "feast for the eyes."

It's these intricacies that really illustrate the motives behind Denver's early leadership, who sought to redefine the fledgeling city with visual distinction that has lasted more than a century. This ethos might have been best expressed in South High's application to become a historic landmark:

"Therefore when we build, let us think that we build forever. Let it not be for present delight, nor for present use alone; let it be such work as our descendants will thank us for, and let us think, as we lay stone on stone, that a time is to come when those stones will be held sacred because our hands have touched them ..."

Curious about Denver? Ask us your own question!