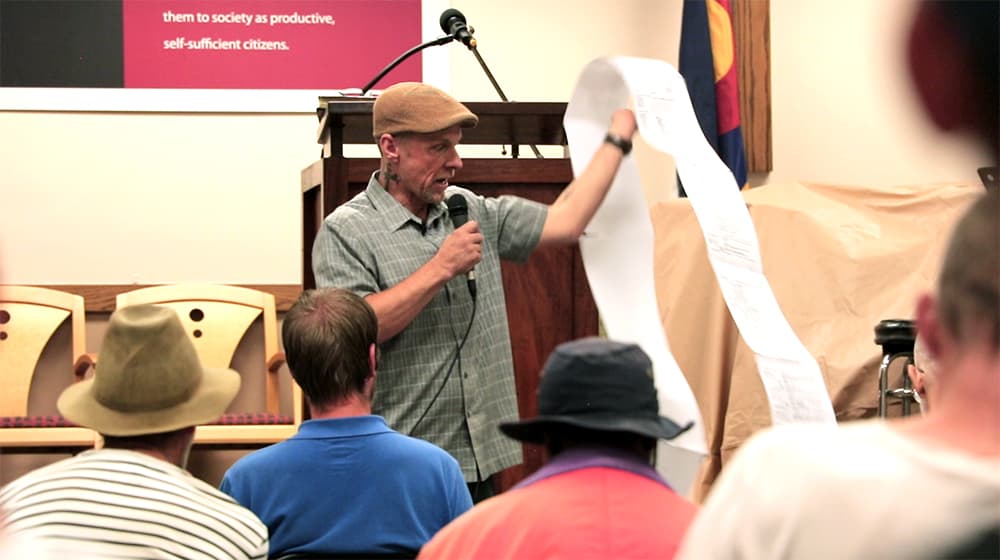

George Medley sometimes subs as a guest preacher at the Denver Rescue Mission. He's a good fit for the job, he says, because he has something in common with the folks who have hit bottom and are attending service as they wait for free food and shelter.

Medley was once homeless himself. He says he was an addict, a drug dealer since he was a kid, on the run from the law under an alias, in and out of jail for years. He tells the crowd he's a testament to how you can turn your life around.

But, he said, giving his life to God and cleaning up didn't mean his troubles were over. He found a very difficult challenge in getting steady work after he tried to turn a new leaf. It's a problem that many ex-cons face; failure could mean turning back to trouble.

Medley started recycling with a pickup truck and a few Craigslist postings, then upgraded to a trailer, then a flatbed. Before long he'd opened Denver Scrap Metal Recycle Center, a sprawling junkyard on North Washington Street with a funky sign out front reading "PRAISE THE LORD."

In charge of his own business, Medley actively works to hire men out of prison. After his sermon at the rescue mission, he told at least two people to find him in Globeville. If they're not ready to give a job a shot, they at least might find something they need at the food bank Medley runs there on Saturdays.

The National Reentry Resource Center reports that less than half of people released from prison in a three-state area of study had secured a job upon their return to the community. Meanwhile, they say, 75 percent of people from prisons in 30 states were arrested within five years of release.

It's easy to see how employers might have a hard time trusting felons, but it seems their unease to hire people out of prison contributes to recidivism.

Medley gave Frank Stahl a shot at a job about three years ago after Stahl spent nearly three decades behind bars. That tension between trust and turning back to crime, Stahl said, is a real threat for some people.

"They look at a felony record and that's all they see," he said. "Not all ex-felons are going to be repeat offenders, as long as they have a good job, a good place to stay: we'll do alright."

After hearing a lot of, "We'll call you," from uninterested employers, Stahl says he's glad Denver Scrap Metal gave him a chance.

As for George Medley, he sees a lot of visual metaphors playing out in his junk yard. He says men, like tossed-aside material, get crushed, organized, shipped out to be ground up and melted down. Once the old and rusty hits a kind of "rock-bottom," he said, a transformation happens. The raw material becomes something shiny and new.

Scrapping takes a kind of foresight, Medley said. Like the men who make it working in his yard, all that rusty metal needed was someone to see value in what others discarded as trash.