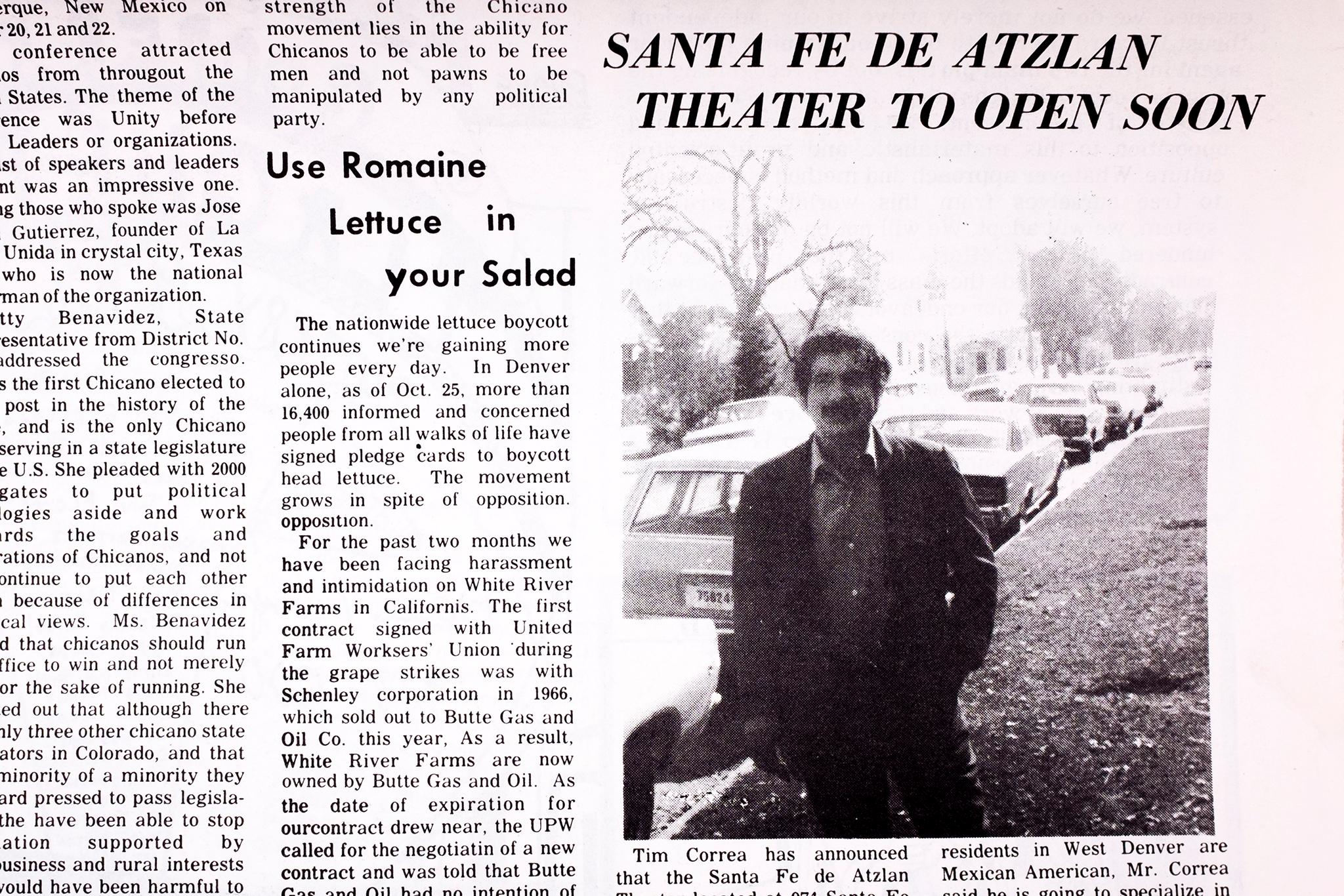

Tim Correa more or less stumbled into owning the Aztlan Theatre. Or more accurately, he stumbled upon the pale facade of the Santa Fe Theater, as it was previously called, while driving across the street that shared its name one day in 1972. It would be months before he would get a chance to finally rename it.

An activist in the Chicano Movement in Denver occasionally involved with Corky Gonzales’ Crusade for Justice, Correa would end up christening the theater Aztlan, after the mythical homeland of the Aztecs, now reclaimed by Chicanos as their own ancestral home.

“Anglos ask what Aztlan means,” Correa said during an interview inside Timeo's Theatre Bar, the gin joint next to the theater. “It’s a situation where Chicanos are free. It’s just like what Martin Luther King was talking about. It’s a mythical kind of thing, in a way. And I think there’s a city or pueblito that might be called Aztlan in Mexico.”

That activist spirit continues to this day. Anyone taking a stroll down Santa Fe Drive will occasionally see politically-charged messages on the theatre's marquee. Some recent examples: "SCREW THE WALL. SPEND $ ON TEXANS. SUPPORT DREAMERS," "CRUZ AND RUBIO ARE ANOTHER TRUMP" and, in November 2016, "STOP TRUMP BY VOTING FOR HILLARY."

The theater is a living remnant. It’s no longer in the same shape that once caught Correa’s eyes so many moons ago, when its facade would have fit nicely along “Theater Row” on Curtis Street during its prime. The outside walls are rugged, and even from a distance, the walls look like they’re in dire need of restoration. Correa tried obtaining historical preservation status for the 900-person theater a few years ago, which would have opened the doors to grant funding, but it didn’t work out.

At this point, he said, he’s just coasting along. After years of potential buyers and conversations about ownership, he’s ready and poised to turn over the reins of his theater. He admits he probably should have sold the place several years ago: “We’re thinking of doing that now. We don’t have no other choice. We want to keep it as an entertainment center; we’d probably put that in a contract.”

In reality, he said, he’s never really been close to selling it, though he’s had a fair share of offers.

He’s ready to sell now for various reasons, though it's his sister Anna Correa’s passing that seems to weigh most heavily on a decision to shift his focus in life away from his theater. He’s already been approached by people who are interested, including “one lady who’s really interested, she fell in love with it.”

“The art [district] has their own thing now, with the galleries and all that,” he said about how the Aztlan’s sale would impact the neighborhood. “And actually, probably, a lot of people have old memories of the movies, because a lot of them live around here, but if I sell to other people that want to do the same thing, then it probably shouldn’t change much of anything. Some of the people who want to buy it have already said they want to bring bands back, the bands that already played here.”

The theatre used to host movies before becoming a haven for rock shows for up-and-coming and underground acts.

The inside of Timeo's Theatre Bar looks like it could be a long, bottle-stacked corner in Correa’s own home.

Behind the bar, there are colorful portraits, paintings, photos of him, his theater and his family, including a photo of his sister. Overlooking a checkered floor with a few tables is a large portrait of Mexican Revolution icon Emiliano Zapata. Across the bar are various posters of some of the Mexican films the theater once screened. It’s a cozy, eclectic space that even on a Thursday afternoon looks ready to host any combination of Chicanos, bikers, hipsters, bohemians and maybe even a city council member or two.

A small corridor connects the bar to the theater’s lobby. Correa walked through and approached an ugly old door. After lifting some clunky chains, Correa walks into his teatro, which usually hosts electronic dance more than rocks shows or films. Correa also rents the place out — opportunities he doesn’t waste (he politely took a call about a potential client during our interview).

Correa’s voice echoed through the hall as he described the scene from a previous weekend show, which he said was a techno music show.

“There was a big splurge in techno music; actually they’re called raves, but you don’t mention raves, because police don’t mention raves, they don’t like that word,” he said near a giant area in front of the stage that once had seats, later removed at the request of performers. “Can you imagine 900 kids over here?”

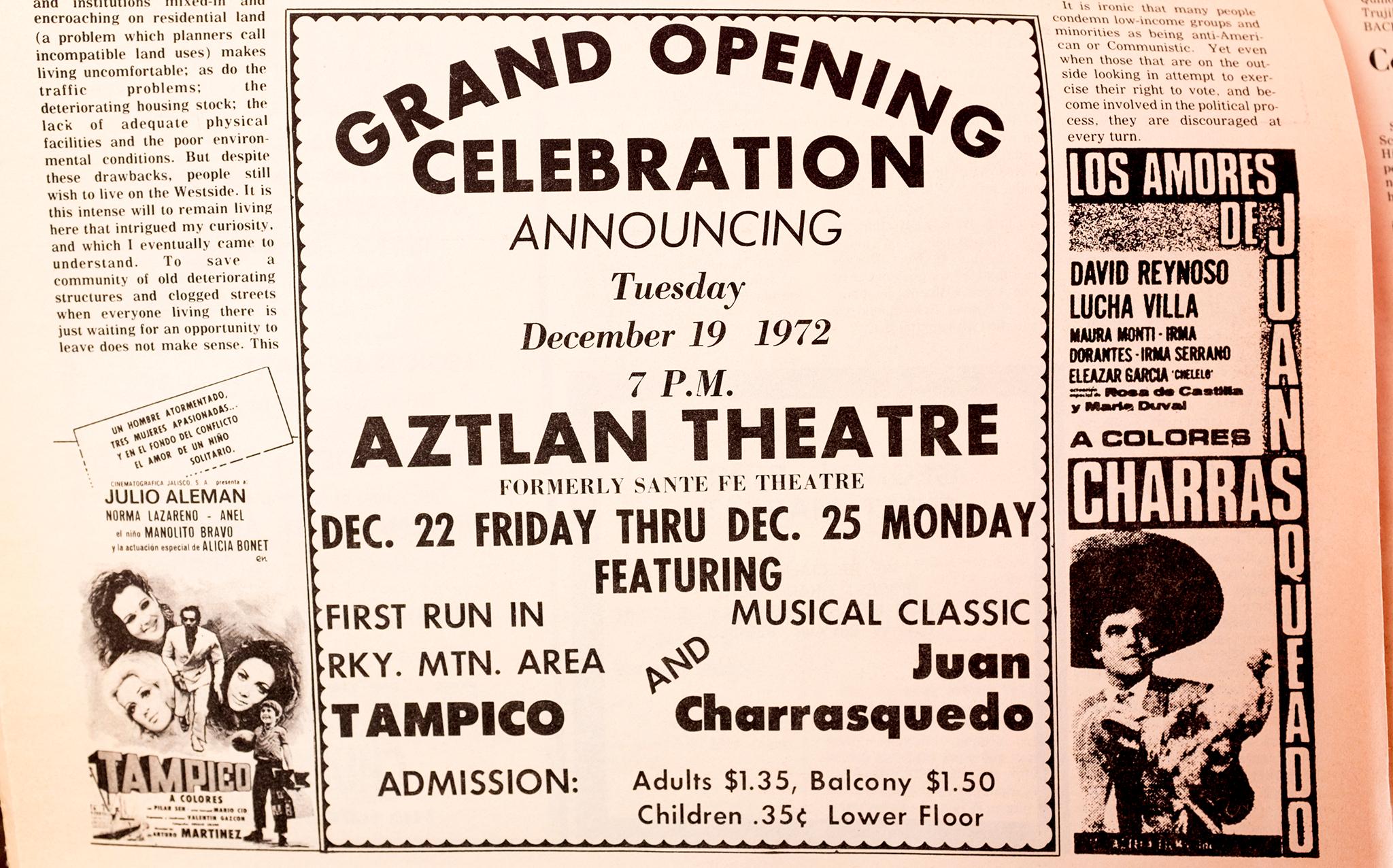

It was probably a different scene during its grand opening celebration in December 1972, during a kick-off Correa said only came to fruition after he and a friend cleaned the place up, gum-plastered rugs and all. An ad for the event in the West Side Recorder showed the celebration would include a first run of "Tampico" and a showing of "Los Amores de Juan Charrasqueado," which was first released in 1968.

“We invited the whole Denver area, the community,” Correa said. “We had burritos, we had all kinds of different horderves, everything. And then, ¿sabes que? The next day we said come on, we’re going to show the movie as — I think we did that on Saturday, tomorrow we’re going to open, Sunday, all day, the movies. Nobody showed up. A la chihuahua!”

As more nearby theaters closed, it left Correa with less competition. At the time, he said it was one of three theaters in the city showing Spanish-language Mexican films.

“We started packing them in here, 800, 900 on a Sunday and a Saturday,” he said. “We were open Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday.” He did for about 13 years until the VCR arrived and started moving eyeballs from the big screen to small screens at home. He struggled to compete with the in-home entertainment, leading him to take a job placement program affiliated with the city that helped find work for Chicanos.

“They lost the sociability of it,” Correa said. “Why did they not come back? Sure, they spent a lot more money. ... A lot of people before met their girlfriends here, the girls met their husbands here. They come back with two kids two or three years later or whatever.”

While he tried figuring out the best way to keep the theater afloat, he was approached by a local promoter who often worked for the Gothic Theatre. He called him and asked him if he could rent his theater for a rock concert in April 1987.

“I said, ‘Oh, what band are you bringing?’ he said, ‘The Red Hot Chilli Peppers.’ And guess what I said? I said, 'Who are they?' I didn’t know who they were. They were coming out of California.”

After that, they hired a booking agent, who started booking bands like AFI, Run DMC, Slayer and Fishbone.

“They’re millionaires now," Correa said. "They’re rich. I made everyone rich except me.”

During the 1960s and 1970s, the theater was a hub for Mexican entertainment.

The original Santa Fe Theater opened in November 1927, according to a Denver Post brief from that year. The theater cost $150,000 and was slated to screen first-run films, with the first photoplay shown at the theater called “Women’s Wares,” a silent film directed by Arthur Gregor. It was built by W.J. Carter and included a full stage for “roadshow attractions,” vaudeville entertainment and projection for movies.

“The exterior is of Spanish motif, and the interior decorations are in harmony,” the Denver Post brief read. “Wide aisles, comfortable spring-cushion seats have been provided from front to back, and no detail has been overlooked that might make for the convenience of patrons.”

It was later closed for some time before it was reopened full-time in 1966 by Abel Gallegos, a professional singer from Mexico who would end up calling Denver home. It's unclear how long the theater had been closed before Gallegos took over.

Gallegos came to the United States during a tour and decided to stay, first settling in Salt Lake City in 1946. It’s there where he met his future wife, Mary. The two visited Denver in 1949 and later decide to move there permanently, according to a profile from the July 1970 edition of the West Side Recorder. The two had three children.

The Gallegos managed the theater with hopes of creating an entertainment center for Mexicans families and westside residents. But they had bigger goals than just screening movies, as they sought to host acting and dancing classes for “Spanish surnamed young people,” since they felt they often didn’t get the opportunity to develop such talents.

The theater screened American and Mexican films. Gallegos tried to figure out what combination of films would bring the best attendance, usually screening more Mexican-made films to ensure community members got a chance to learn about their culture. Admission in 1970 was $1.25 for adults and free admission children with parents. Kids without parents were allowed too, but they had to pay a $0.25 admission fee. And things could get tricky, as Gallegos sought help for managing children who attended the theater alone: He requested parents leaving their kids to leave addresses and phone numbers so they could be contacted “in case of emergencies or misbehavior.”

“It was a really great theater in its heyday. Santa Fe was a great strip in its heyday,” former NEWSED President and CEO and community figure Veronica Barela said recently.

Barela, who's running for City Council, has lived in Denver her entire life. She was born on Denver’s west side and grew up in the North Lincoln Projects, attending local parochial and public schools before graduating from West High School.

Through her work with NEWSED, a community development organization, she’s both witnessed and taken part in the revitalization on Santa Fe Drive.

“Santa Fe Drive had everything on it. You didn’t have to go downtown,” Barela said. “It was a fun neighborhood because everything you had was there.”

The neighborhood included three theaters: the Aztlan, the Cameron Theatre (now Su Teatro Cultural and Performing Arts Center) and a third theater Barela couldn’t remember but said she’s pretty sure now houses a private business.

During the 1950s, Barela said, she would go to the former Santa Fe Theater during weekdays with her older sister, Bella, to watch scary movies featuring mummies and vampires.

“We would walk home back to our house in the projects in the dark,” Barela said. “It was kind of creepy and scary, but it was fun. That’s how I remember the Santa Fe Theater.”

Who might take responsibility for the Aztlan next is unclear — as is Correa's memory of who did it before him.

The theater no longer looks as pretty as Barela once remembers it. She said that along with the former Cameron Theater, the Santa Fe Theater was known for its ornate designs.

“It’s become a real eyesore on Santa Fe Drive,” Barela said. “It’s in real bad shape. Really, really bad shape.”

After Correa took it over, Barela said she tried working with potential buyers interested in theater, including buyers interested in renovating to its original form. None of them materialized, and she soon stepped away from trying to broker deals with possible buyers. She said she hasn’t been involved in any of its possible dealings since the 1980s.

Correa doesn’t remember the name of the guy he bought the theater from back in 1972, only that it was a guy who “used to play horses” and owned other theaters in Denver. (Denverite could not find a property record for 976 Santa Fe Drive through the city's website.) In order to purchase it, he decided to apply for a loan with a partner through the Small Business Administration.

“Around that time, they were talking about Chicanos picking themselves up by their bootstraps and all that, and I say, here I am, I’m a Chicano, I’m trying to buy this theater.” They kept requesting additional paperwork. The entire process lasted about eight months. “I thought that they were just pulling my chain. So they call me back again and they say, ‘Well, Mr. Correa, you know, what do you think?’ I almost turned it down...they say, ‘Can you wait two more days?’”

Sick of the runaround, Correa said he came close to walking away. But when they asked him to wait two more days, he figured it wasn’t much compared to eight months. Two days later, they called him to inform him the loan had been approved. His final price for the theater?

“That’s a Chinese secret,” Correa said, laughing.