Denver Public Health recently released a comprehensive report on depression in Denver that took a deep dive into the state of depression, as well as the status of mental health overall in Denver.

Within that report there were significant examples of overrepresentation in people experiencing depression for certain segments of the population. Some of the groups with the highest rates of depression were pregnant women, men, and LGBTQIA teens.

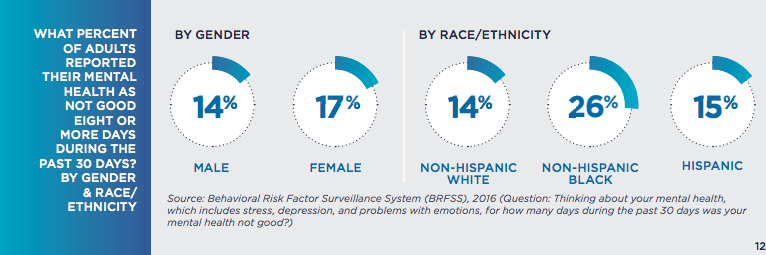

The report also broke down "adults that reported their mental health as not good eight or more days during the past 30 days" by race/ethnicity -- 14 percent for non-Hispanic white folks, 26 percent for non-Hispanic black folks and 15 percent for Hispanic folks.

That 11-percent gap between black residents and other groups is noteworthy but is need of additional context to be properly interpreted.

And while Dr. Bill Burman, executive director at Denver Health, cautioned that those numbers reflect a very small sample size, national statistics still show that there is a persistent gap in the mental health outcomes of the black population in America when compared to other racial groups throughout the country.

Like in every other aspect of life, historical context matters.

"Black people in America tend to have some of the highest rates of chronic stress because of all the things we go through," said Dr. Terri Richardson, vice chair of the Colorado Black Health Collaborative.

She explained that black Denverites are in a unique position, being in a major, urban city that is often described as less diverse than it is and is rapidly becoming increasingly white. She said that the size of the black population in Denver makes it easy for the group to be overlooked.

"We have the same health challenges and face the same discrimination as others in the larger cities. It may not seem as prominent here it in the news, because we're in Colorado," Richardson said.

Tony Young, the former national president of the Association of Black Psychologists and the current president of the Denver-Rocky Mountain Association of Black Psychologists, said to resist the urge to look at this data in a vacuum.

"It's important for Denverites to recognize that all of us do not have the same histories in America and people of African descent by and large did not come to the country as immigrants," he said. "There's this myth of a colorblind society, that we have a level playing field that we've never had."

He said modern-day Denverites can't be absolved from working to confront the legacy of racist policies from the past that created the conditions we currently see.

"We have the same racial history this year as we had 10 years ago, as we had 80 years ago in the city," Young said, pointing out high-profile instances of that history including redlining, the fight over forced school busing, and the rise of the Ku Klux Klan into the city's highest leadership positions.

Establishing mental healthcare equity is about much more than healthcare.

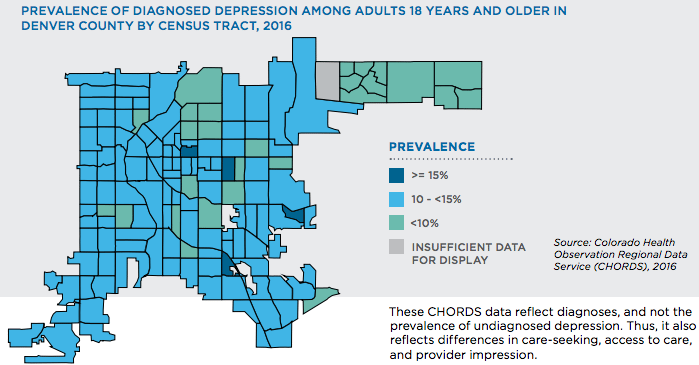

The Denver Health report says that the reasons people experience depression are varied but notes that "social determinants" -- things like environment, income, education and safety -- can play a significant role in mental health outcomes.

"Social determinants?" Richardson asked rhetorically. "Schools have been a mess out there, a few years ago they were trying new models in the school, they have schools with in the schools... the food desert is a major issue, particularly in Montbello."

Rhonda Coleman, a Doctorate of Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine and founder of the now closed Healing Garden, echoed that notion adding that the things that people overlook greatly contribute to someone's mental health outcome. With the Healing Garden, Coleman was looking to reduce gaps she noticed in Denver's residents in the northeast receiving preventative care, with an emphasis on alternative medicinal practices like yoga, and nutritional services. She said even issues like poor transit can weigh heavily on people's mental health situations.

"One of the biggest reasons is that black people as a whole do experience more trauma because we are very communal people," Coleman said. "If you have family in Chicago, if you're hearing something on the news everyday, it's going to impact you as a person. We feel for other black people no matter where they are. There's constant news about black men being gunned down by police."

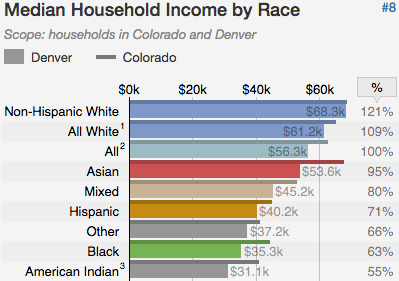

Another huge social determinant that is hard to address and even harder to avoid, according to Coleman, is the impact financial status has on our mental health outcomes.

"Financial resources are often causes of struggles in the black community," Coleman said. "People are working more than one job trying to fill holes left by family members. People experience frustration because of the lack of financial support and financial stability. We live in a capitalistic society it's really hard to not be impacted by money."

According to national data provided by Denver Health, there seems to be a clear relationship between income and mental health outcomes. Recent U.S. Department of Health and Human Services research said that "the prevalence of depression decreased as family income levels increased ... 15.8 percent of adults from families living below the federal poverty level (FPL) had depression." For adults living at or above 4 times the federal poverty line, that percentage dropped to 3.5 percent.

According to U.S. Census data, black Denver households bring in a little more than half of the income that their white neighbors do. The latest Census data shows that non-Hispanic white households bring in just above $68,000 while Denver's black households bring in just above $35,000 a year. Income however, is not the only statistic that displays financial health. According to a 2016 report issued by the Colorado Trust, a health equity foundation, the separations in familial net worth in the State of Colorado along racial lines are even starker than the ones found in income. Those net worths are "$110,637 for white households, $8,985 for Latino households and $7,113 for black households."

That income disparity, in conjunction with the well documented wealth gap, is a recipe for financial hardship for Denver's black families, which as Coleman noted can put a strain on mental health both individually and communally.

Structural issues in mental health services play a large role as well.

Coleman noted that culturally responsive care is currently lacking in the mental health field and that prevents many black residents for seeking care out. Recent research from the Harvard Business Review shows that people were likely to be more receptive of receiving care and receive more comprehensive care from culturally representative doctors.

"So many black people, if they receive any kind of counseling or mental health support, it's from their church, and that's not always ideal," Coleman said. "People feel comfortable because they know their pastors care about them. They're a part of their community."

A disconnect between patient and provider can cause people not to seek services, according to all of the experts interviewed for this story. Specifically, Richardson said, it can be discouraging to someone who doesn't want to have to explain their culture to someone new.

Jason Shankle, founder of Inner Self and Wisdom, put it this way: "When you sit down with someone you're going to be vulnerable with, you're going to want some type of cultural connectedness."

He said there's not a lot of of black people working in the mental healthcare field in the larger institutions so in order to reduce the gap in treatment, black Denverites should support the local black businesses that do that work.

Richardson said that due to the pressures of gentrification, the sense of a larger black community has dissipated in the city. That, she believes, has made it harder for black Denverites to receive support, and that can have an impact on mental health.

"There really used to be a black neighborhood. That's stress for them in that, 'We don't have our neighborhood, we don't have anything, we don't even have one neighborhood'," Richardson said. "We've gotten to a point where we've separated out mental health and physical health but everything is connected, mind, body and soul."

Burman, at Denver Health said he's noticed that he hardly has anyone turn him down when he offers other kinds of health support as a physician because mental health providers are available immediately. He said research shows that people are more likely to receive additional care if they don't have to schedule an additional appointment or head to a different location.

Is there a way to shrink the gap?

Coleman said one of the ways to shrink the gap we see in mental health outcomes involves the black community becoming more self-sufficient in terms of providing support. One example, she said, is the Black Panther Party, who worked to create health clinics in black communities.

"We need a lot more support getting people into mental health and other preventative health positions," she said. "Things that help destress people need to be more accessible to people. We need to be having people from the community provide these services. When you think yoga studio, you think gentrification. You don't go into the hood and find a yoga studio often. All the things that improve mental health status are found in more affluent and gentrified neighborhoods. What are you going to do, go drive into Cherry Creek and get a massage and relax?"

According to Young, Denver is not necessarily doing anything particularly different to produce these racial gaps in mental health. The findings in this report can better be read as a micro showcase of the macro-level systemic problems in the country, he said.

"Denver, Colorado is really no different than just about every other major American city," he said. "It's just that the racism is less overt and because the numbers are smaller they tend to be more readily ignored than in larger cities with larger black populations."