Failure to verify that prospective home buyers would be able to pay their bills was among the missteps and miscalculations outlined in a report from Denver's auditor on the Office of Economic Development's stewardship of the city's affordable housing program.

Now a major builder says OED's fix -- strictly requiring that buyers spend no more than about a third of their income on housing -- has made it too difficult for people who are the intended beneficiaries of the affordable housing program to get homes. And that's hurting his business and the program, said Gene Myers, CEO of Thrive Home Builders.

"We can't go forward under these rules," Myers said.

Britta Fisher said the audit began three days after she started work as the OED's chief housing officer last May, and that she welcomed having extra eyes look at her department's processes as it worked to get people in affordable homes -- "and keep them in them."

"We do want to look at whether we are cost-burdening our homeowners," she said.

Families that spend more than about a third of their income on rents or mortgages and other fees are widely regarded as being stretched dangerously thin, or cost-burdened. Home owners may struggle if a major repair or other unexpected expense crops up. The consequences could be foreclosure if they miss mortgage payments as a result.

Myers's Thrive, which also produces market-rate homes, has since 2007 been building homes reserved for moderate-income families in Stapleton on land and with subsidies provided by developer Forest City. Forest City, which last year was acquired by Brookfield, won the lucrative contract to develop what had been Denver's airport in 1998 and agreed to put 10 percent of the neighborhood's homes in reach of people who can't afford market rates, with covenants to ensure affordability upon resale as well. The 10 percent goal has been elusive even as a widening gap between earnings and home prices in recent years has focused more attention on Denver's housing crisis.

Thrive in 2016 launched its most recent Stapleton product, the Elements Collection of two- and three-bedroom townhomes priced in the low $200,000s. According to the latest Denver Metro Association of Realtors report, the median price for a condo last month was $290,000. Myers said Thrive has sold 93 Elements townhomes since 2016 and that they had been moving at a rate of about six a month. The rate began slowing after the city began strictly applying the 30-percent rule, Myers said. Thrive recorded no Elements sales last month.

When he released his report late last year, Denver Auditor Timothy M. O'Brien said OED had been simply checking that people who wanted into the city's affordable housing program met income limits and had not been verifying that their mortgage and fee and other related payments would be under 30 percent of their income. O'Brien said OED began adhering to the 30-percent standard after his audit began.

City regulations do allow some discretion. Fisher, OED's housing officer, said she and her staff took Denver's "escalated housing market" into consideration as well as practices in other cities when they shifted the standard to 35 percent in January. At a public meeting when the change was being considered, she heard from home buyers who were at 33 or 34 percent who would be able to buy their homes because of the shift. She also heard from housing counselors who work with low- and moderate-income families and who worried that loosening the 30-percent rule would be a mistake.

But Thrive's Myers said even 35 percent was too high a bar. He said his company was able to check with lenders on 44 Elements sales that closed in 2017 and 2018 and determined those buyers' housing costs averaged 39.6 percent of earnings.

When he released his audit, O'Brien said home buyers who were spending more than was advisable faced a higher risk of foreclosure. According to OED, in most cases the covenant restrictions meant to preserve affordability are removed in foreclosures in which the bank or other entity that held the first mortgage acquires the property. OED, which oversees about 1,400 homes in an affordable program, already has a problem with ensuring covenants are preserved. The department acknowledged last year that more than 300 homes slipped out of the program because covenant restrictions on their prices were not adhered to when the original buyers sold them. OED has been working to bring those homes back into compliance.

Home builder Myers said that of the total 212 affordable homes Thrive has sold in Stapleton, only one buyer has gone into foreclosure. Thrive is not the only builder of affordable homes in Denver. According to OED figures, 263 homes in its program have been foreclosed since 2005, most of them between 2008 and 2013, during the height of the recession.

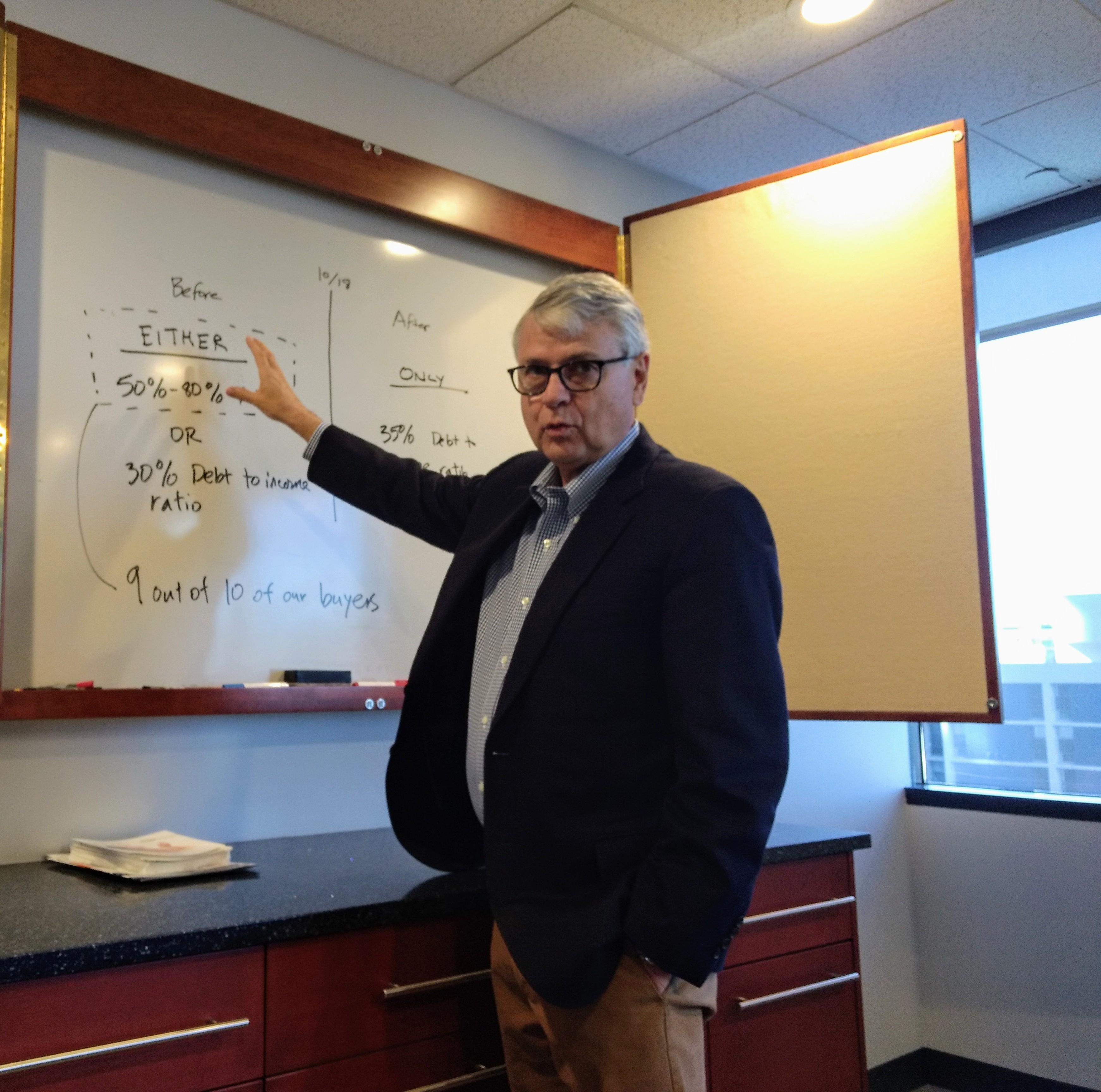

Myers said that as he reads the city's voluminous Inclusionary Housing Ordinance, OED staff members have the option of determining that a prospective buyer is eligible to participate in the affordable housing program based simply on whether they are earning at least 50 percent of the area median income and generally not over 80 percent. Nine of 10 Thrive home buyers were able to enter the program under that rule, Myers said. It is too strict to require that families spend no more than 35 percent of their income on housing, he said, noting that private lenders and the Federal Housing Administration are more lenient.

Myers added that many people trying to buy a home are spending more than 35 percent of their income on rent. Lindsay Wilson falls into that category.

Wilson has been commuting from Colorado Springs since taking a job managing a warehouse for a Denver plastic products manufacturer about two years ago. In that two years he had looked in vain for a house he could afford in Denver until he found Thrive's Elements. Wilson said he was impressed with not only the price of a townhome, but Thrive's reputation and the energy-efficiency of its houses.

Wilson and his wife Gale obtained a loan and entered a sale contract.

"Then the city changed the rules at the last minute and we no longer qualify," Wilson said.

"As I understand it the city's concerned about people not being able to make their mortgage payments," Wilson said. He said the lender that approved his loan for an Elements townhome calculated that his family's housing costs would be 37.5 percent of income.

"I'm two and a half percent under-qualified," Wilson said. "I'm just speechless.

"It seems ridiculous that somebody is willing to lend me money and take the risk but the city says, 'No.'

"Our rent is $200 more than what our (mortgage and fees) payment was expected to be," Wilson said.

Wilson said he would have saved money on commuting and expected his energy costs to be low. Some experts have said such transportation and utility costs also should be considered when determining whether a family's housing costs are too burdensome.

OED's Fisher said she could understand the frustration of people like Wilson.

"A home is an important thing. It's a dream for some," she said.

Her department was working on ways to improve communications to ensure home buyers, developers, realtors and lenders understood the rules and were aware of them early in the process, Fisher said. Counseling agencies had also been contacted as OED considers adopting a policy of referring potential buyers who would be cost-burdened for follow-up review. Housing counselors could determine if an exemption could be made. Home buyer counselers might also direct people to downpayment assistance programs.

Myers said Thrive was trying to find buyers who could meet the 35-percent standard, which often means providing a hefty downpayment. In the meantime, Thrive had stopped seeking lots and pulled back on requesting construction permits for more affordable housing. Myers said Thrive could cut prices, but feared that would affect the value of the Elements homes already sold, leaving earlier buyers owing more than their places were worth.

Myers said he hoped the mayor and City Council members would intervene.

Robin Kniech, an at-large member of the council, said she was reserving judgment while awaiting results of research into how other cities with affordable housing programs vet potential buyers. But she said she was inclined to defer to OED.

"They're trying to find a rule that will stand the test of time," the councilwoman said.

Now, Kniech said, OED was being criticized for being too strict. If the economy slows and buyers run into trouble, "people will be quick to blame the department for letting people get into houses that they can't afford."