If Denver was on a dating app, its profile would probably focus on its view of the Rockies and its bountiful sunshine -- its best self. The frequent smells of pet food and faraway farms seem like more of a fifth date sort of thing.

Denver's full of stench. Weed, a pungent and unmistakable odor, is pretty easy to identify. But tar and dead animals and creosote and various chemicals, from an industrial corner just north of Denver in Adams County, mesh to form a stinky cocktail that's more ambiguous. The various stinks spread to Globeville and Elyria-Swansea south into other parts of the city.

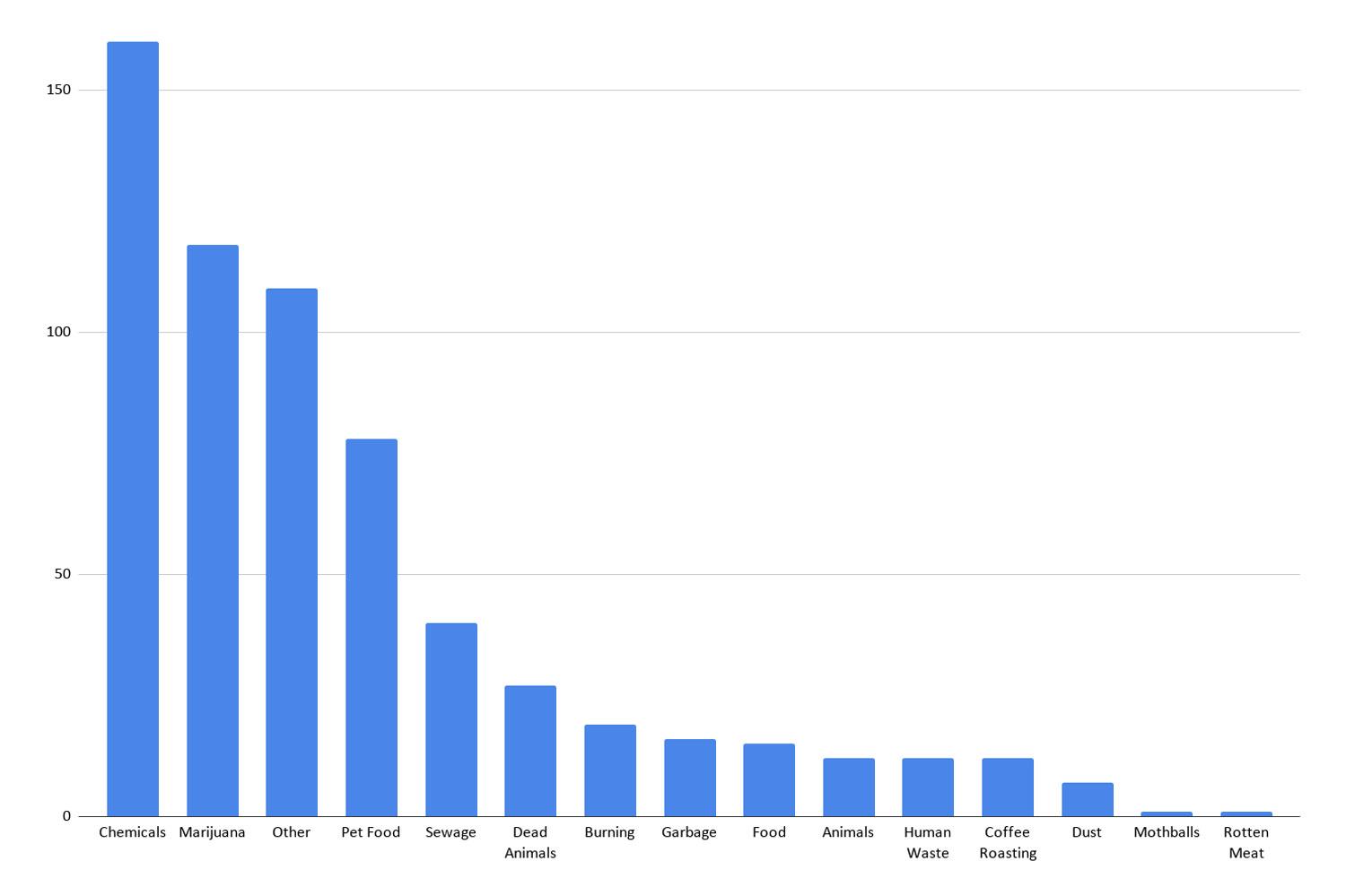

In an attempt to make sense of our noses, we mapped smells by analyzing nearly four years worth of complaints, from 2016 to September 2019, sent to Denver's public health department.

We also mapped the good stuff. This job was less scientific because no one complains to the city about aromas of ice cream and grilled grub.

So: Who's stinking up the place?

Industry. Also, your neighbors.

Light green = Chemicals, Yellow = Sewage, Green = Marijuana, Blue = Other (unidentifiable), Purple = Pet food, Brown = Human waste, Black = Garbage, Orange = Food, Pink = Burning, Teal = Dead animals

There are two basic types of smells: the ones that a lot of people whiff collectively (the Purina plant) and the ones only noticed by people nearby, like the "rancid, death poop odor" one person found in her basement, according to the city's database.

Let's start with the smells everyone smells: pet food, marijuana and obscure-smelling things that most people can't really pin down (represented by "Other" in the map). For instance, complainants used phrases like "rotten eggs" and "burning rubber" and "burning plastic" to describe what could have been any number of smells.

"As redevelopment continues moving north along Brighton Boulevard, the odor issue isn't going away," said Gregg Thomas, who directs the city's Environmental Quality Division, part of the Denver Department of Public Health and Environment. "There's probably about a half a dozen different industries that are the primary odor generators and they are all distinct in their own ways."

While the precise smells may be a mystery at times, the sources are not. According to a University of Colorado study published in April of 2019 in the International Journal of Environmental and Public Health, the following plants and factories are responsible for the Big Smells whiffed throughout the city and especially in north Denver.

- Suncor Energy, an oil refinery that can have a number of chemical smells

- Nestle Purina Pet Care Co., which makes pet food and smells like pet food

- Koppers Inc., a creosote wood treatment facility that makes things like telephone poles and can smell like tar and asphalt.

- DARPRO Solutions, also known as Darling International, an animal rendering plant that can emit the smell of dead animals

- Owens Corning Denver Roofing Plant, which can smell like tar or burning things

- Trumbull Asphalt Plant, which can smell like tar or burning things

- MetroWastewater Reclamation District, which can smell like sewage

- Cobitco Inc., an asphalt company that can smell like tar and other chemicals

- National Western Stock Show Association, which can smell like farm animals

- Altogether Recycling, which can smell like various chemicals

- METech Recycling, which can smell like various chemicals

Exhaust fumes from cars and trucks on I-70 and that farm animal smell, which comes to us from dozens of miles away, were also major offenders.

What we smell and when we smell it depends on which way the wind blows, literally and politically.

Many terrible smells don't originate in Denver proper. They come from plants in Adams County or further away. That stinky farm animal smell comes from hog and cattle feedlots an hour or more northwest of Denver in Greeley, La Salle and other parts of Weld County, according to Thomas from the environmental health department.

A lot of animals share a small space, they feed a lot, they excrete a lot. Some waste particles get whipped up into the air and sent Denver-bound by cold fronts and other weather systems. Other particles end up in nearby ponds. They go airborne through condensation and brought to Denver before it rains.

That's why you always smell the stench before it rains or snows.

"It just tells you how strong the smell will be at the source if you're smelling it two hours later after it mixed with fresh air," Thomas said.

Unpleasant smells also, of course, come from what's allowed to be released into the air. During a campaign event last year, Mayor Michael Hancock claimed that the Purina plant doesn't smell anymore. Most people laughed. It does still smell.

The mayor was referencing stricter odor rules that require companies to have a plan for masking smells. Purina, for example, added new filtration tech. Same with some marijuana grows. But the smells persist.

Shelly Miller, who co-authored the CU study with Mohamed Eltarkawe, sat on a board that helped shape the legislation. She applauds the ordinance but thinks industrial polluters can do better.

"That has been a really huge step in the right direction because I think if we want Koppers, for example, to reduce their emissions of creosote -- which they should because its a carcinogen and very toxic. We have to see if they can be good neighbors and work with the neighborhood and meet with them to do their processing at a different part of the day, for example."

The Suncor oil refinery, situated a stone's throw from homes and businesses, is one of the worst polluters in all of Colorado. It also smells bad (though DDPHE says many smells blamed on Suncor probably come from other industries). Violations, which are relatively common, result in fines but the Canadian company is within its legal right to do business as usual.

Bad odors are bad for well-being. At the very least.

Miller and Eltarkawe's study initially set out to link stinky smells to physical health problems. More than 300 people in her study reported headaches, difficulty breathing and asthma attacks.

And North Denverites reported breathing problems, dizziness and even "acrid" and "bitter" tastes in their mouths that accompanied overpowering odors. But it's all anecdotal.

"The odor research right now is very old and limited," Miller said. "We wanted to prove health effects but we didn't have the resources to do that, first of all. And it's difficult to prove the connection between specific health effects and odors."

So they set out to link bad smells to mental health and quality of life. She says they did.

Voluntary corporate governance and better filtration tech is in the best interest of the plants and factories, says Thomas from the public health department. They will only see more pushback as development concentrates people closer and closer to the source of the stink. Regardless of what the science says so far, "people aren't going to be OK with not being able to have their kids playing in their backyard," he said.

Now, clean your nostrils imagining these good Denver smells.

This map is not so scientific. It comes from polling Twitter users and our newsroom. Wheat Ridge used to have a Jolly Rancher factory. Who knew? (A lot of people knew.)

This article was updated to add cattle feedlots as an odor source.