City workers loaded tents into bins Thursday morning at the start of a cleanup of encampments scattered throughout Five Points.

Nancy Kuhn, a spokeswoman for the city, said the cleanup was prompted by concern that the public right of way was being blocked and that health and safety was being undermined as the area became "increasingly hazardous."

Advocates for people experiencing homelessness said the cleanup endangered health, citing guidance from the Centers for Disease Control that clearing encampments during the COVID-19 outbreak can scatter people and cause them to lose touch with service providers, which could make it harder to stop the spread of the disease. Because they often have other health concerns and their immune systems can be weakened by the stress of living on the streets, people experiencing homelessness are considered at greater risk of suffering the worst effects of COVID-19.

David Scott, standing next to his tent as a parked garbage truck nearby rumbled, said he would move for the cleanup and hoped to return to the site later. But he said when he had moved a few months before from a nearby site, he had returned to find the spot covered with large, jagged rocks that made camping impossible.

Scott said he had been a concession and maintenance worker at Denver sports stadiums but did not earn enough to afford housing even before those jobs disappeared because of COVID-19. Large gatherings such as for sports events have been banned to try to slow the spread of disease.

Kathleen Van Voorhis of the Interfaith Alliance of Colorado had called for the cleanup to be cancelled as a matter of public health and "human dignity."

"These sweeps are about turning a blind eye to the humanity and basic needs of individuals experiencing homelessness," Van Voorhuis said in a statement. "By telling individuals to move along without a plan for where, the city of Denver is causing more harm than good."

Tamara Boynton, a pastor and director of strategic engagement for the Interfaith Alliance, was among a group of clergy handing out breakfast burritos and observing the cleanup Thursday morning. She gave her card to Anthony Ayres after hearing him describe having returned to living on the streets Tuesday after completing a nine-month prison term for criminal trespassing.

"I don't know where to go," he said, describing shelters as places "where I feel incarcerated."

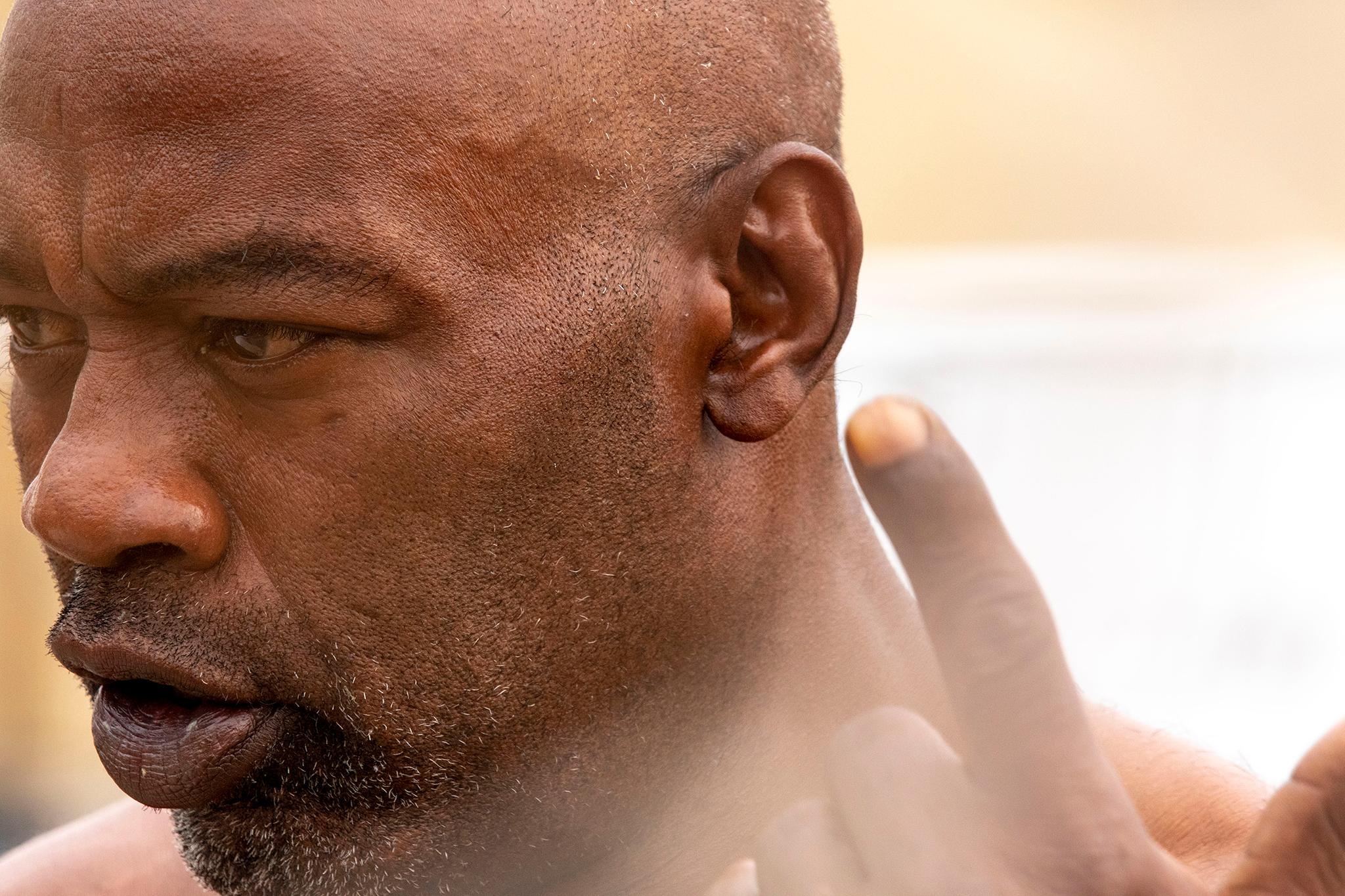

Ayres said he was 34 and has lived on the streets on and off since he was 16. He said friends who were experiencing homelessness had welcomed him to their encampment when he left prison and that he would rely on them as he tried to decide what to do next.

"I don't want to be out here," he said. "There's COVID. Sometimes it rains. Sometimes it's cold. Sometimes it's too hot."

In addition to housing, Ayres said he wanted work, but knew the disease outbreak had hurt his prospects.

"Where do I go to sign up for a job?" he said. "Everything is closed. People are losing their businesses."

Boyton, the pastor, said she would try to connect Ayres to support.

In an email last month, Alton Dillard, another city spokesman, said that since the new coronavirus outbreak began in mid-March, the city's practice has been to clean encampments but not clear people from them.

Terese Howard, an activist with the advocacy group Denver Homeless Out Loud, said the city was not clearly telling people experiencing homelessness that they did not have to move for cleanups.

"They just leave people in chaos and confusion," Howard said Thursday. "They refuse to admit that they're allowing people to survive in public space."

City spokeswoman Kuhn said in an email that the city was asking people to move Thursday "so that we can thoroughly clean. What we have seen, historically, is that people will move to the next block during our cleanings and come back when the work is complete."

Marty Lavine, who lives in an apartment building just outside the area targeted for cleanup, would like a longer-term solution.

Lavine, a physical therapist, had to close his gym business because of public health rules imposed to try to reduce the spread of COVID-19. He faces the possible loss of a business he has owned for 16 years.

"We're all trying so hard, and then I walk out there and it's like everything I'm doing is for naught," Lavine said, adding that he has seen people experiencing homelessness who camp in the neighborhood failing to practice the social distancing that experts say is needed to control COVID-19.

The CDC says people living in camps should provide at least 12 feet by 12 feet of space per person and should be provided 24-hour access to toilets and hand washing facilities. The city has provided some toilets and hand-washing stations, including a portable toilet that was parked along 21st Street between California and Stout streets Thursday morning. Denver Homeless Out Loud is paying for four on 2nd Street at Curtis, Champa and Stout streets and at the corner of 21st and Welton streets.

Homelessness is "really complicated, I get that," Lavine said. "But something's got to give. It's beyond not OK."

Lavine dodges needles and broken glass at the camp sites when he bikes or walks in his neighborhood. He was concerned that litter and human waste around the camp sites poses other health risks.

Since the first coronavirus cases were confirmed in Denver, the city and partners such as the Denver Rescue Mission and Catholic Charities of Denver have opened 24-hour shelters equipped with cots and portable showers at the National Western Complex and the nearby Coliseum. The National Western shelter was designed to accommodate 600 people and has held more most nights since it was opened, an indication that people want shelter. The Coliseum has room for 300 women, and both new shelters have enough space for guests to practice social distancing.

Other shelters had to close so that staff could be consolidated at the new shelters, so the move did not add substantially to the city's shelter capacity. The city and its partners also have secured more than 500 hotel rooms and are seeking more for people experiencing homelessness who are affected by the coronavirus outbreak.

According to the latest point in time survey, which gives a snapshot that is likely an under-count, about 4,000 people are experiencing homelessness in Denver on any given night.

Faith-based groups and organizations that provide housing, health, employment and other services for people experiencing homelessness have been pressing the city for a sanctioned camping area with hygiene, sanitation and health services to provide another alternative for people experiencing homelessness during the coronavirus outbreak. Mayor Michael Hancock has long opposed sanctioned camping, saying the city must offer more dignified shelter. The coronavirus outbreak has not changed the mayor's mind.

Elsewhere in Colorado, officials in Longmont are cautiously studying the possibility of "safe lots" outside churches or community centers for people living in their vehicles.

In Denver on Wednesday, Rayshawn Bradford moved east from the area targeted for Thursday's cleanup. He and seven other people set up a camp on a vacant lot at 33rd and Curtis streets with tents at least six feet apart. Bradford said he lost a job as a waiter because of the coronavirus outbreak, which has led to restaurants closing their dining rooms. Even when he was working, Bradford said, he'd only been able to afford to live in a hostel.

He said Denver Homeless Out Loud helped outfit the camp with garbage bags and bins and he hoped the organization would be able to set up a portable toilet nearby. He had ridden his bike to Five Points earlier Thursday to shower at St. Francis Center's day shelter and planned to spend the rest of the day looking for work and trying to determine why he had not yet received unemployment benefits.

Bradford said he believed shelters were crowded and unhealthy. He said he would live on the streets until he could save the security deposit and first and last month's rent it would take to get into an apartment, but worried that even then, with employment prospects uncertain, he might one day end up evicted for failure to pay the rent.

As Bradford spoke, fellow campers picked up trash. He said he hoped that if they kept their camp clean and neat, police would not ask them to move along.

"That's all we're asking for, until this (the COVID-19 outbreak) blows over," he said.

"All we want is to survive," he said. "We deserve to survive."

Kuhn, the Denver spokeswoman, said Thursday's cleanup fell under the rules established last year when the city settled a class action lawsuit filed by people experiencing homelessness.

The plaintiffs in the federal suit had challenged the way city employees handled their belongings during a series of street cleanups in 2016. The settlement's provisions included requiring the city to give written notice seven days before embarking on a "large-scale" clearance of belongings and enact policies to ensure the return of property confiscated during clearances. The city offers up to 60 days' free storage of belongings that do not pose a public health or safety risk. The tents city workers were packing up on Thursday appeared headed to storage.

Kuhn said outreach workers would be trying to connect people to resources and services during Thursday's cleanup.

She said notices of Thursday's cleanup were posted a week ago by Denver's Department of Transportation and Infrastructure, once known as Public Works, throughout a three-by-five-block area in five Points from 20th to 23rd streets (which is Park Avenue West) and from Welton to Curtis streets.