While it's been two years in the making, a placard unveiled downtown Friday seems well timed in a year of racial justice protests inching closer to an election.

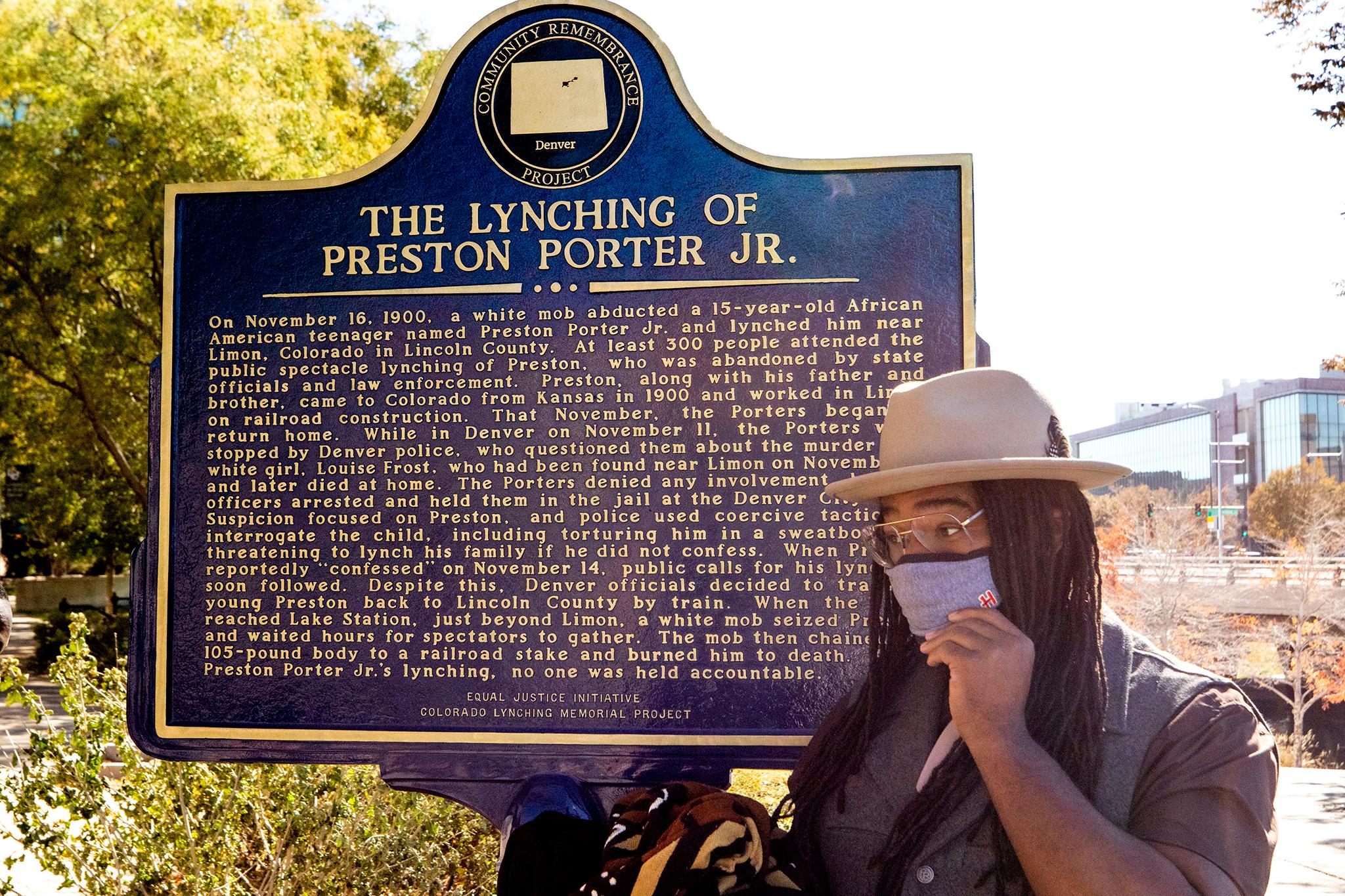

"On November 16, 1900, a white mob abducted a 15-year-old African American teenager named Preston Porter Jr. and lynched him near Limon, Colorado," the embossed text reads. "At least 300 people attended the public spectacle lynching."

Porter was working on the eastern plains with his father when he was accused of the rape and murder of a white rancher's teenage daughter. He and his father fled to Denver, where he was soon arrested and jailed inside the old city hall at 14th and Larimer streets.

The sign memorializing him sits nearby, beneath the University of Colorado Denver's building downtown and across the street from Larimer Square. It was created by the Equal Justice Initiative, which keeps records on nationwide racial terror, and Colorado Lynching Memorial Project (CLMP), which documents cases in the state.

According to their research, Porter was "tortured" in a "sweatbox" while he was held in Denver. He reportedly confessed to the crime after four days in custody.

"The Denver authorities, knowing he was going to be lynched, handed him over to the sheriff of Lincoln County," CLMP's Judy Ollman said. "He never made it that far."

Instead, a white mob pulled Porter off the train when it reached Limon. They chained him to railroad ties and burned him alive in front of a crowd.

"The sinister, grim nature to plan and carry out something like that was so unique," Jovan Mays, a CLMP member, said. "That spectacle gained the attention of Mark Twain, and others, to write about how we thought westward expansion would kind of dilute the terror."

It did not.

For Ollman, Mays and their colleagues, the new sign is a way to remind Denver residents that racial terror occurred here, the same way it did in other parts of the nation. Ollman said Porter's death has never received the broad awareness it deserves.

"It never fully surfaced to where everybody can feel that they know this is part of Denver and Colorado's history, that we do have this history of racial terror violence," she said. "We're hoping that this marker might do that, might be the way that we finally recognize the history and accept it."

CLMP's website lists the lynchings of seven African Americans between 1881 and 1902. It also recognizes 19 "people of Hispanic ancestry, at least four of Italian ancestry and at least two of Chinese ancestry who suffered death at the hands of lynchers."

Even though they have been working toward this memorial for several years, Ollman said its message is crucial right now.

"Until we really acknowledge our history, we can't even understand what's happening today. We can't fully understand why the death of George Floyd is described as a present day lynching. It's only when you go back and you see the thread that goes all the way from back in the 1860s, all the way to the present day, that you can really see that," she said. "All of these lynchings need to be known and recognized in order for us to heal."

This new placard comes as Denver wrestles with other iconography in town. During the summer of protests, the Union soldier statue on the Capitol's west steps was toppled, as was a statue of Christopher Columbus in Civic Center Park. Another visage, of Kit Carson, at Colfax Avenue and Broadway, was taken down by the city to avoid potential damage. The Union soldier statue is now on display at the History Colorado Center, where it will remain for a year.

Mays said the sign dedicated to Preston Porter is a step in a different direction.

"This conversation about monuments [is about] whether they're honest and whether they're showing a true depiction of an environment. And yeah, we're doing it," he said. "It feels really good to be a part of a team that's doing it, too."

While its unveiling was a fairly low-key affair, it will pave the way for a larger recognition on Nov. 16, the 120th anniversary of Porter's death. Ollman said CLMP is lining up elected officials to speak during a virtual dedication ceremony.

Meanwhile, Denver Public Schools students are invited to participate in an essay contest, which Mays said poses a "gargantuan" question: "How does our history with racial injustice impact what we're experiencing today, and how do we overcome it?"

Students who wish to tackle this query can sign up on CLMP's website beginning on Sept. 17.

Correction: A typo in the original version of this story made it sound like Porter died in the 1990s. It was corrected.