Few can raise money like Mike Johnston. The former state senator broke donation records in his unsuccessful runs for Colorado governor and U.S. Senate.

His run for mayor has been no different -- he's been described as a "fundraising machine" this election cycle.

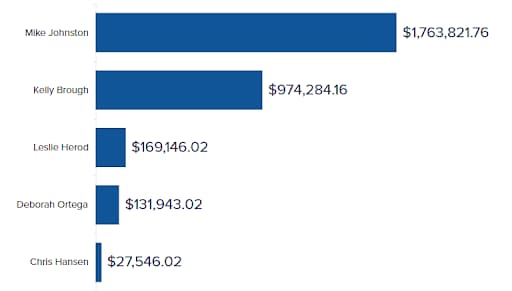

Johnston has the most total money supporting him: $2.9 million. That's $555,782 more than Kelly Brough, the next closest candidate in fundraising.

More than half of the money supporting him, though, is outside his direct control, in a super PAC called Advancing Denver, which has collected about $1.8 million in contributions.

Super PACs, long a part of state and federal elections, have come to Denver in a big way. That's thanks in large part to Johnston being in the race. He has a history of billionaire donors backing him through independent groups. Donors he likely met through his work on education reform issues, giving him a national profile.

U.S. Supreme Court decisions solidified a place for super PACs in American politics, and this outside money was probably always going to find a way to Denver; this is a competitive election for a coveted political seat, at a time when TV and social media channels have made campaigns vastly more expensive.

"Would I like a world to exist in which super PACs didn't exist? Of course," political analyst Eric Sondermann said. "It's Denver politics becoming part of the oligarchy -- which is the ultimate, ultimate wealthy, whose only interest in Denver is maybe as a stopover on the way to Aspen, are increasingly controlling this race."

Sondermann also said that reforms passed by city voters in 2018, designed by activists to get big corporate money out of elections, banning LLCs and lowering limits in exchange for taxpayer contributions, have helped to push major donors into these super PACs, also known as independent expenditure committees, or IEs.

The donors contributing to super PACs are free of the city's strict money limits but are forbidden from coordinating with candidates.

Johnston considered bolstering the super PAC himself, asking the Denver Clerk and Recorder last month if he could transfer money from his aborted 2020 U.S. Senate run, an account with more than $1 million still in it, to Advancing Denver.

The Clerk said there wasn't enough information to rule, and Johnston eventually decided against the transfer.

Johnston's campaign would not elaborate on the relationship he has to the various donors of Advancing Denver, saying it respects the independence of the committee.

"It operates totally separately from Mike and the campaign," said Jordan Fuja, communication director for Johnston's mayoral campaign. Fuja said many know Johnston from work on education, housing affordability, or budget reform issues. "I think these people are excited about the possibility of Denver becoming a proof point for the nation in tackling tough challenges like addressing homelessness and housing affordability."

Fuja noted that Johnston has received more than $600,000 in Fair Elections Fund money, a taxpayer-funded match on small individual contributions to his campaign from Denver residents -- the second largest match, behind only Kelly Brough, which shows Johnston isn't just boosted by billionaires.

Half a dozen other mayoral candidates have an independent expenditure committee supporting them. The committees backing Johnston and Brough are the largest, but Johnston's super PAC is in a class all its own, with more reported contributions than all the rest combined.

The lion's share of the reported contributions into Advancing Denver, the IE supporting Johnston, came from a group of out-of-state donors (between his campaign and his super PAC, 67% of his non-Fair Elections Fund contributions come from out of state) : $779,804 from Reid Hoffman, co-founder of LinkedIn, who lives in California; $250,450 from Steve Mandel, a hedge fund billionaire who lives in Connecticut.

Another $100,000 came from John Arnold, a former Enron trader from Texas known as the "King of Natural Gas," who along with his wife gave to Advancing Denver. (Arnold was cleared of wrongdoing in the collapse of Enron.)

None of these donors returned calls for comment. It's unknown how they crossed paths, what issues exactly they worked on together in the past, and why they care specifically about Denver. The closest to an explanation came from a post on Linkedin by Hoffman recently.

"Cities are the places where creative entrepreneurs with political courage can develop and deploy big ideas that become proof points for the country," Hoffman wrote. "My friend Mike Johnston, who is running for Mayor of Denver, is one of the most creative and courageous political entrepreneurs I've worked with."

Having money, experts generally agree, is better than not having money, even if some donations raise awkward questions.

Still, big outside contributors have not been decisive for Johnston in previous campaigns. His Frontier Fairness PAC, when he ran for governor in 2018, raised $5.8 million from some of the same donors now funding his mayoral race. Yet he finished third behind Cary Kennedy and Gov. Jared Polis, who self-funded, spending more than $24 million.

This election is different. Johnston has the clear edge in money this time. And with so many people in the race, 17 mayoral candidates are listed on the ballot, name ID from a barrage of ads could help more than raise concerns about who's paying for it.

"I question whether the average voter who has that ballot sitting on their countertop, and is looking at those 17 names, knows this information the same way those of us watching every step in this race," said Councilwoman Robin Kniech, who is term-limited, having won three citywide elections. She hasn't endorsed any mayoral candidate.

Kniech said it could become an issue if Johnston makes the runoff, it's down to just two candidates, and attack ads possibly start. "If he makes the runoff, it's the number one attack ad," she said.

Red-boxing

The outside money can be spent in support of a candidate, but the campaign doesn't have control over how the PAC spends the money, or how it designs ads. A close observer of the TV ads run by Advancing Denver, or any other PAC, will notice the ads are filled with archival photos and video, and will often show images of websites and newspaper articles to help get the message across.

An ad directly from a campaign, meanwhile, is different, often including the candidate themselves, addressing the viewer directly with a carefully crafted message about their vision for the city.

Campaign websites try to signal to outside groups the messages and voters that they want to target, but the websites are dense, filled with policy proposals and bios and calendars. So some campaigns have recently found a way to push specific messages to the super PAC without directly coordinating, through something called "red boxing."

Red boxing was noticed on Democratic campaign websites last year, as a way to subtly coordinate messaging.

"Red boxing," said Saurav Ghosh, Director of Federal Campaign Finance Reform Program at Campaign Legal Center. "Is named after the traditional red outline around material that's supposed to be for the select audience of Super PACS, that are trying to figure out what to run in their ads."

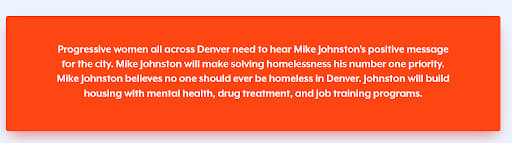

At the bottom of the "Meet Mike" section of Johnston's campaign website was a not-quite-red (more orange-red) box with a peculiar message.

Advancing Denver seems to have got the message, and built an ad for these voters with many of the keywords. The ad, called "Search," aired frequently on local TV.

The message in the red box starts: "Progressive women all across Denver need to hear Mike Johnston's positive message for the city. Mike Johnston will make solving homelessness his number one priority."

In a woman's voiceover, Advancing Denver's ad starts: "What would Mike Johnson's top priority be as mayor? Addressing homelessness."

Johnston's red box continues: "Mike Johnston believes no one should ever be homeless in Denver. Johnston will build housing with mental health, drug treatment, and job training programs.

Advancing Denver's ad: "Johnston has a detailed plan to fight homelessness, building additional housing units along with necessary drug treatment, mental health, and job training services."

The box was removed from Johnston's campaign webpage late last week.

That's "kind of another telltale sign," said Ghosh. "Red boxes tend to disappear once they've served their purpose."

Fuja, the Johnston campaign spokesperson, didn't directly answer if it was a red box message or not. She said the box was removed because the website is undergoing changes.

"We're in the middle of updating our website," Fuja said. "Adding some pages and doing that stuff. Everything on our website is public information. We regularly highlight Mike's positions and his priorities across the website."

Red boxing is allowed by federal election regulators, said Ghosh, with the reasoning that what's on a campaign's website is "a message broadly available to the public."

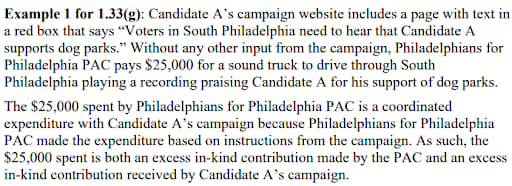

But Ghosh and others in the democracy advocacy community believe it is coordination, and at least one city agrees. Philadelphia has taken aim at the practice. In the code, the board of ethics provided an example of prohibited coordination, with the same "voters need to hear" formulation that Johnston used.

Never too much money

Sitting in a U.S. Senate campaign account controlled by Johnston is $1.1 million with nowhere to go. It is left over from his record-breaking fundraising in 2020. Johnston dropped out of the race when John Hickenlooper got in.

That much money could make a big difference in a city election.

So on Feb. 17, Johnston asked the Denver Clerk and Recorder if he could transfer that money into the IE that supports him, Advancing Denver.

"We are pursuing such a transfer in the near future," wrote Sarah Mercer, a volunteer attorney for Johnston's senate committee, to the Clerk. "And, in order to promote transparency and compliance with Denver's campaign finance rules, are seeking an advisory opinion to confirm that an entity's use of such funds to pay for an independent expenditure in support of the candidate is not controlled by or coordinated with that candidate."

Mercer argued that the transfer would not violate rules against coordinating, because Johnston doesn't control how the IE would spend the money: "the entity will be entirely in control of the transferred funds and no expenditures, if the entity makes any, will be 'pursuant to any non-public communication' with Mike or his federal candidate committee."

Mercer said Johnston would give the donors to his U.S. Senate race a chance to get their contribution back, if they didn't want to support his run for mayor of Denver.

The city's clerk, however, said there wasn't enough information to make a specific ruling on the transfer.

Mercer told Denverite, in a statement, that ultimately Johnston decided not to go ahead with the transfer. "In order to avoid distracting from the most important issues facing the city, the Senate campaign has decided not to transfer any unspent funds to the mayoral race in this election, and has not spent any money in any way connected to the mayoral race," wrote Mercer.

Despite that, Johnston appears to have a commanding lead in the money race, and his deep-pocket donors are among the richest people in America. Should he make the runoff, he will likely maintain his preternatural ability to raise money, both directly and indirectly.

And for now, more money is better than not enough, in this very low information election, said Curtis Hubbard, a political consultant and former politics editor of The Denver Post.

"Most voters could name more Denver Nuggets than Denver mayoral candidates," Hubbard said. "I won't say independent-expenditure committee contributions are a non-issue, but in an election with so many unknowns, and given the serious issues facing Denver, any spending to bolster name ID and message will do more good than harm."