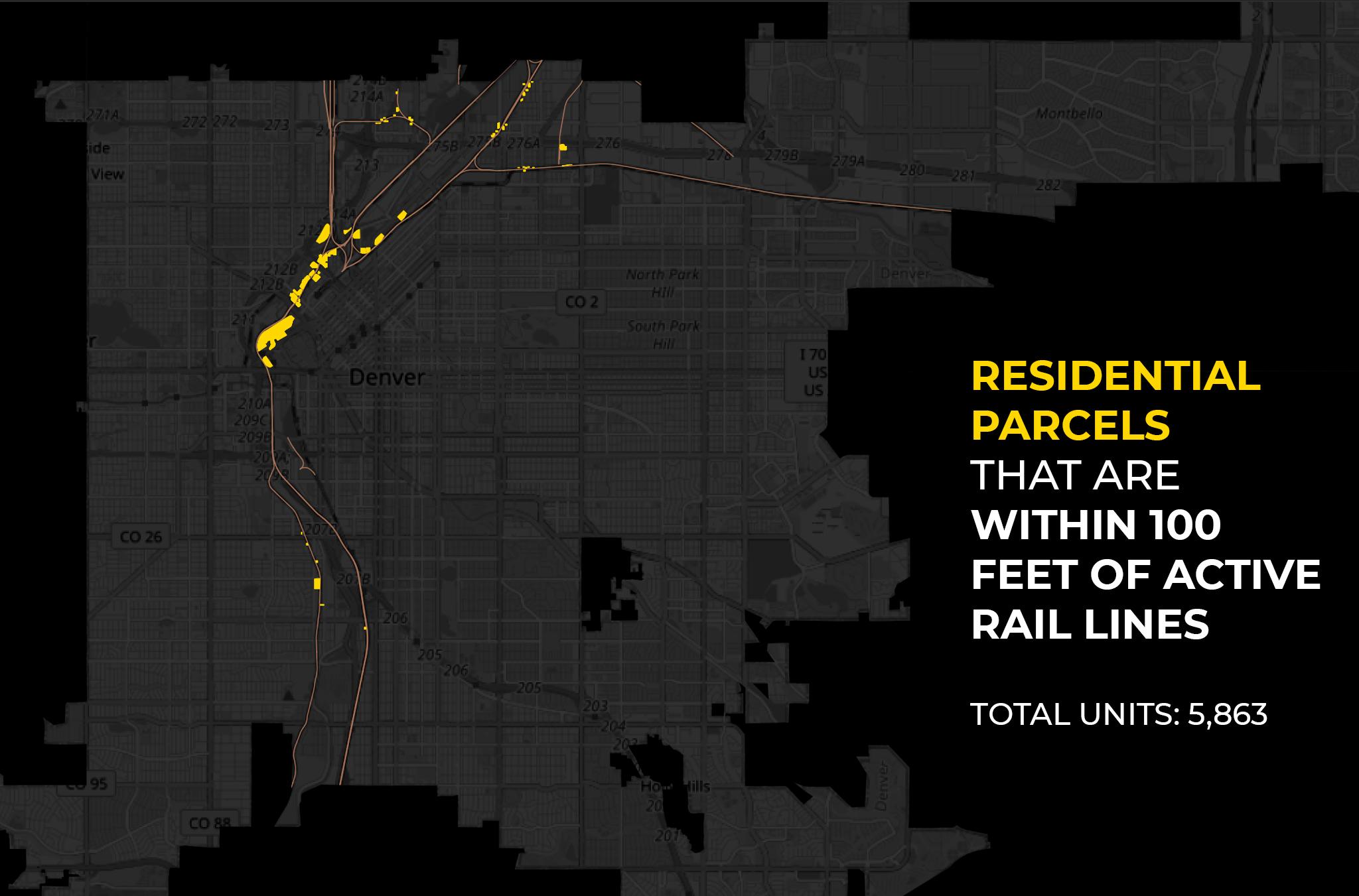

Editor's note: This story has been updated with the results of the Council vote. We've also corrected a map in this story that originally used incorrect source data and contained an analysis error. The original map from a Colorado Department of Transportation database was outdated and contained inactive rail lines. The original analysis also counted buildings multiple times, substantially inflating the total unit figure we cited. Denverite deeply regrets the error.

Updated at 5:33 p.m. on June 26:

A bill to regulate development within 100 feet of railroads in Denver failed Monday night.

Councilmembers Stacie Gilmore, Kendra Black, Jolon Clark, Chris Herndon, Chris Hinds, Amanda Sandoval and Jamie Torres voted against the proposal, while Councilmembers Candi CdeBaca, Kevin Flynn, Paul Kashmann, Robin Kniech and Debbie Ortega voted in favor.

The bill would have required developers to build 100 feet away from freight rail tracks, or choose from a range of safety precautions aimed at mitigating the harms of a potential derailment.

Ortega, who spent years raising alarms about the potential harm of rail accidents, studying the issue and working on the legislation, expressed frustration with the outcome.

"It just befuddles me that there is this strategic effort to completely undermine the work that's been done with all of our agencies at the table, working with an engineering firm, we paid $180,000 to do this work," Ortega said. "To say, 'We think that work doesn't mean a damn thing,' it's very disturbing. I've never seen a process like this that's been so undermined by agencies."

The Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen, a union representing rail workers, sent a last minute letter in favor of the bill.

"We thank Councilwoman Ortega for her continued and tireless efforts on this issue and applaud the fact her Railroad Safety Ordinance 22-1102 works to ensure the safety of Denver's citizens and visitors as well as ensure the safety of our members who work the rails here in the Mile High City," wrote Paul Pearson, Chairman of the Colorado State Legislative Board and member of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen.

But Councilmembers who voted against the bill spoke about their concerns that the city agencies tasked with implementing the changes have advocated against the ordinance, including Community Planning and Development, the Office of Emergency Management, the Department of Transportation and Infrastructure and the Fire Department. Mayor Michael Hancock also voiced opposition to the bill.

Department leaders and Councilmembers expressed concerns that the cost of implementing the bill might not be worth the safety benefits and that the city's focus might be better spent on evacuation planning. Others thought rail safety is an important issue but that the exact bill under consideration missed the mark.

"I wish that we were supporting Councilwoman Ortega and passing an ordinance that she had been working on since 2014," said Councilmember Amanda Sandoval before the vote. "But it is not good policy and I cannot be in favor of something where four major departments come out on it."

Our original story follows below.

On June 16, a BNSF train carrying oil tankers derailed in Commerce City outside the Suncor Refinery. Luckily, the tanks were empty, avoiding potential environmental contamination and safety hazards.

But freight rail lines run through the heart of Denver, and harmful derailments have happened before. In 1983, the city evacuated more than 2,000 people after a railroad car spill created a plume of nitric acid gas, injuring 11 people. In 1995, a railcar leaked 3,300 gallons of muriatic and hydrochloric acids near a community center in Swansea. And in 2022, a BNSF train derailed into the South Platte River, closing the trail. No injuries were reported.

Councilmember at-large Debbie Ortega has spent years requesting money for studies, working on legislation and trying to raise alarms about railroad risks in Denver. Her work will culminate Monday, when Council will take an initial vote on legislation that would require developers to take extra safety precautions when developing within 100 feet of railroad tracks in the city.

The bill is up for a first read on Monday. If it passes, there would be a second and final vote a week later, and then the bill would head to Hancock's desk for a signature or veto. Or it could get voted down in Council, as it faces opposition from the mayor's office, a string of city agencies and fellow Councilmembers.

But why is there so much resistance?

The proposed bill targets development near railways because track safety is regulated and deregulated at the federal level.

While City Council cannot control what happens on the freight tracks that run through Denver, it does have control over land use next door. Ortega's ordinance would require developers to build 100 feet away from railroad tracks, about the average length of a freight car, or go through extra safety requirements in permitting. Currently, Denver does not have any extra permitting or safety requirements for developers building near railroad tracks.

There are currently almost 6,000 units of housing in the city on parcels that are within 100 feet of active rail lines, according to an analysis conducted by Denverite. They are largely concentrated in RiNo and around Union Station, but there are also clusters in University Park and Central Park.

Under the proposed bill, if developers choose to build within that 100 feet, they would have to get special approval from city agencies, include an analysis of emergency vehicle access, create an evacuation plan and choose between what Ortega calls a "menu" of options to shore up safety. This might look like extra structural reinforcements, raised land or walls between the building and the railroad or elevating the structure above the railroad. The ordinance would only apply to new buildings or existing buildings undergoing major renovations.

"I want to be really clear that some people think this is a property rights taking. Land use is the responsibility of local government," Ortega said when presenting the legislation to the Land Use, Transportation and Infrastructure Committee in June. "We tried the voluntary approach. It didn't work, nobody's doing anything to address this issue."

Ortega says a bill like this is necessary because Denver is vulnerable to railroad accidents, and that the risk will likely go up in coming years.

Recent national derailments have drawn attention to the potential risks of freight rail. In February, hazardous cars derailed near East Palestine, Ohio, causing mass evacuations, environmental contamination and health hazards. And a highway collapse in Philadelphia in June showed the risks of just one oil tanker, after a truck carrying a tank caught on fire and destroyed part of the highway.

Then there are safety concerns about railway operations. In recent years, rail companies fought to kill updated brake requirements for hazardous cars, while rail workers have complained about long hours and unsafe working conditions. A ProPublica investigation showed how freight trains are getting longer, growing profits for companies but increasing the chance of derailments.

According safety studies Ortega pushed for and that was led by the Department of Transportation and Infrastructure, around 102,000 cars carrying hazardous materials passed through Denver in 2021. But the U.S. government is on the cusp of approving a controversial rail line out of an oil basin in Utah that could bring an estimated 383,000 hazardous cars through Denver by 2025.

According to data from the Federal Railroad Administration, the City and County of Denver had 215 railroad incidents, 11 fatalities and 142 injuries between 2017 and 2021.

Development around rail is also on the rise. There are big projects like Ball Arena, along with calls to build more transit-oriented development, with residential and commercial projects built close to passenger rail stations to reduce car dependency. Many Regional Transportation District (RTD) lines share infrastructure with freight rail, which means building housing near transit requires building near freight railways as well.

Ortega said she does not just worry about freight risks - in March, an RTD train derailed in Golden, injuring two people. While RTD does not carry hazardous materials, Ortega said derailment hazards go up when the trains run close to residential buildings.

But city officials in opposition to the bill are skeptical about whether potential added safety benefits are worth the cost of implementation.

Community Planning and Development Executive Director Laura Aldrete, Department of Transportation and Infrastructure Executive Director Adam Phipps, Office of Emergency Management Director Matt Mueller and Fire Chief Desmond Fulton sent a joint letter to City Councilmembers in May voicing their opposition to the ordinance.

In the letter, the department leaders wrote that a cost benefit analysis is needed given how rare major rail catastrophes are. Officials were skeptical that the proposed bill focuses on the right issues or if it would have mitigated damage in a situation like in East Palestine, given the massive scope of environmental contamination. They also think that Denver does face safety risks, but that the most pressing investments need to come in the form of neighborhood evacuation planning for potential hazards like wildfires or hazmat evacuations like in East Palestine, rather than focusing on derailment risks.

"Numerous hazardous materials related rail incidents across the country have demonstrated that a threat to life and property exists near heavy rail," wrote Mueller in the letter. "However, this risk should also be put into context given the scope and frequency of impacts in relation to other hazards threatening Denver."

Grady Cothen, a former Federal Railroad Association safety official who has written white papers on rail safety, said that railroads are safer than they were decades ago, and that the risk of derailments decreases in major cities because trains have to slow down when moving through major metropolitan areas. Still, he said there are other risks like noise. There is also the rare potential for incidents with sitting cars in rail yards. Cothen said his main safety concern with railroads in cities is pedestrian and vehicle collisions at crossings.

"I think most urban planners who have looked at this issue closely would agree that putting high density residences right up against a freight rail right-of-way is to be avoided, if possible," he said. "All over the United States this is an issue, and if there are options for building at some reasonable distance from an active rail line, then I think you would seek out those opportunities, but it would have to be balanced with the desire for transit-oriented development."

Some Councilmembers have already expressed opposition to the bill.

Councilmember Amanda Sandoval, who chairs the Land Use, Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, recommended the full Council vote down the bill. She called the letter from the four city agencies a "huge red flag."

"In the 11 years I've worked, I've never seen a memo come out from four agencies that explicitly outlines why they aren't supportive of something, and it's the four agencies that have been part of the stakeholder committee," she said. "Getting this memo, it's huge. I've never seen it before."

Council President Jamie Torres said in a committee hearing she planned to vote no. Other Councilmembers feel mixed-that the issue is important, but that the exact bill might miss the mark or not be worth the costs. Councilmember Stacie Gilmore represents District 11, parts of which almost needed to evacuate during the Marshall Fire and which faces a lack of public transportation. She said her priorities are evacuation planning.

"Weighing those different, very important priorities with limited resources, is something that I'm really struggling with," she said in a committee meeting considering the bill.

In addition to questions about costs versus benefits, opponents have a long list of other concerns ranging from permitting times to graffiti.

The letter from department leaders says the bill lacks detail and would be difficult to actually implement, expressing concerns about a lack of staff to implement changes and worries that the ordinance would extend already lengthy permitting times for new development. City officials also took issue with the fact that the ordinance only works at decreasing the risk of derailments, without addressing risks of incidents on the tracks and hazardous material releases.

The department leaders also wrote that they want to see more testing and evidence that the mitigation measures would actually make properties safer. They worry that protective walls along tracks could attract graffiti, and that elevating properties above track-level would "lead to a deterioration in street level activation" in pedestrian areas. The letter also says the bill could "deteriorate our public realm and a sense of safety on our streets."

The Fire Department said that building 100 feet away from the tracks could create a "false sense of security for the public." Fulton wrote that the city is "best served by reactive measures" by focusing on hazmat tools to reduce active hazmat releases.

In committee hearings considering the bill and through emails to councilmembers, representatives for private developers have also pushed back against the proposed ordinance.

Rhys Duggan, one of the developers behind the massive railroad-adjacent River Mile Project, said that throughout the process it was not clear whether his current plans would qualify under the ordinance, and that the bill would add to existing permitting delays.

"This Council Bill attempts to address a safety issue that seems to rank well behind other more pressing public safety concerns in the city, such as homelessness, addiction, violent crime, and vehicular/pedestrian accidents," Duggan wrote in a letter to City Council. "Surely our time and limited city resources can be put to better use."

Mayor Michael Hancock, who would either sign or veto the bill if it were to pass Council, said he is opposed to the legislation. In a statement, he said it would be "virtually impossible to implement" and further delay permitting.

"While the goal is laudable, the proposed solution would not solve for catastrophic events and was developed without the public input process the city would typically undertake before proposing new codes or regulations on this scale," he said in a statement to Denverite. "Any local regulations should also be crafted in partnership with the railroads and Federal Railroad Administration, whose responsibility it is to regulate rail safety, to ensure they are meaningful and effective."

There's a reason officials are unsure of the efficacy of preventative safety measures: very few cities in the U.S. have tried approaching rail safety from the local level.

Ortega said that when she first began working on railroad safety, she reached out to the National League of Cities, which works with city leaders across the country on a range of issues. She could not find peer cities taking similar approaches.

Brittney Kohler, Legislative Director of Transportation and Infrastructure for the National League of Cities, said that since the East Palestine derailment, she has seen an increased interest from cities in looking at railroad risks. But Kohler said she has not heard of cities working on proposals like the one in Denver; officials are focusing instead on supporting federal legislation around safety.

"We have seen tremendous Canadian work on overpasses and underpasses for railroads so that you are doing a better job of keeping both trains and people moving and safe," Kohler said. "Most U.S. communities are thinking along the lines of 'How can rail service, particularly passenger and commuter rail service, be a part of our larger economic developments?'"

Without peer U.S. examples, Canada is exactly where Ortega said she drew inspiration and credibility from in developing the local bill. In 2013, a derailment in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec killed 47 people and destroyed part of downtown. Earlier that year, the Railway Association of Canada and the Federation of Canadian Municipalities passed national guidelines for development along railways, which include things like building setbacks, noise mitigation efforts, safety barriers and fencing. Some cities like Calgary have taken the requirements a step further with their own regulations, but other rail safety efforts focused on trains and tracks themselves have stalled.

But Aldrete, who runs Community Planning and Development, told Council during a committee meeting that the focus on Canada's plan is one of her problems with the bill.

"I don't believe zoning is the appropriate tool to increase safety, and I think we would have seen that in national best cases across the United States should that be the right answer," she said. "However, we do not. We have one city in Canada that has a different governmental structure that has recommendations for how you build that that discussed land use. Outside of that, nobody else in this country is doing it."

With Ortega term-limited in July, work on regulating development near railroads could end when she leaves office.

In response to city officials' concerns, Ortega said she held a number of engagement meetings with city agencies and developers, and that the request for additional studies would require more funding. Ortega asked for funding for her initial 2016 safety study cited in the bill, but only received about half of what she asked for from the mayor's office. She said the biggest ask from developers was for flexibility, which led to the model allowing developers to choose from a range of safety precautions.

"We've been raising this red flag issue since 2014, and any of the agencies could have had the opportunity to say, 'You know what, we're going to come to the table with a way of how to solve that.' None of them have attempted to do that," she said.

And while incidents like pedestrian deaths or other traffic accidents are much more common than freight rail incidents, Ortega said it is not a fair comparison, given how catastrophic a single derailment could be.

"They're comparing the risks from these kinds of situations that are really important for the city to be working on and addressing," she said. "We don't minimize the importance of that, but we think this is equally as important because [of] the kind of impact that can happen to lives lost, property lost, to commerce being shut down."

Ortega said it feels like groups opposed to the bill are just waiting for her to run out of time, and she is not sure if anyone will continue work on the issue after her.

"I may go away, but this problem is not going to go away," she said.

Denverite visual journalist Kevin Beaty contributed data analysis reporting to this article.

Editor's note: This article has been updated to correct the number of hazardous cars and to clarify that the Department of Transportation and Infrastructure led the rail safety study.