Urban preservation nonprofit Historic Denver installed two new plaques Thursday, highlighting a pair of sites that community members deemed historically significant.

For its 50th anniversary, Historic Denver whittled a pool of public submissions down to 50 locations. The group then began working with property owners to figure out an appropriate way to highlight their buildings’ stories. Strategies include helping the owner preserve the building, advocating for a landmark designation or documenting its history.

Historic Denver ultimately determined that installing plaques would be the best way to designate the histories of the two buildings it commemorated Thursday.

One plaque was installed at the site of a supermarket-turned-taproom.

Residents of Denver’s Skyland neighborhood, north of City Park, nominated Ben’s Supermarket, a corner store that used to sit at the intersection of East 28th Avenue and York Street.

The market was first opened by Toshimune “Ben” Okubo, a Japanese-American who moved to Denver after being released in 1945 from Camp Amache, a World War II-era internment camp in southeast Colorado officially known as the Granada Relocation Center.

“Going from Granada to Denver is a really common migration story,” Historic Denver Director of Community Programs Alison Salutz said. “And the story of this particular family here, they came to Denver, they lived nearby, and they started operating what was called Ben’s Supermarket right after the war and continued to operate it into 1961. It was a store, but it was also a community fixture.”

The Okubo family sold the store at 2301 E 28th Ave. in 1961, but it continued to operate under the Ben’s Supermarket name until 2020.

Salutz said Historic Denver heard from several residents who frequented the store with their families. The store was conveniently located along two streetcar lines, and it spent years as the only source of fresh food in a neighborhood without walkable grocery stores.

After the market closed in 2020, the current property owners leased the building to Ephemeral Rotating Taproom. Visitors to the taproom can still see echoes of the past. On one wall, the original sign from Ben’s Supermarket hangs above shelves of common pantry items.

Ephemeral co-owner Shannon Lavelle said she and her business partners wanted to keep the spirit of the supermarket alive after hearing about the building’s history from longtime residents and their landlord.

“We have market staples like flour, sugar, baking soda, because that's a lot of what people would come here for,” Lavelle said. “Just local snacks, penny candy. Whole dill pickles were a big thing that people in the neighborhood growing up said they would come in after school to grab, so we made sure to keep a lot of that kind of fun fare in it.”

Salutz said preserving the stories of the Okubo’s and other interned Japanese-Americans is important, as it forces Americans to reflect on a dark part of the nation’s shared history.

“This was a particular moment in the war where people were incredibly afraid, but a similar sentiment may happen again,” she said.

A second plaque was installed in RiNo.

Before Denver’s River North Arts District was a smorgasbord of expensive outdoor clothing retailers, brewpubs and food halls, it was the city’s industrial center. It was also home to Julia Greeley, an emancipated slave who became known as Denver’s “Angel of Charity” once lived.

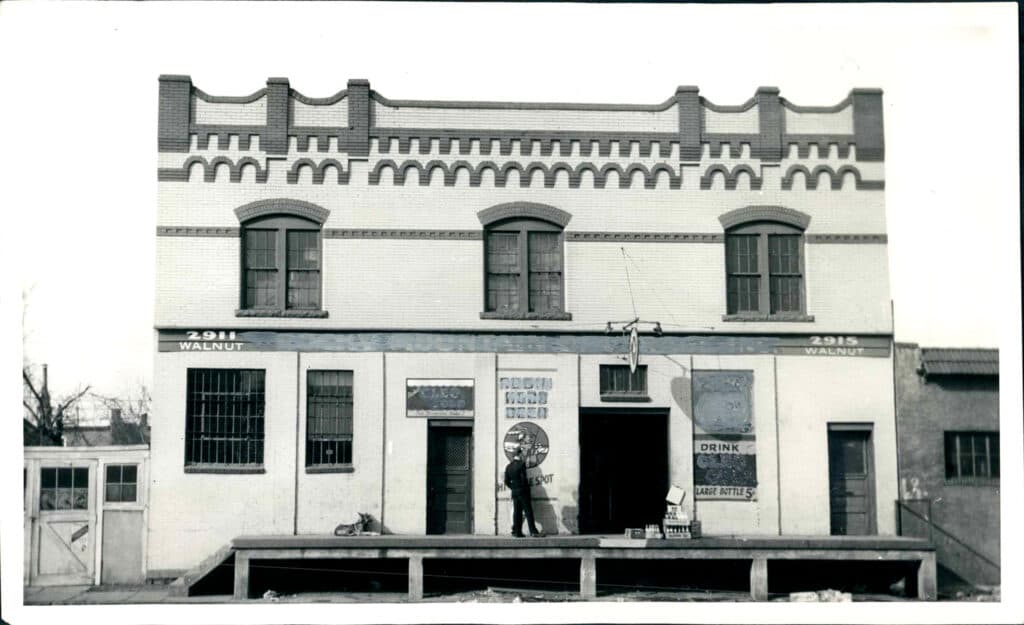

Historic Denver has now installed a plaque at 2911 Walnut St., the site of a former boarding house where Greeley used to live.

After being freed from slavery in Missouri around the time of the Civil War, she moved to Denver to work for the family of William Gilpin, Colorado’s first territorial governor. There, Greeley converted to Catholicism and spent most of her time helping impoverished families with the wages she earned.

“She would've come out here in the 1860s,” Salutz said. “So this is really early in Denver's past, and she had such an impact on so many individuals' lives. And when she died, her funeral was attended by hundreds of people who lined the block to pay their respects.”

In 2016, the Archdiocese of Denver petitioned the Vatican to consider canonizing Greeley as a saint. The Vatican is currently reviewing the case, but the canonization process can take decades. Greeley is one of a handful of African American Catholics recommended for sainthood, a status the church has never granted any African American person.