Denver’s savings are low, the national economy is uncertain and the city’s budget is on shaky ground.

In response, Mayor Mike Johnston plans to reduce general fund spending by about 6 percent from 2025, merging departments, slashing offices and cutting homeless shelter sites, marketing campaigns, contracts and more.

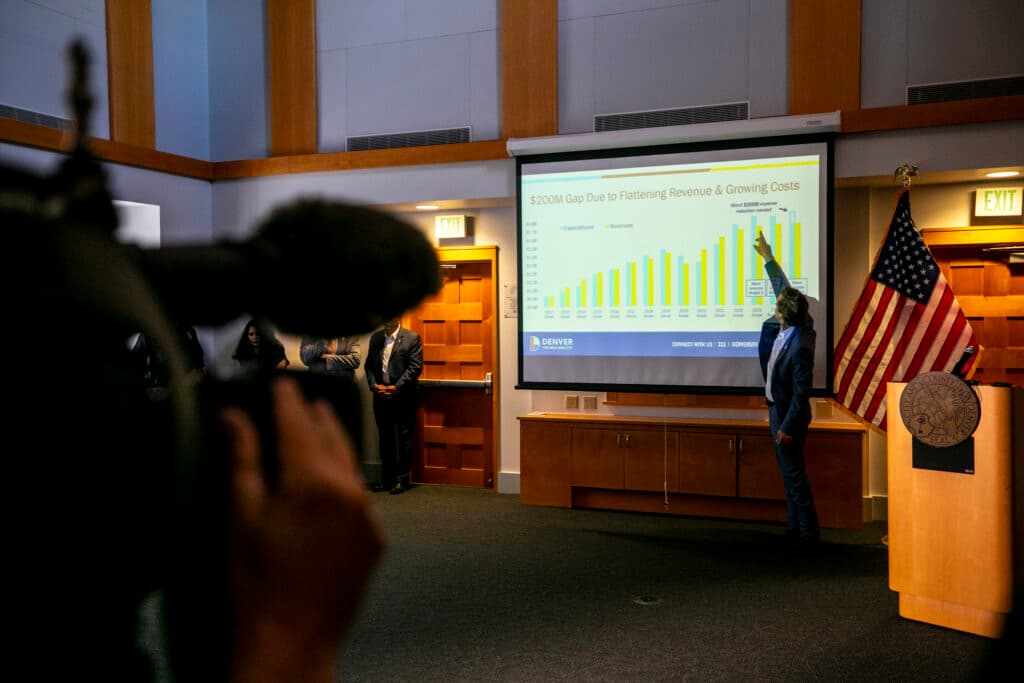

The mayor says he’s fixing over a decade of bad city spending habits, and it could just be the beginning. The proposed 2026 budget would cut spending by more than $100 million from this year and $200 million compared to earlier projections.

“You really do have to reduce the size of city government,” Johnston told Denverite. “You have to deliver a government that works better and costs less.” He points out that other cities are facing similar struggles.

But the mayor’s critics tell a different story. Some blame his spending on homelessness and immigration, while others say he ignored warning signals.

“He bankrupted the city,” said third-term Councilmember Stacie Gilmore, whose husband lost his job in a recent round of layoffs.

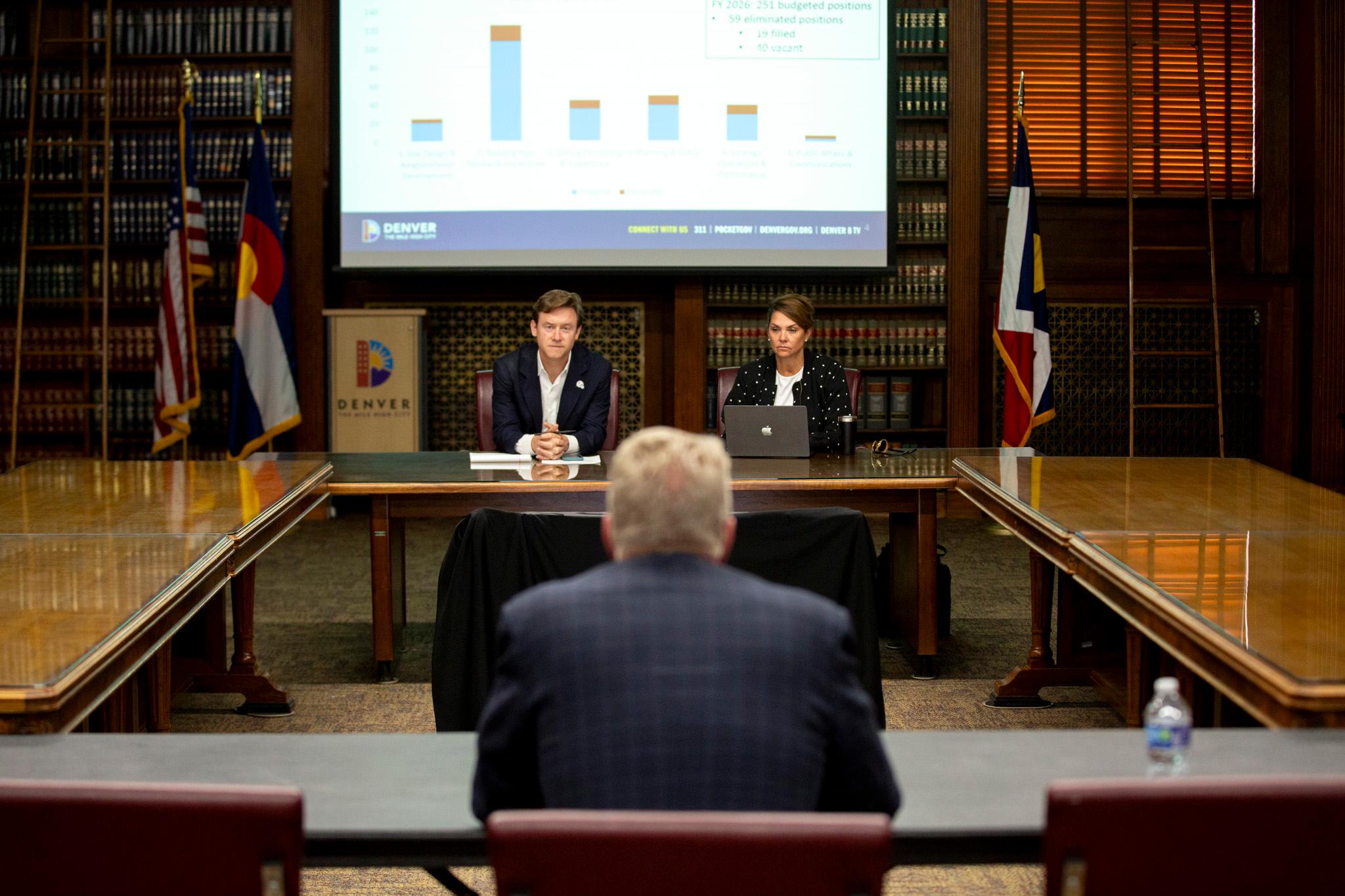

The stakes are significant. Johnston laid off about 170 city employees and closed hundreds more open positions, some of the city’s biggest cuts in decades. Independent agencies like the courts also saw cuts.

The proposed budget would mark one of the few times this century that a Denver mayor has intentionally planned a budget reduction. And even with Johnston’s proposal, the city could still be vulnerable to an economic downturn.

So, how did this happen?

Johnston says years of spending have put the city in a bad situation.

The number of Denver employees has grown faster than the population — adding about 40 percent to its employee count and 70 percent to its general fund spending since 2012. Meanwhile, the city’s population has grown by only about 15 percent. That’s been a central talking point for Johnston.

“We have to live within our means. It's what every family in the city does. And so we think that we, you know, we don't think that we need to grow at 40 percent to 70 percent over time to be able to provide core services," he said.

Johnston has implicitly put some of the blame on his predecessor, former mayor Michael Hancock, who ran the city from 2011 to 2023.

When Hancock took office, the city was still recovering from the Great Recession, and its budget was reeling. But by 2014, Denver was booming. Its general fund spending grew by an average of 7 percent between 2014 and 2019.

Hancock defended his administration’s spending in an interview with Denverite. He noted that he oversaw the city through a period of intense growth, as well as the pandemic and the subsequent recovery.

“We had extraordinary boom times, which required us to ramp up to meet the services of this new population and demands of development that were occurring in the city,” Hancock said.

Meanwhile, voters passed multiple new taxes to pay for everything from affordable college tuition to climate and homelessness response, increasing the tax load and the size of government.

Denver recovered faster and better from the Great Recession than most cities, said former Councilmember Robin Kniech. As it did, the government grew to meet increasing demands.

Individual departments like Parks and Recreation, Tech Services and the Office of Economic Development saw their budgets grow significantly, and the city launched new programs focused on housing stability and mental health.

Despite all the growth, Hancock said he managed the budget responsibly.

Denver’s savings grew — then shrank.

Like most cities, Denver keeps reserves to spend in case of an emergency. The city tries to keep savings equal to at least 15 percent of general fund expenditures.

Under Hancock, the city almost always hit its savings goal, though it still ran a deficit in some years.

“Whether we were in boom or bust, we wanted to make sure we had 15 percent,” Hancock said.

Hancock did dip below that target when the pandemic hit. In response, he froze hiring, furloughed workers and paused pay raises for police, sheriff’s deputies and firefighters. Through it all, he avoided mass layoffs.

Then, Hancock enjoyed some macroeconomic luck: Federal emergency support flooded in, and local tax revenue rebounded quickly.

By 2022, the city had healthy reserves of 26 percent. But the city’s spending was growing, too, and trouble was ahead.

The turning point was 2023.

Johnston took office in July 2023, inheriting Hancock’s spending plan for the year.

The new mayor had made big promises to voters. On his first full day in office, Johnston swore to end street homelessness.

Then came another new challenge. Thousands of new immigrants had begun arriving in Denver in 2022 with little warning and nowhere to stay. In the fall of 2023, the influx grew faster. Johnston and City Council set up shelters, work authorization programs and legal clinics, a widely popular move at the time.

“We made an intentional decision to be compassionate when the governor of Texas started busing people up here from the border and dumping them on our doorsteps in the middle of the night, the middle of the winter, in front of the governor's mansion,” Councilmember Kevin Flynn said.

The homelessness and immigration programs came at a cost. The Johnston administration estimates it spent a total of $87 million on new immigrant services in 2023 and 2024 and around $57 million a year on homelessness, not including the purchase of long-term shelters and hotels.

Meanwhile, revenue growth began to soften due to an uncertain economy. With slowing income and higher costs, Johnston temporarily reduced spending at parks and motor vehicle offices in 2024. Even still, the city spent $108 million from its reserves that year — dropping below its savings target.

Today, former City Councilmember Debbie Ortega wonders if the city could have done more to collaborate with other governments and charities to defray the costs of its biggest challenges.

“It takes a village,” she said.

The immigration crisis eventually subsided, with new arrivals dropping dramatically. But at the same time, the city continued spending heavily on housing, shelter and health care, even as federal assistance dried up.

Johnston argues that he responded early and aggressively to signs of budget trouble.

While some expenses have kept growing, Johnston has slowed the overall expansion of the general fund.

In 2024, his first full year in office, general fund spending increased by about 5 percent, with the mayor cutting or slowing departments like Finance and Tech Services. That was a significant slowdown from the prior year, returning the city to a more typical growth rate.

Among other changes, Johnston strengthened a “position review committee” to oversee city hiring. (Hancock launched that effort in May 2023.)

Then, Johnston says, the city wrote a conservative budget in fall 2024, anticipating less revenue growth for 2025. The city slowed hiring and reduced positions at the beginning of this year.

“We reduced the growth of government in a city that normally sees 5 percent revenue growth every year. We projected half of that,” Johnston said. “So we did start slowing.”

But the economy slowed even more than expected, resulting in zero revenue growth in 2025. Johnston blamed the uncertainty of the presidential election and this year’s trade wars. The city reacted by freezing most hiring in May — and then laying off workers and closing open positions over the summer.

Still, the city has kept spending more than it makes. The administration expects to spend another $61 million from reserves this year, drawing them down to just 10 percent of spending.

The erosion of the reserves has deeply concerned Hancock, the former mayor said.

Meanwhile, Johnston says his proposed 2026 budget is the first step toward fiscal health. By cutting spending, he expects to replenish the city’s reserves to 11 percent, or about $183 million.

But that’s still below the target, and it could leave the city vulnerable if the economy significantly weakens.

Has Johnston cut enough?

Despite the cuts, critics say Johnston has ignored some savings strategies.

Unlike Hancock, Johnston has not offered early retirement incentives to employees. Instead, he ordered department heads to close vacant positions and carry out layoffs.

Meanwhile, Johnston has pushed for raises for police, fire and likely sheriff deputies, even as other city workers won’t likely get raises. Uniformed employees also avoided furloughs.

In contrast, both Hancock and former mayor John Hickenlooper saved millions by convincing police unions to accept delays in salary increases.

“Sometimes we had to have tougher conversations with them,” Hancock said. “But for the most part, most of them just stepped up and said, ‘We’ve got you.’”

Johnston also will not ask voters to raise sales taxes to support the general fund. He fears higher taxes would discourage people from shopping and exacerbate the city’s affordability crisis. That’s conventional wisdom shared among many city leaders.

“You can't nickel and dime businesses and households to a point where, you know, they're choosing to go elsewhere,” Ortega said.

Overall, Johnston said the city can't cut much deeper without impacting core services.

Denver is far from alone in facing a tough budget season.

Twenty of the nation’s 25 largest cities are facing budget gaps, according to data from the Pew Research Center.

But why?

“Many cities are facing budget deficits and fiscal stress, driven by weak revenue growth, lingering office vacancies due to remote work, transit ridership that hasn’t fully recovered, higher labor/pension costs, among other city-specific fiscal pressures,” wrote Lucy Dadayan, a researcher with the Urban Institute, a city-focused think tank, in an email to Denverite. “Several cities had to close budget gaps and enact cuts.”

Some larger cities like Chicago and Los Angeles are facing budget gaps of $1 billion or more next year.

In this state, Colorado Springs has an $11 million budget shortfall and plans to lay off almost 40 employees. Aurora has a $20 million deficit, and it is making cuts but plans no layoffs.

“There's a lot to be nervous about with the state of the economy,” said Denver city economist Lisa Martinez-Templeton. “We're right on the precipice of an economic downturn.

Even as Johnston makes cuts, he’s planning to spend big.

While he’s reducing short-term spending, the mayor has proposed major infrastructure projects around the city.

This November, he’s asking voters to approve the Vibrant Denver bonds package, which would include about $950 million for projects and potentially $900 million in interest over several decades. The proposal wouldn’t require a tax increase, but it would prolong the payback of the city’s existing debt.

In the next year, Johnston hopes to continue to build affordable housing with public dollars, solidify the purchase of land for a new women’s soccer stadium and finish a deal to keep the Broncos in town. Meanwhile, the Downtown Denver Authority is set to invest hundreds of millions more in the city center.

Johnston argues that even as the city tries to save money and replenish its savings, it needs to make long-term investments to keep its economy growing.

In the coming months, the city’s voters and its elected leaders will weigh in on that vision — and their decisions will shape the second half of Johnston's first term in office.