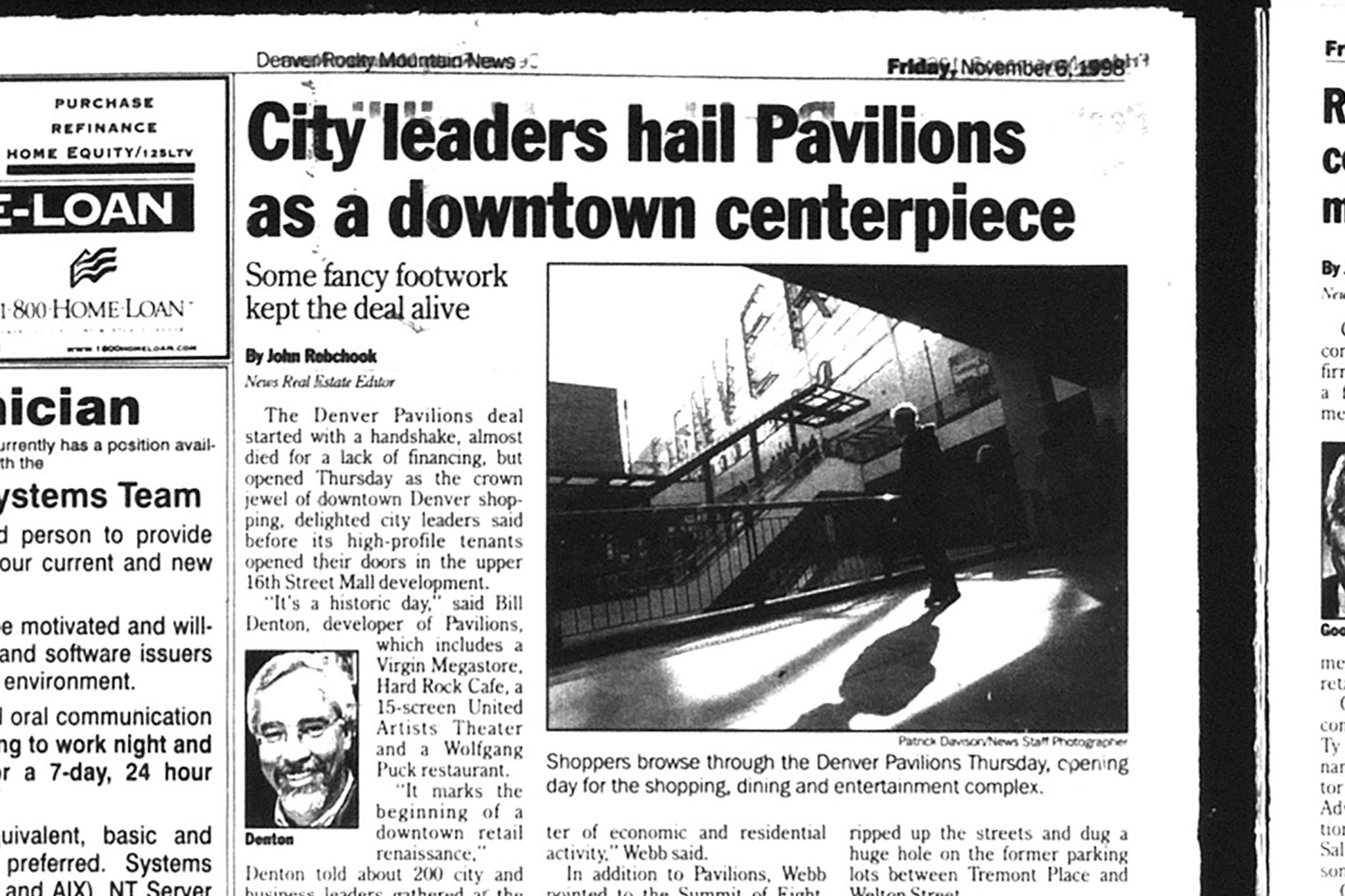

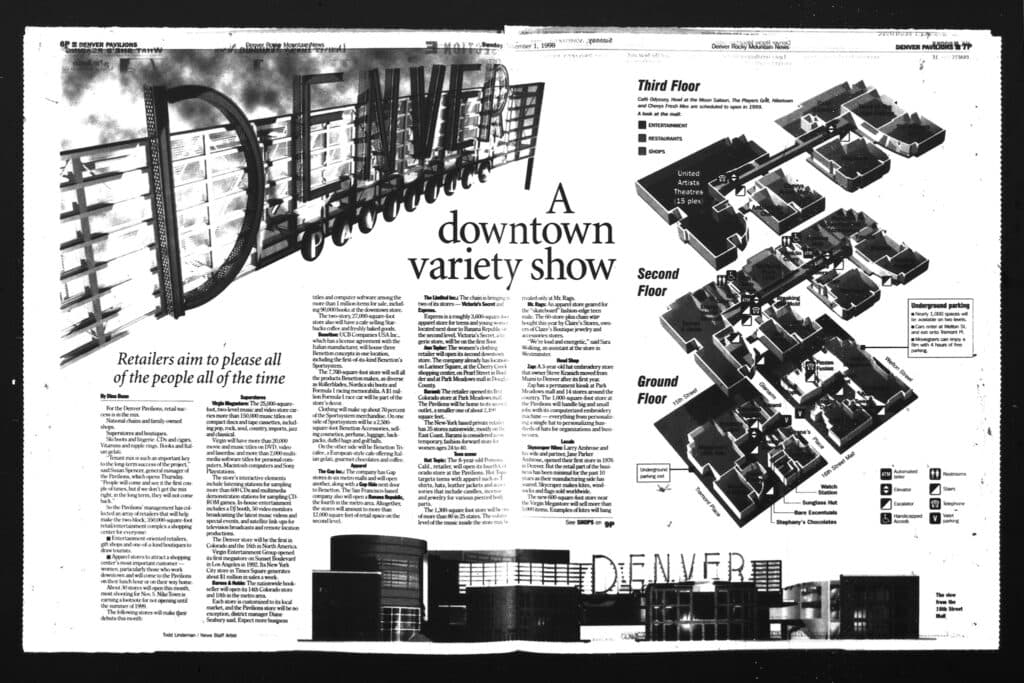

In November 1998, Denver’s leaders celebrated a moment they had planned for years: the opening of a three-story shopping mall — emblazoned with the city’s name in gigantic neon lettering.

“The Denver Entertainment & Fashion Pavilions,” sitting along 16th Street, was the finishing touch on a decades-long effort to reinvent Denver’s urban core, powering it out of the malaise of the ‘80s.

The local government and the property’s developers had pumped tens of millions of dollars into the project. In return, it was expected to draw hordes of locals and visitors alike — and their tax dollars.

“It was successful, until COVID,” recalled developer Susan Powers.

Now, that crown jewel is looking pretty tarnished. Pandemic-era closures, a surge in work-from-home culture and years of construction on 16th Street have left many of its storefronts vacant. The crowds that once gathered here have become harder to spot.

In March, the owner of the property — which is now known as Denver Pavilions — said it faced tough finances and a possible foreclosure. Then, a few weeks ago, a city authority announced it would buy Pavilions for $37 million, a fraction of its former value.

The purchase, which is still pending, is an attempt to rescue the flailing property from closure. Mayor Mike Johnston is relying on a reinvigorated downtown to rebound from a $200 million budget crisis, and a dead mall would be a threat to that recovery.

Officials say it would be a risk to sit on the sidelines and let Pavilions’ future play out on its own. But if Denver does succeed in buying the property, the city could be carrying a new liability into a fraught economic future. And there’s also a chance it all falls apart: City officials told Denverite that it hasn’t inked a deal with a financial lender involved with the mall.

Here’s how Denver’s prize mall fell into disarray — and what comes next.

Pavilions originally promised to fix the neighborhood.

City planners had been dreaming about a mall on 16th Street for decades, with the concept turning up as early as the 1980s. By the 1990s, the dream was becoming reality.

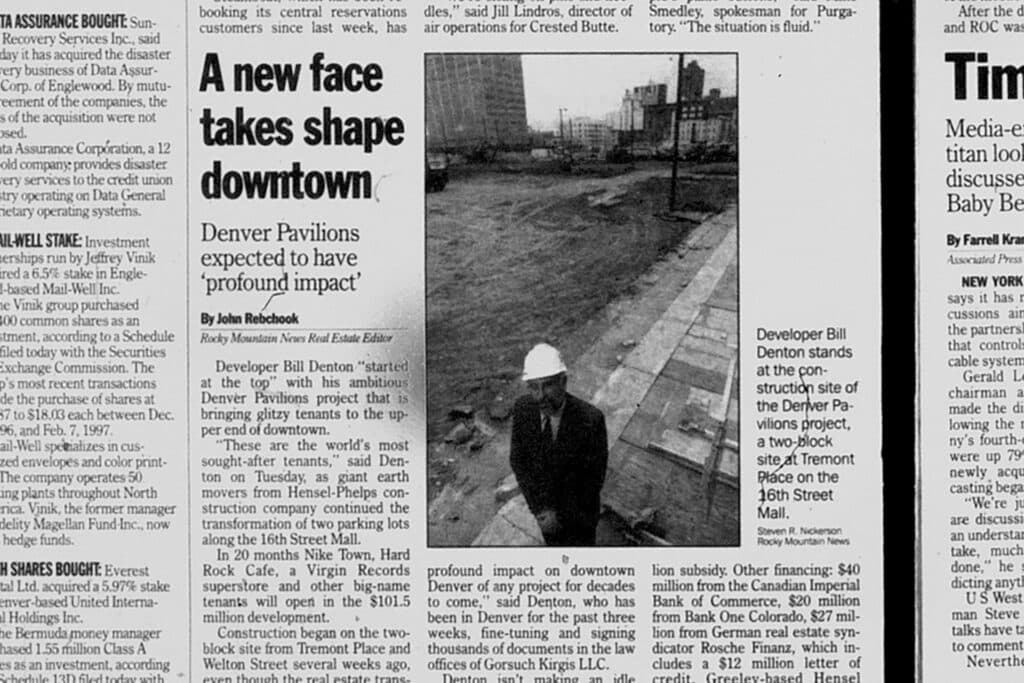

“A California developer plans a $90 million entertainment and retail project that promises to revitalize the long-suffering upper end of the 16th Street Mall,” the Rocky Mountain News read on Oct. 13, 1994.

Downtown’s image had suffered in the decade prior, thanks to an economy tied to the volatile oil business and growing investment in the suburbs. Large, longtime department stores had moved out. The closure of the Denver Dry Goods Building in 1987, a cavernous building filled with high-end shops and an elegant tea room, marked the end of an era.

“We wouldn’t be the department-store-focused downtown anymore,” said Powers, who ran the Denver Urban Renewal Authority (DURA) in the late ‘80s and ‘90s. “It took a long time for downtown, for everyone, for the administration and for us, to accept that.”

Bill Mosher, who headed the Downtown Denver Partnership at the time, said there was growing pressure to reimagine the corridor.

“We had lost all that retail, and there was the advent of the Cherry Creek Mall. There was talk of a new shopping mall at the corner of I-225 and I-25 that ended up being Park Meadows, further away,” he remembered. “Downtown felt really threatened. And so there was a real push to try and establish more and better retail on 16th Street.”

In 1994, Mosher told the Rocky Mountain News the Pavilions project would be a “shot in the arm” for downtown. Early announcements teased a “flagship” movie theater and “one-of-a-kind retailers and five-star restaurants.”

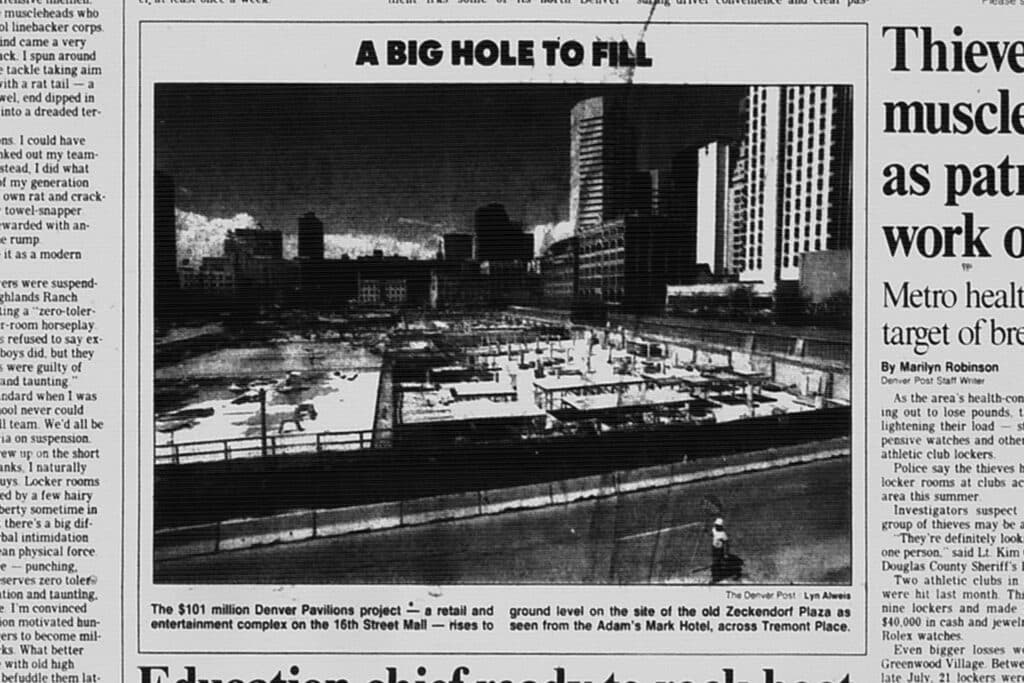

Still, Powers said it turned out to be harder to finance than expected. Though DURA promised millions to subsidize the project, developers had secured less than 20 percent of the money they needed by October 1995.

“It was lenders that didn't believe in it,” she said.

Securing the money took so long that Hensel Phelps, the construction company leading the project, eventually said “screw it” (in so many words) and started building before the financing was finalized, Powers said.

Though bankers wrung their hands about the project, Powers said city leaders were sure it would deliver for downtown.

"I think this is going to be a home run," William Denton, a developer behind Pavilions, told the Rocky in 1994. "Denver has been locked in a Catch-22. You need good retail to attract good retail. We will take on that responsibility."

Pavilions lived up to its promise, for a time.

It was completed two years later than expected, at a total cost of $105 million — including DURA’s $32 million public subsidy. And it had some issues at the start.

Niketown, one of its most anticipated offerings, delayed its debut until 10 months after Pavilions’ grand opening in 1998. The Colorado Cross Disability Coalition also sued United Artists over inaccessible movie theaters, which impacted the company’s flagship there. And chilly weather during the grand opening caused some to question its very configuration.

“I just wish this place had a dome,'' 17-year-old Logan McCash told the Rocky on opening day. “I can't be walking around in the cold.''

Still, throngs of people came to see it, waiting in line to sit in the Hard Rock Cafe and wandering into the Virgin Megastore.

“I'll definitely be back,'' Johnanna VanZaig, a local nurse on her day off, told Rocky reporter John Accola. “I think the scene is changing in Denver.''

Denverite reader James Kerley, who wrote to us about his memories of the place, said he was entranced to see it for the first time, as a kid on a school trip from out of town.

“It absolutely felt like a grand experience. I felt like I had finally made it to the big city, to a place where all the action was,” he said. “That experience stuck with me, and for years after I moved to the Denver area, that was the place I took every single visitor.”

“It felt like an exciting place to be,” reader Rachel Vigil remembered, “almost like a home base. I'm not sure it ever lived up to its intended vision, but I do sincerely love that odd mall.”

But it was never universally loved. Some people who wrote us called it “puzzling,” “uninviting” and an “ugly boondoggle.”

Mosher, the former Downtown Denver Partnership leader, said the mall did achieve what he and others promised. Ten years ago, he said, the property was valued at $140 million.

“I think it became part of the downtown experience and was successful,” he said. “It was essentially over 90 percent occupied and the sales numbers were upwards of $60 million, just within the last decade. You have to pay attention to that.”

But the mall’s hot streak ended in 2020, and the city’s leaders would soon face difficult decisions.

Pavilions is on the brink, and Denver is invested in its survival.

Mosher went on to work for the Trammell Crow development company in 2006 after a decade leading the partnership.

Last year, Mayor Mike Johnston tapped him as the city’s chief projects officer and head of the Downtown Development Authority (DDA), which was created by the city to oversee investment in Union Station in the 1990s. It is tasked with managing a special tax fund that can only be spent on improvements to Denver’s central business district.

Early this year, Mosher said Pavilions’ ownership group came to the authority with a grim warning about their finances.

Pavilions is owned by an LLC that’s affiliated with local developer Gart Properties, which did not return a request for comment in this story. Mosher said it’s “no secret” that the group hasn’t made a payment on an $85 million loan since July and was headed toward default.

“It was pretty clear that the lender and the ownership group were coming to the DDA and sort of saying, ‘How do you want to handle this?’” Mosher said. “What we have been dealing with from the beginning is the notion that if we didn't do something before the end of the year, it would go into some sort of a receivership, foreclosure-type position, and it would go back to the lender.”

What would happen if Pavilions became the center of a long legal fight, or if it were sold to someone who let it sit vacant?

Mosher and his colleagues came up with a plan: The DDA would pay $37 million to the ownership group to take possession of Pavilions, spend a year or two developing a master plan for the site and then resell it to a developer who would reliably take care of this important piece of 16th Street.

Part of the plan is to combine Pavilions’ parcel with two adjacent parking lots, potentially making it easier to sell to a future buyer. DDA set aside an additional $23 million to buy that land last July.

“The decision was, if we can't step in and have an impact on 16th through Pavilions, what can we do?” he said. “That uncertainty is, obviously, what had driven us, a little bit out of fear.”

If it works out, Mosher said this plan would allow Pavilions’ owners to settle up with the bank, and it would allow the bank to move on without having to take control of the property and resell it. It would also give the DDA a chance to guide what Pavilions becomes, selecting a buyer who would follow a menu of options that the city will create in the next year.

Mosher told Denverite that negotiations are ongoing and hinge on whether Pavilions’ lender will agree to cede full control to the downtown authority.

Mosher has stressed that the DDA — not the city of Denver itself — would buy the property, though the two are closely linked.

Downtown voters recently expanded the DDA’s ability to collect a portion of downtown tax revenue and invest it in more than $500 million of projects.

The authority collects an “increment” of downtown property and sales taxes — diverting some of the growth in downtown tax revenues to be spent on downtown projects, instead of going to the city’s general fund.

The Denver City Council would have to approve the Pavilions purchase.

Doing nothing would be a risk, but buying the property could present other dangers.

A worst-case scenario, Mosher said, would be that Pavilions falls into neglect.

Outdoor malls around the nation have experienced similar struggles, he said. The Charlotte Epicentre, in North Carolina, was also a game changer before it began to decline in 2016, spiraling as vacancies invited violence that led to more vacancies. Its owners defaulted on an $85 million loan in 2021, and it has yet to recover despite new ownership and a rebrand.

Mosher said the DDA’s involvement would ensure the property continues to contribute to downtown’s economy, but he stressed it should not be a long-term project: The DDA hopes to resell the property within a year or two after it’s purchased.

“Our goal is to get Pavilions back into private sector hands,” Mosher said. “The DDA and this mayor have felt some urgency to deal with downtown, now that 16th Street is open. How do we put a spark back and some confidence back into the private sector and spur redevelopment in downtown?”

But the authority would take on a different risk in purchasing Pavilions, said Glenn Mueller, a former University of Denver real estate professor who tracks commercial properties in the nation’s 54 largest cities. The question is whether the DDA can actually sell the property as it hopes.

“I understand the Denver development authority wanting to keep something from going dark, because then the city loses property taxes,” he said. “The question is, within one year, is there a retail owner and or developer who would be interested in taking this over?”

Mueller is not watching this deal closely, but he told Denverite that retail is generally a riskier gamble than other sectors. The fact that the mall is only 60 percent occupied doesn’t help, he added — nor do recent economic forecasts.

“There is still a good chance that we go into a recession,” Mueller said. “When there's a recession, people don't have money, they don't spend. They stop spending and all the retailers get hit hard.”

Mosher said the DDA is hedging against a downturn and is prepared to own the property for as long as five years, if necessary. The authority’s plans include financing to cover $11 million in ongoing maintenance costs.

Bigger changes downtown might help.

Jon Weisiger, who leads local retail and mixed-use projects for the international real estate firm CBRE, said cities like Denver are poised to bounce back from COVID-era slumps. He said the DDA was wise to consider purchasing the property.

“Investment is favoring outdoor strip retail space or even unique curbside opportunities that are well located in a thriving environment. We're seeing, definitely, a trend towards more of that,” he told Denverite. “Retail's actually been the right spot in the investment horizon for a lot of buyers.”

Part of that recovery is tied to new housing projects downtown, like office conversions, that could help replace spending from white-collar workers who haven’t returned since the pandemic.

“This is kind of starting to flip in favor of more residential, in and around the downtown area,” he said. “It’s just a matter of trying to work with retailers that live in both worlds, because you can do some dinner business and you can do some breakfast business, and that is definitely changing before our eyes.”

But, as always in this town, there’s a debate about who those changes are meant to benefit.

V Reeves, a housing advocate with Housekeys Action Network of Denver, said they understand the city thinks it can fund needed services with tax revenue from a property like Pavilions — things like recently slashed budgets for eviction prevention and rental assistance. They just don’t believe it will actually happen.

“They're seeking a means to an end, and saying this is to eventually be able to fund the projects that we actually need. We're spending millions and millions of dollars when we are asking for a fraction of that to address those very things,” they said. “I don't think that that's the economic engine that [Mayor Johnston] is intending it to be. Because we have found, again, trickle-down economics is not an effective solution.”

Denver City Council recently rejected a plan to build affordable housing a few blocks away from Pavilions, because Johnston planned to buy the property with emergency funds that have already been used too often.

Still, city leaders are adamant that projects like the Pavilions are the path forward. Downtown is supposed to be a tax revenue machine — it’s just going through a reimagining.

In the same way Denver had to move on from the days of the mighty department store, former DURA chief Sue Powers said it will have to find a new identity in this moment of change. She said the risks are worth it.

“It's everybody's responsibility now to step up and say, ‘We value our downtown. And it won't look like it did 10 years ago. But there’s a really important historical role that it's played, and it's an important part of our economy, so let's figure out how to fix it,’” she said. “I don't think there's a choice in this community, any more than there was in 1987, to let downtown die. That's just not an option. Not an option.”

The Denver City Council hasn’t yet set a date to consider the plan.

Correction: This article has been updated to reflect that Glenn Mueller was a real estate professor at the University of Denver, not economics, and that Bill Mosher led the Downtown Denver Partnership for one decade, not two.