Your chances of being struck by lightning are higher in Colorado than in nearly any other part of the country, even though parts of the South get way more lightning every year.

Lightning injured 38 people and killed one woman in Colorado last year, the highest combined total the state has seen since at least the 1980s. For the Colorado Lightning Data Center, each of those strikes is a mystery to be solved.

"There's still a lot we don't know about lightning," says storm chaser Carl Swanson.

"It's fundamentally unpredictable," adds Steven Clark, a forensic meteorologist.

But we know a hell of a lot more than we used to.

Clark and Swanson are members of the center, a group of meteorologists, physicians and weather buffs that meets at St. Anthony's Hospital in Lakewood.

After a strike injures or kills someone, the group and its international membership try to reconstruct exactly what happened.

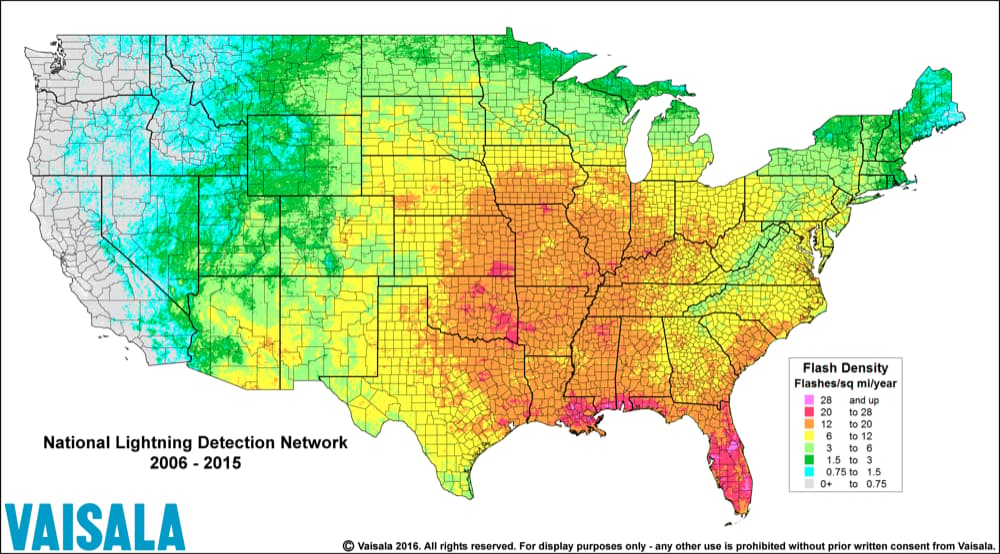

Often, they can pinpoint where and when lightning struck. Seriously. Networks of lightning sensors, such as Vaisala's National Lightning Detection Network, are constantly monitoring the skies for lightning's radio signature, logging each strike into databases.

The data and the researchers together have produced some pretty interesting stuff, but first let's talk safety:

- Study the weather patterns of any place you'll be doing extended outdoor activities. On the Front Range's higher mountains, that often means you should be descending by noon.

- Seek shelter immediately when you hear thunder or spot a storm. Lightning can strike far in advance of the thunderhead.

- If you're stuck in the open with no chance to make tree line, shelter in the lowest possible place, crouch on the balls of your feet, cover your ears and minimize contact with the ground. In this situation, it's best to stay away from isolated trees and rocks.

Now, here's what we know about where and why lightning strikes.

Colorado gets relatively little lightning per year, but that doesn't make us safer.

Lightning-prone spots clustered around Pikes Peak are merely average for the Midwest and parts of the South. Yet those relatively few strikes do a lot of damage in Colorado.

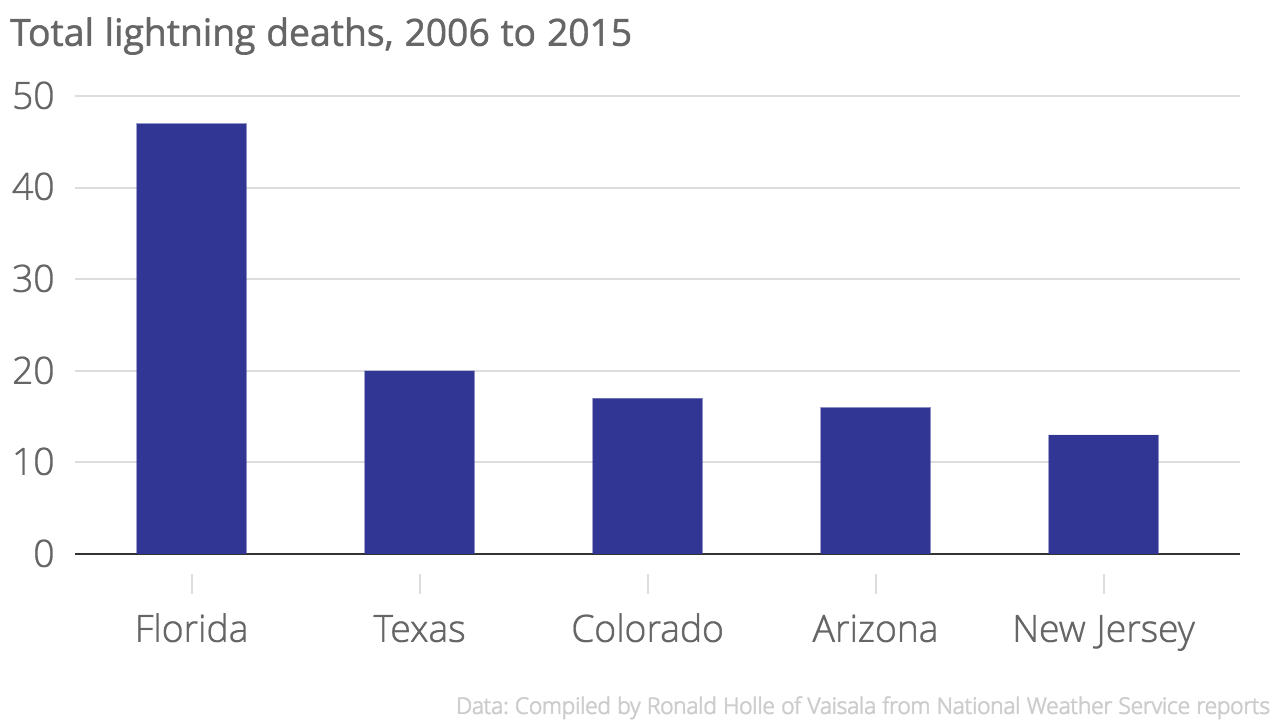

Adjust those numbers for population and you'll find that Colorado's lightning is particularly deadly, with about 0.33 deaths per million residents, second only to Wyoming by that measure.

So, if Florida has lots of people and lightning, why are Coloradans struck at higher rates?

It's worth repeating: High, open and elevated spaces are dangerous during storms.

Now add to that the fact that Colorado's lightning tends to cluster on accessible Front Range mountains during prime hiking season.

Last year's lightning death in Colorado – a young, newlywed woman – happened on Mount Yale. Fatalities in 2014 similarly happened on a hiking trail and in a Rocky Mountain National Park parking lot.

The peak months for Colorado lightning, as shown by lightning sensors, are between May and November.

OK, enough data.

Victims of lightning strikes very often see the storm that hits them. The problem is that they underestimate its power.

Every few months, the Colorado Lightning Data Center will bring in a victim of a strike and try to reconstruct what happened. The same theme emerges again and again at their meetings:

- "She could have sworn that the storms were much farther away than they really were."

- "The satellite imagery shows the clouds were not all that intense, but they were right in the vicinity of where he was."

- "They did not perceive these storms to be very strong."

And each of those strikes has the potential to leave long-lasting injuries, including permanent neurological impairment.

Any one person's chances of being struck are pretty low overall – but in the face of something so unpredictable, maybe it's best to play safer odds.

Correction: This story was updated on June 20 with the correct name of the Colorado Lightning Data Center.