We recently received a call from a resident of the Ballpark neighborhood. She wanted to respond to comments previously published in Denverite about homelessness following an assault reported in her area.

By Susan Dean

Many people, especially new residents, have complained about Denver’s homeless, but few seem aware either of the complex causes of the problem or of the potential for a massive expansion of that population within a few years.

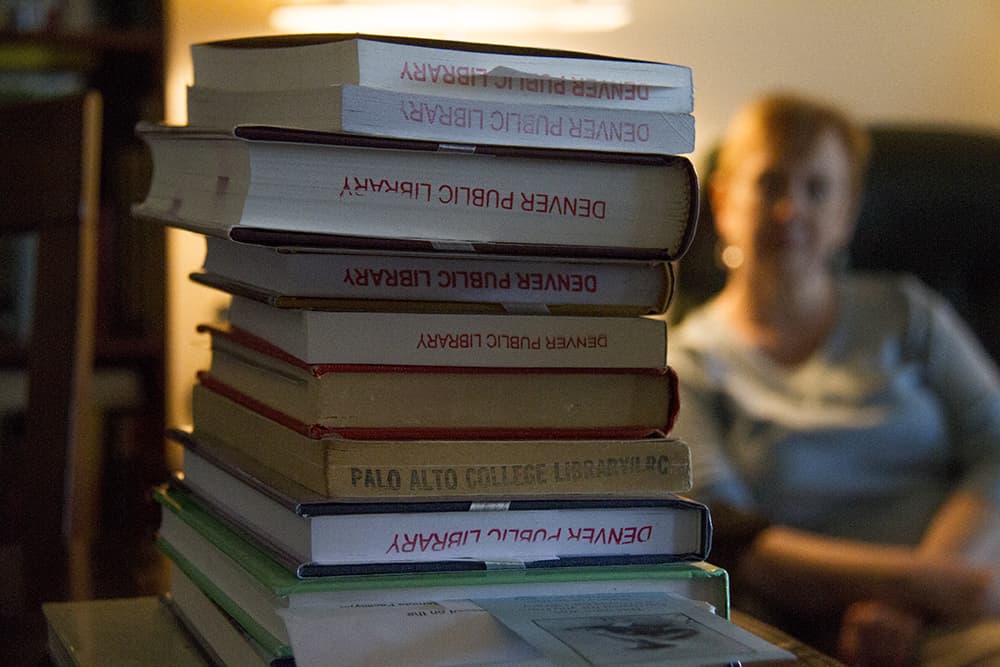

I am a retired librarian and a Denver native whose family has lived here for nearly a hundred years. The specter of homelessness is always with me, even though I have worked most of my life. My retirement funds were swallowed up by medical bills for illness and an injury. I was terminated from my last position for a workplace injury that has left me in chronic pain. I now live entirely on Social Security.

What does that mean?

It means that activities most people take for granted are out of the question for me. I never go out for a meal or for coffee or to a movie unless my generous friends take me. It means I can’t afford a car, so shopping — or going anywhere with Denver’s inadequate public transportation system — is difficult unless friends take me. It means that, no matter how carefully I budget, I can have no money at all in the week before my next payment. Some residents of my building receive surplus food packages, and I am often dependent on the items they do not want and place in the building’s free box. I was thrilled to find two large boxes of corn flakes there a few days ago. My income is “too high” to get those packages myself.

It means that I am absolutely dependent on Section 8 housing for a place to live. My building was low-income senior housing for over 40 years, but that recently changed, and most of the units became market-rate apartments. Now those of us who still have Section 8 vouchers are being encouraged to seek other housing because of possible serious structural issues in the building. We are being given help in negotiating this process, but it can take two to three years to reach the top of a Section 8 waiting list. There is no guarantee that I will find a new home before leaving becomes unavoidable.

Living on Social Security means that I can’t receive the health care I need. Although I have Medicare, my income is too high for Medicaid. Medicare does not cover dentistry, and I desperately need major dental work. I also can’t afford treatment that would make my chronic pain more bearable; the co-pay is simply beyond my resources. I pay a $104.90 Medicare premium every month. My income is too high to have that premium waived as it is for lower-income recipients. I have had to change doctors nearly every year as the co-pays for Medicare Supplement plans keep rising. I’m lucky to have had the same doctor for the last two years, but my plan’s co-pays are tripling for 2017. I will need to either find a new plan and physician or pay three times as much for basic services. And, of course, there was no Social Security COLA (cost of living adjustment) this year, and there will be none next year.

The neighborhood now known as Coors Field was Denver’s skid row for many decades. Because the land was inexpensive, a number of low-income apartments were built here starting in the 1970s. Unfortunately, the neighborhood is now the center of luxurious new developments created largely to serve a well-off population of new residents from other states. People who have lived here for many years are being forced to find new housing, a virtually impossible task given our incomes. To make the problem worse, high-priced new development is not being offset by the creation of low-income housing elsewhere in the city. New residents who complain about the homeless in Denver need to realize the extent to which they are contributing to the problem.

Contrary to public perception, homelessness is not always the result of laziness, addiction or weakness of character. It can happen to anyone, and an illness, job loss or injury can set even the most seemingly secure individual on the road to poverty. Because the senior population is expected to double in the next decades and because so many of those facing retirement in the near future lost significant portions of their pension savings in the last recession, Denver -- and the country as a whole -- may soon see a large influx of elderly homeless on its streets. How we are treated — whether with compassion and practical help or with insults and vilification — will say a great deal about the moral standards of our country.