It's nearly midday at Suntastic Fresh produce in Frederick, and an assembly line full of workers are busy sorting through fresh tomatoes. Virtually everything that makes it this far down the conveyor belt is ready to eat, but 10 percent of it, as much as 12,000 pounds of product every day, could very well be thrown out. And that's just for this one facility.

Produce can be ugly. Yellow peppers can look a little too green, tomatoes can have slight bruising, squash might be a little too big or a little too small. While beauty might be in the eye of the beholder, commercial grocery stores have objective specifications all their products must meet. Those pounds of produce that Suntastic removes from its assembly line just aren't pretty enough.

"Throwing food away every single day is sad," says operations manager Nolan Smith. "There’s a lot of hungry people out there."

But Smith won't be sad today. He put a call out to We Don't Waste, a Denver-area nonprofit that will help clear out his rejects. When Tim Sanford and Dana Van Daele show up with the truck, there are three pallets of vegetables waiting for them. All of it will be transported to metro area food pantries and homeless shelters within a matter of hours. That, in turn, helps another Denver problem: food insecurity.

It's not just a question of supply and demand. Sanford, who's worked in food pantries for years, says it's an endless logistical puzzle to find and fill needs across town with an ever-changing arsenal of food.

Whether it's a thousand hot dogs left over after a Broncos game, boxes of ugly vegetables or a pallet of bacon rejected by Jimmy Johns because it was the wrong flavor, Sanford and Van Daele will load it up if it's still good.

"We don't care if its maple-cured, hickory-smoked or uncured," he says with a twang.

We Don't Waste was founded in 2009.

Ex-attorney Arlan Preblud was bothered both by waste and hunger and had an idea that one problem might fix the other. He started We Don't Waste in his Volvo.

"If you had a loaf of bread, I was willing to take that," Preblud says. "I didn’t know how it was going to work."

Preblud's vision has grown by leaps and bounds, from the Volvo to an Econovan to a small fleet of trucks. The organization just moved into a shiny new facility off I-25.

We Don't Waste's 2016 annual report states they increased their distribution 17 fold between 2014 and 2016, from about $2 million to almost $33 million worth of food rescued each year. Their new facility offers even more potential now that they have space for vertical storage and coolers.

Preblud and his team don't pick up loaves of bread any more. These days they're bent on efficiency.

"It’s economy of scale," he says. "You can’t take a 15-foot truck and stop and pick up two pans of lasagna.”

There's plenty of idle food to go around.

Even if We Don't Waste is leaving a few pans of pasta on the table, they still fill their trucks on a regular basis. In fact, there's more supply than they can handle.

A 2017 report by the Natural Resources Defense Council says Americans throw out 400 pounds of food per person per year. The report is based on a research paper that estimates we waste 40 percent of all available food in the country. That's counting unused corn, corn starch and corn chips, in any stage of production.

Most of the waste is residential garbage, stuff you'd might rather compost than reuse, but about a tenth of food losses come from commercial distribution, usually prepackaged in bulk and ready to eat. That's We Don't Waste's sweet spot.

But recovering the food is just one piece of the puzzle.

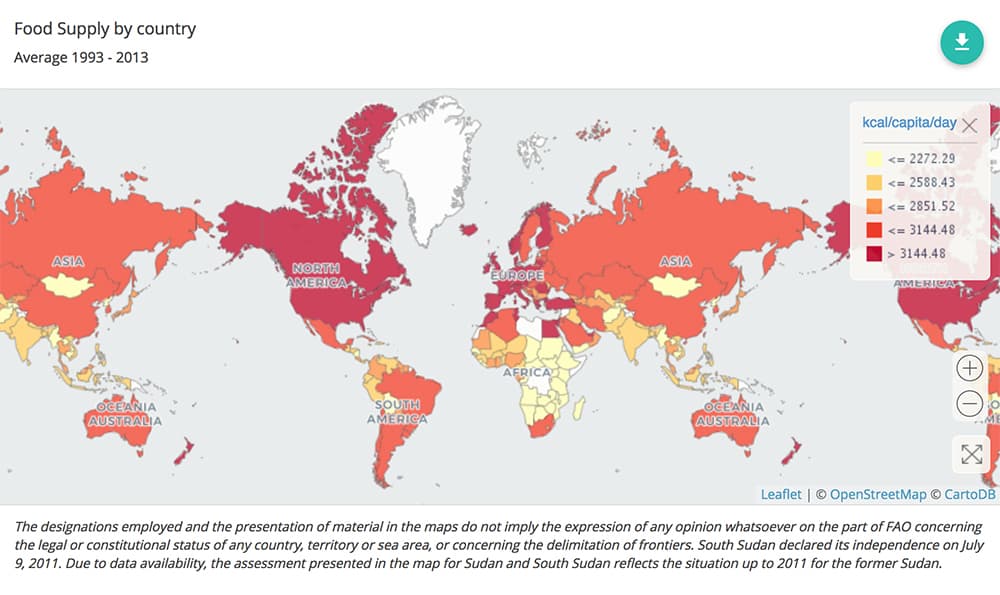

An analysis by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization ranks the U.S. as one of the countries most flush with food per capita. We've got more than 3,000 calories available per person per day (more than even your average teenager needs). Yet one in 10 Coloradans struggles with hunger.

Sanford, director of operations, has worked in food pantries for years and sees this arrangement from multiple perspectives. While he says We Don't Waste could fill twice as many trucks, there wouldn't necessarily be places to put it.

"The underlying problem is not recovery," he says, but rather the ability of food pantries or shelters to accept it fast enough.

Food pantries have been on the decline in Denver in recent years. While some authorities have said fewer pantries means more efficiency across the board, Sanford thinks a lot more capacity could be filled.

All that said, an individual NRDC look at Denver found that we're doing pretty well compared to other cities.

"Denver is fortunate to have a fairly extensive food rescue system," the report says. We already salvage up 70 percent of all grocery waste, we fill a greater portion of our hunger needs with waste than New York City or Nashville and our "meal gap" is overall smaller than those two cities.

Groups like We Don't Waste, with their trucks, and Denver Food Rescue, which now delivers groceries with their bicycle fleet, have clearly made an impact.

Nationally, grocery stores are also getting on board, and there are a slew of pilot projects from Walmart to Whole Foods that have tried to sell ugly vegetables. But many of these are tentative trials, a sign stores know some buyers just want the cream of the crop.

"Their clientele expects perfect, perfect food," Sanford says.

If we're going to be so picky about what we buy, at least we have ways to get that would-be waste into the hands of someone who can use it.