Denver is changing, and the resulting instability that has rippled through its neighborhoods played a role in teacher strikes that grabbed Denver's attention and national headlines this week. Unlike the statewide walkout last April, this strike focused specifically on Denver's teachers and how they were paid.

Tensions have simmered since the ProComp pay system was implemented in 2015.

It was initially held up as a new, progressive model before district employees began to sour on the model. When anger with ProComp came to a head this year, the Denver Classroom Teachers Association went on strike, putting more pressure on discussions with the district. The union wanted to do away with an emphasis on bonus pay and instead secure higher base wages.

Teachers have said those bonuses -- the bonuses for working at a school with higher need and the bonuses for working at a school where kids are performing particularly well -- were unreliable partly because of larger changes playing out as a result of growth and rising rents.

Now that the union has won higher base wages and a more transparent system around them, teachers and union reps have said that instability has been neutralized.

During the strike, teachers around the district repeatedly raised a specific concern with the system: If neighborhoods surrounding poorer schools gentrify and more affluent kids are enrolled, some bonuses associated with lower incomes might have disappeared. On the other hand, teachers who receive bonuses for high achievement in their classrooms feared that students' grades could drop if their families are displaced due to rising living costs, which could threaten good-grade incentives.

Here's what just changed because of the strike.

In the old pay system, there were multiple bonuses tied to at-risk students, but we'll focus on these two:

Before:

- Hard-To-Serve, which granted teachers an annual $2,738 bonus under the old pay regime. Elementary schools got this designation if more than 92 percent of students qualify for FRL. For middle schools, the threshold was 85 percent. For high schools it was 75 percent.

- Title I, a federal designation that granted teachers an annual $1,540 bonus under the old system. A school still gets this designation if more than 60 percent of students qualify for free reduced lunch (FRL). If that percentage of students drops for more than two years in a row, the school loses that status.

After:

- Hard-To-Serve no longer exists. A spokesperson for the district said that was done to simplify things, so funding could go instead to two "poverty incentives," Title I and "Highest Priority."

- Teachers at Title I schools now get annual $2,000 bonuses. It's an increase even though poverty initiative funding dropped $1.8 million district wide as a result of the deal.

Before the strike, teachers relied more heavily on these two bonuses, and both were dependent on who enrolled in their schools. Now that base pay was bolstered and Hard-To-Serve status will no longer be offered, as a result of the new agreement, the bonuses play a less critical role in teachers' overall compensation.

Title I is still in there, though, and it's still responsible for some degree of volatility, but teachers say it now behaves more like a bonus should.

But before a deal was struck, rising rent and resulting displacement intensified how these incentives rocked teachers' livelihoods.

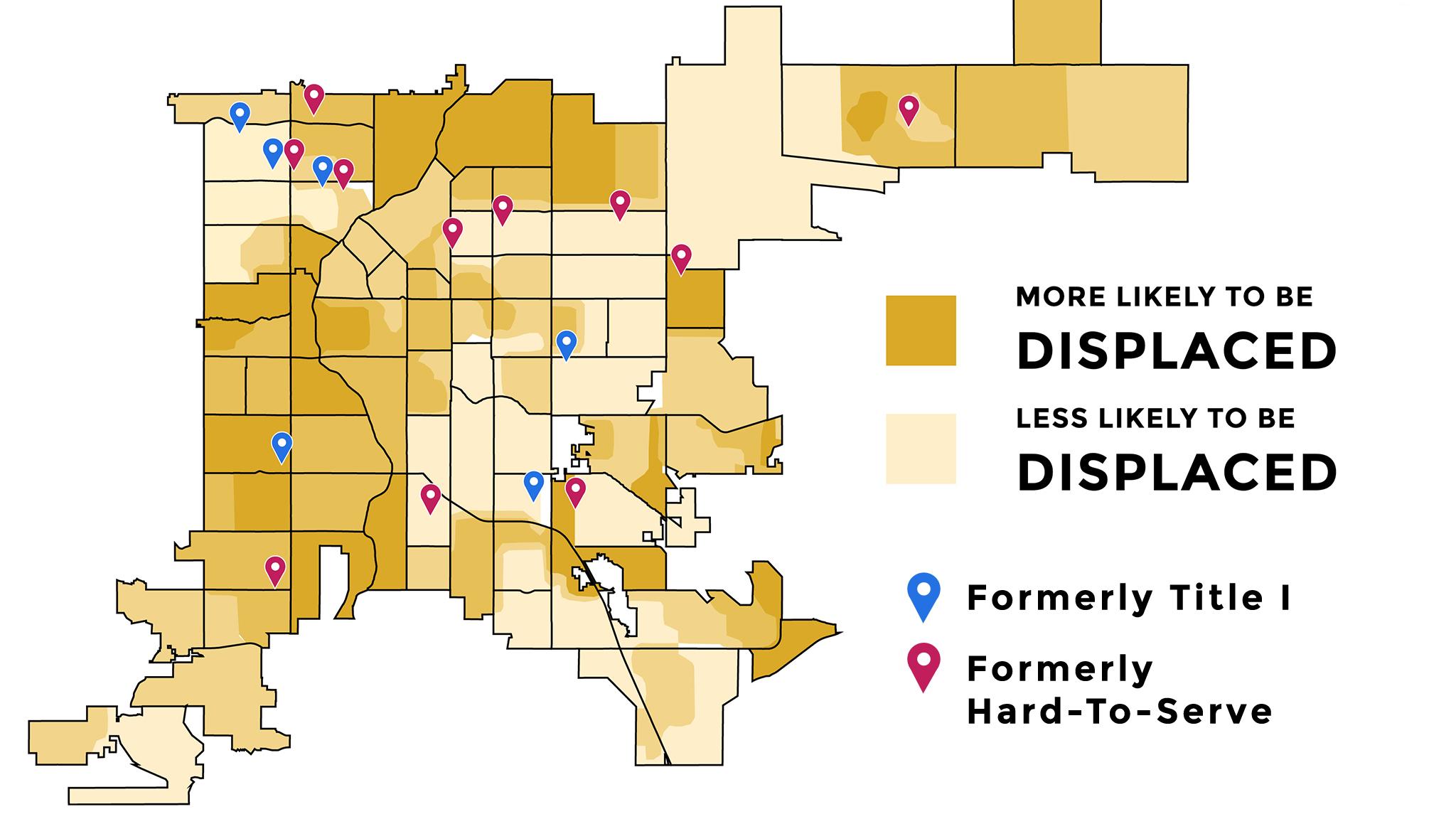

Since the 2016-2017 school year, six schools that are still open and were previously designated as Title I have lost that designation. Since the 2014-2015 school year, 11 schools that are still open and were previously designated as Hard-To-Serve lost that designation.

Next year, a spokesperson for Denver Public Schools said, North High School would have been lowered from Hard-To-Serve to Title I. South High School will lose its Title I status.

Not all of these schools owe these changes to gentrification - at least one redrew its boundaries in recent years, which shifted its demographics and tipped the scale. But if you look at a map of these schools on top of a recent Blueprint Denver map, you'll see many are located in neighborhoods projected to see greater displacement.

For many striking teachers, this was an obvious trend.

Henry Roman, president of Denver's teachers union and a teacher at Teller Elementary, once worked at Columbian Elementary, which lost its Hard-To-Serve status in 2015. He told Denverite it was definitely the result of changing economic tides in around the Sunnyside school, which he said have been shifting for decades.

"Housing and especially rent has become really expensive," he said, and that played into Columbian's changing demographics and loss of its Hard-To-Serve demographic.

Southwest, northwest and northeast Denver are seeing the most of these changes, he added.

Elise Lucero-Frederick, an English teacher at Lincoln High School in southwest Harvey Park, lives near her school and said her neighborhood is undoubtedly changing. One sign: her home picked up about $100,000 in value since she bought it, despite the fact that "we haven't done anything to it."

Lincoln was listed as Hard-To-Serve. Even though that designation will no longer be used, it's still listed as "Highest Priority," which is a status decided by a board of district and union leaders and is limited to 30 schools.

Lucero-Frederick said most of her new neighbors' kids are still pretty young, if they have kids at all, so demographic change at Lincoln is likely to be some years off.

"It would be a couple years," she said. "It's not like it will happen overnight, as the neighborhood continues to gentrify."

But for Godsman Elementary, not far from Lincoln in Ruby Hill, change is already taking root. Godsman was also designated Hard-To-Serve, and will now just be listed as Title I.

"We're getting young, hipster couples who don't have children, they have dogs, and so our percentage is falling," 5th grade teacher Rachel Sandoval said. The newcomers who do have kids are not likely to qualify for free lunch and, she continued, "We're going to lose part of that unpredictable bonus." They would have, anyway, before the strike.

School populations overall were projected to fall this year as a result of gentrification. Sandoval estimated Godsman lost about 50 kids annually over the last few years.

Heather Abreu was the only teacher at Colfax Elementary who did not strike. She said she couldn't afford to miss a paycheck, although she agreed with her colleagues' mission. Around Sloan's Lake, she said, a lot of students and families have moved as rents have risen. Colfax was also a Hard-To-Serve school.

"As far as the demographics of our students, it's greatly changing," she said. "I've noticed a lot in the last year I've had to say goodbye to students because they can't afford to live in the area."

As the picket line dissolved on Tuesday outside of South High School, Moira Casados Cassidy, who teaches English and English Learners, told Denverite that federal politics are also coming into play for her school. South has a special program for refugee students, and the number of those students have dropped since the Trump administration drastically cut refugee admittances. She estimated the school's newcomer class dropped from 20 to six. Her colleague, English teacher Kurt Scheumann, added that South's freshman class was "as white" as he's "ever seen."

Casados Cassidy said the changing proportion of actual low-income students might not be that large, but it was still enough to flip the ratio. The percentage of kids eligible for free or reduced lunch at South hovered above 60 percent between 2014 and 2016, but dropped to 59 in the 2017-2018 school year and dropped further to 52 percent this year.

Since South is projected to lose its Title I status, she and Scheumann are poised to lose the $2,000 bonus that would have been tacked onto their paychecks over the next year.

"We may lose the bonus, but it's not meaningfully changing our population," she said. "That's the thing that's frustrating about it. We still have a lot of students living in poverty and who have experienced trauma, et cetera, although the population might have changed by a small percent."

Because these bonuses were tied to economic status, many of the teachers we spoke to said their paychecks were tied to the diversity of their classrooms.

"We're really proud that we have a socio-economically, racially, ethnically integrated school. We're punished under the ProComp system for having an integrated school," Casados Cassidy said of South. The old system, she continued, "Rewards schools that are very segregated economically and racially."

So it was good news when she heard the union won concessions over higher, more predictable base pay. While she declined to say how much her salary will increase as a result, she said it more than covers the soon-dissolving Title I bonus: "It's a game-changing, lifestyle-changing raise."

Since rising housing costs affects teachers, too, Roman said the union's win with the district has put a lot of his colleagues at ease.

"They have one less thing to worry about," he said.

There's another side to this, too, that was less affected by the strike: Displaced students might have a harder time making the grade.

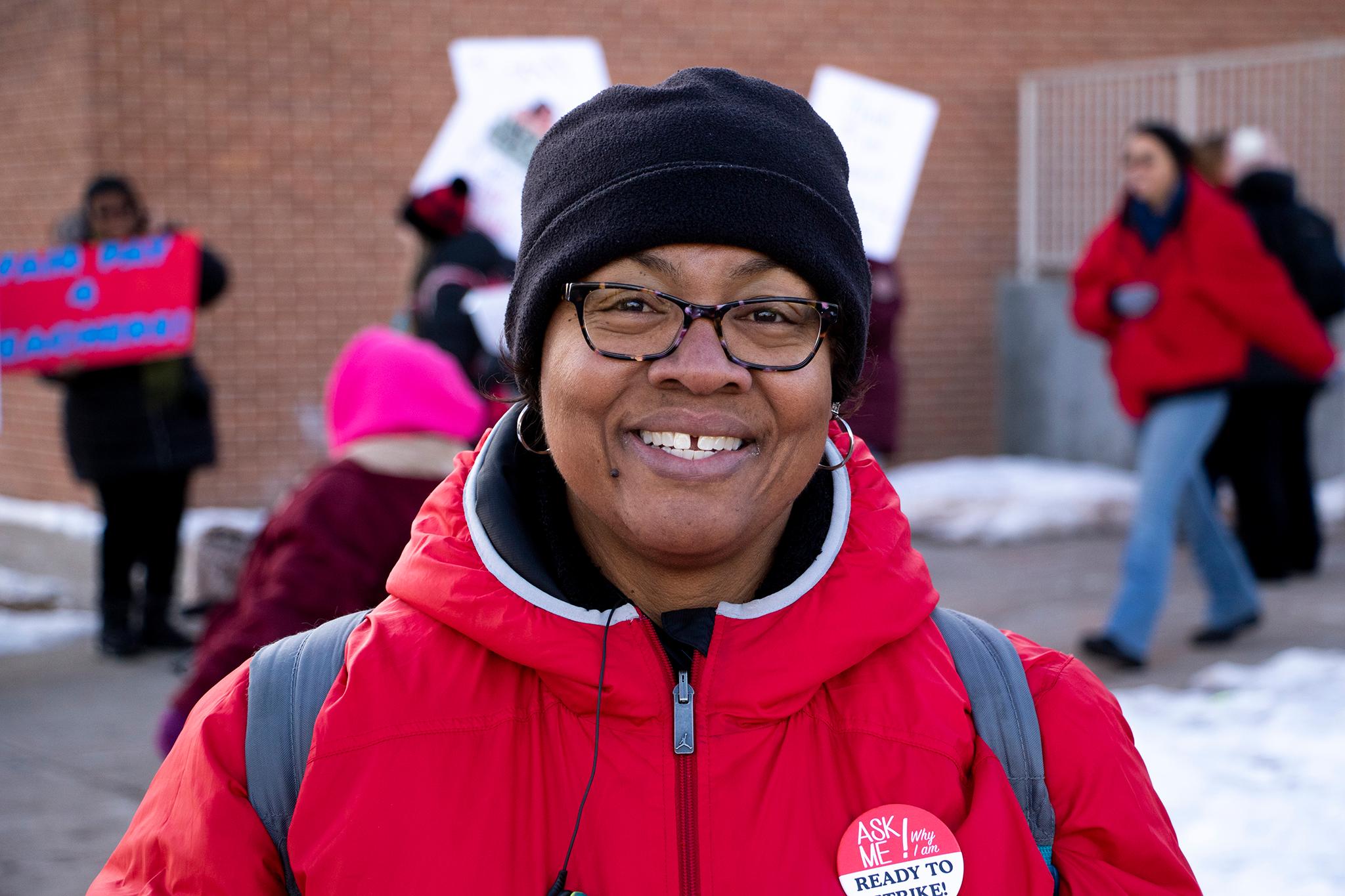

Lynette Hall-Jones, a teacher evaluator and former instructor who has worked at Whittier ECE-8 School for 22 years, said many of her students drive in from all over the city to go to school there. Many of their parents once lived in the neighborhood and attended Whittier themselves. There's still a desire to be a part of the school's community. Since a lot of newcomers to the neighborhood place their kids in other schools, and she feels like Whittier's demographics have stayed relatively stable.

"We have lost a lot of our families," she said, "but we do have families who have always choiced in. They come back. They drive in every day."

Even so, she has noticed small changes in her school's demographics. Whittier is one of those schools that recently lost Hard-To-Serve status.

Students who still live nearby, Hall-Jones said, face "uncertainties" as the neighborhood becomes harder to stay in. Dealing with change can affect kids' ability to focus and score high marks.

Whittier is a "green" school, which means it ranks among the district's best-performing, and there's a separate teacher bonus for that. Hall-Jones said displacement among students could whittle away at their distinguished designation, although she added she and her colleagues work hard to make sure their kids continue to do well.

But this kind of instability is not something the union could address in their negotiations.

"Those are things that are not necessarily within our control," Roman said.

Manasseh Oso, a social studies teacher at Manual High School, said he agrees that the district's bonus system rewarded segregated schools. Manual, like Whittier, is also not on the brink of a gentrified student body.

While many of his students families have been forced to move out of nearby neighborhoods as a result of rising rents, Oso said many kids choose to attend Manual and drive in anyway.

"When I think of destabilization, I think of the fact that gentrification has pushed these kids out of these neighborhoods," he said. "Gentrification is this fist that scatters and then destabilizes the school culture."

Many teachers at Manual were not out striking. The school could face state intervention or even closure if its students don't test well this year, so many of Oso's colleagues remained in their classrooms to keep their kids learning. In addition to changing demographics outside the school, a strike might have played its own role in destabilizing its students.

"The impact of a strike is not the same at Manual as it is at East or South," he said. "We're in a pretty precarious situation."