Here's your semi-regular reminder that real scientists work at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.

Earlier this month, a study co-authored by DMNS arachnologist Paula Cushing was published by the journal "The Science of Nature." The paper, titled "Spiders in space: Orb-web-related behaviour in zero gravity," observes how these critters build ordinary "Charlotte's Web"-style webs in completely new surroundings, devoid of natural conditions like sunlight and gravity.

That's right, a couple of tiny, eight-legged arthropods got to experience zero-G before you did.

Normally, Cushing said, spiders use wind currents to float their first strands of silk into place, then build circular webs off of these foundations. On Earth, the centers of these webs, called "hubs," tend not to be centered and are built in a web's upper half. It's believed this orientation is a survival strategy, since it's easier for spiders to climb down to safety than up.

In space, webs tend to be more symmetrical. Without gravity, spiders have nothing to signal where "up" really is, so they skip this part of the design.

Except, in some of these experiments, researchers realized they did provide a way for spiders to orient themselves. Cushing and her colleagues sent spiders to space twice, once in 2008 and once in 2011. During the second trip, they used a camera system that activated a light in 12-hour cycles. When spiders began building webs during the 12-hour period when lights were on, they tended to build asymmetrical webs that looked more like those found on Earth.

"We conclude that in the absence of gravity, the direction of light can serve as an orientation guide for spiders during web building and when waiting for prey on the hub," the researchers wrote.

You can see a video of the spiders on Youtube.

There's a lot more spun up in these findings than the way light influences spiders in space.

This isn't the first time spiders have left Earth. In the 1970s, researchers sent some to Skylab, the United States' first space station. But that experiment had flaws, Cushing said, particularly because the spiders weren't given food or water to survive.

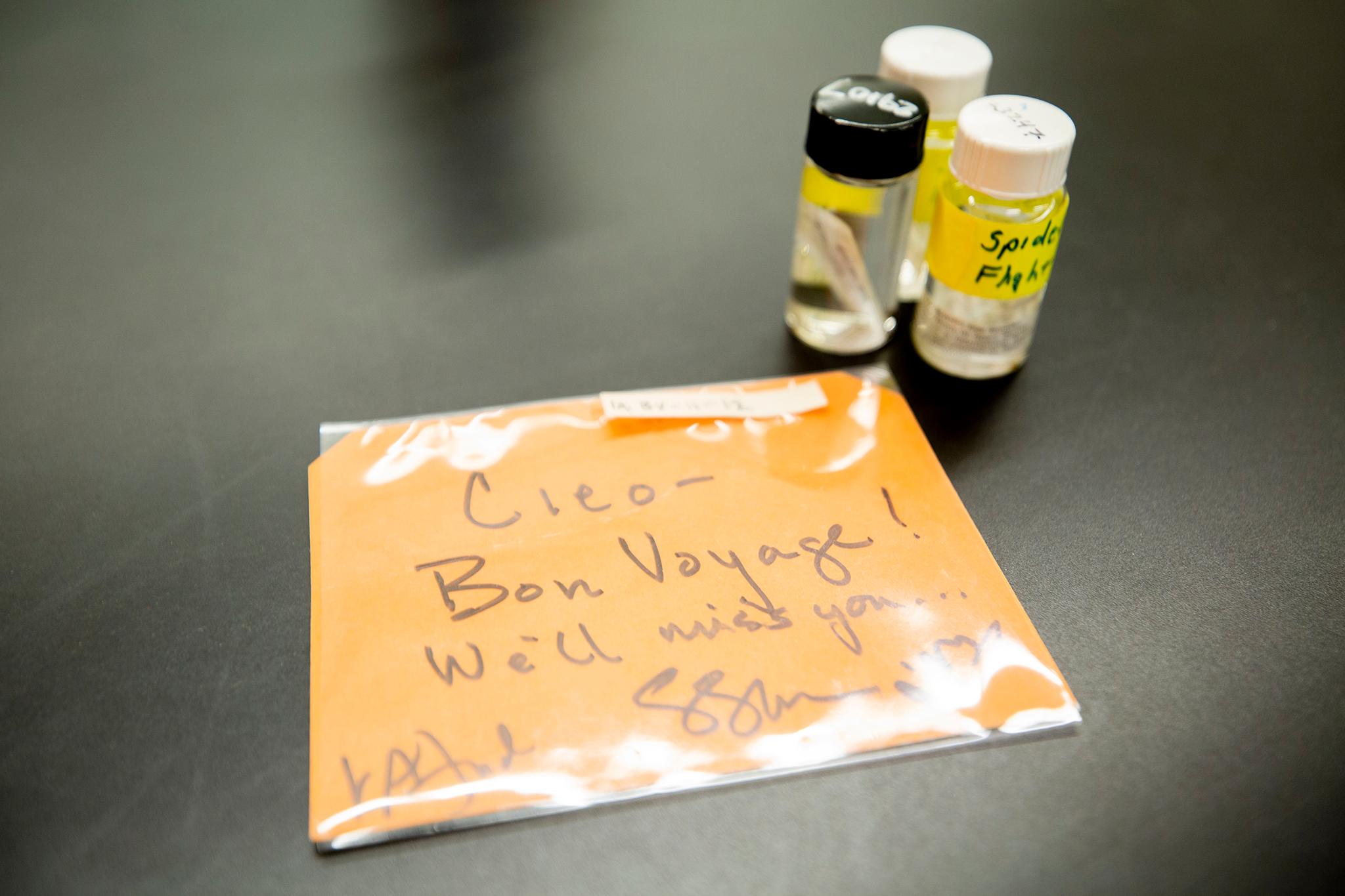

She saw an opportunity to improve upon Skylab's setup when she was approached by BioServe, a Boulder-based company that designs experiments for space, to send spiders back to zero-G. She helped design habitats that would provide sustenance and allow researchers to observe web-making in action. BioServe researcher Stefanie Countryman is also a co-author on the study.

The fact that zero-G webs look different than their Earth counterparts is interesting, Cushing said, because it shows how gravity plays into spiders' work. But it's amazing that they can make webs in space at all.

"It takes them about three days to acclimate to that zero-gravity environment. Up until that point, they just fill the habitat with silk," she said. "It's total disorder. They don't know what's going on, theoretically."

But after three days, spiders begin to figure it out. They learn to walk their first strands across their habitats, and then they begin to weave traps just like they would on Earth.

Spiders' brains are not like those found in mammals. Each has two ganglia of nerve cells that surround their stomach, all packaged compactly inside their heads. These double-brains plug directly into their legs. While it's not known how many brain cells spiders actually have, Cushing said, spiders are considered pretty simple thinkers. And yet, they can adapt to conditions found nowhere on Earth.

"If you think about that, for a tiny animal to be able to have that level of behavioral plasticity, it is amazing," she said. "It's astounding to think about that."

This work adds one more entry into a growing body of research that shows how all kinds of organisms can adapt in space. Experiments growing lettuce, bacteria and fungi in zero-G will help us understand what might happen if (and when) humans begin to live permanently on other plants. Some of these findings will shed light on how our own bodies adapt. Others help paint a picture of how all life manages without Earth's gravitational pull.

"What's exciting is that, more and more, we're getting answers that, yes, organisms, not just humans, are able to adapt to this very different environment," she said. "For bacteria and fungus, that's a little scary because some of them certainly could have health implications."

While Cushing isn't aware of any plans to set spiders loose in any future space colonies, it's clear that they can be very crafty.

"There's a myth that wherever you, are there's a spider within 10 feet of you," Cushing said. "And that's absolutely true."

Their ability to learn and maneuver means they have no problem finding nooks and crannies all around you here on Earth. But before you wince, Cushing said that shouldn't creep us out.

"I think it's our tendency to keep nature 'out there' that triggers our ick response," she said. "It's an irrational response."

The opportunity to study spiders is virtually boundless. While there are about 5,500 species of mammal (class, Mammalia) on Earth, there are more than 48,000 species of spider (order, Araneae) that we know of.