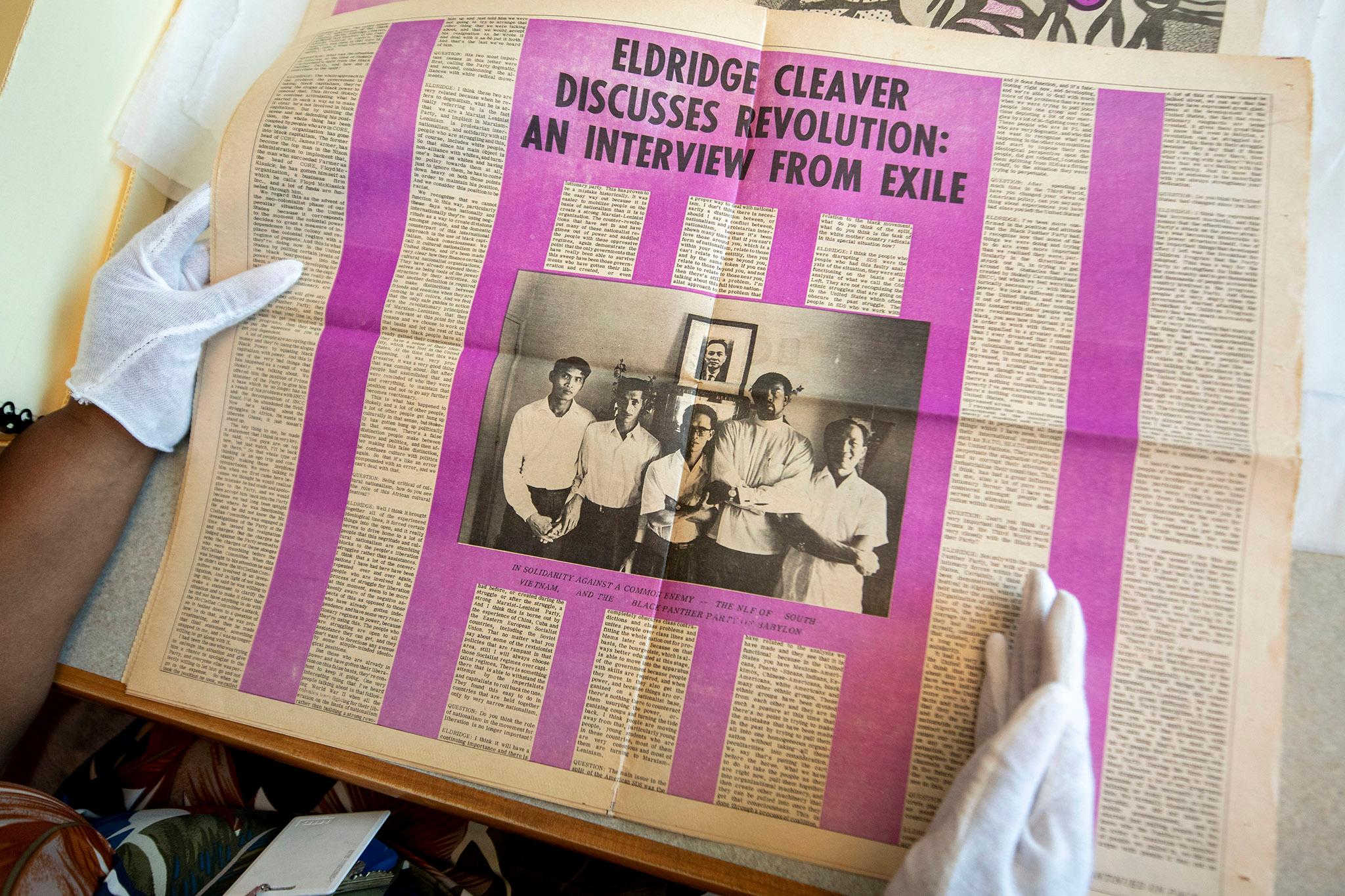

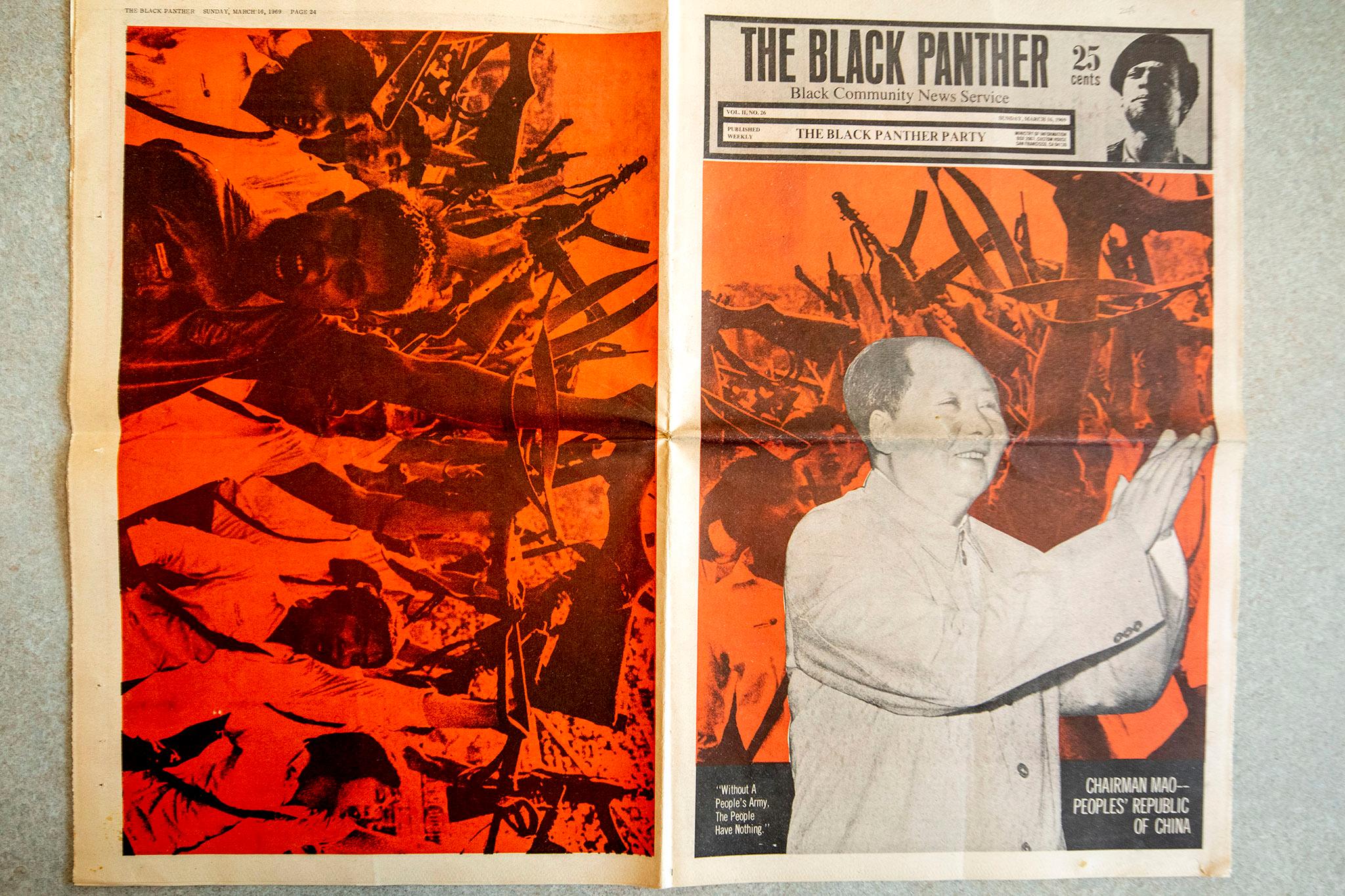

Jameka Lewis, senior librarian at Five Points' Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library, was taken aback when she finally had the opportunity to see the newspapers up close. The Denver Public Library had recently acquired eight rare, pristine issues of the Black Panther Party's official newspaper. Once they were catalogued, boxed up and delivered to her branch, she had an opportunity to slip on a pair of white cotton gloves and run her fingers over their pages.

"We've all taken our turns with them, reading through them and just being in awe of that history," she said. "I was excited because, in my opinion, the Black Panthers are one of the most misunderstood groups that has ever existed."

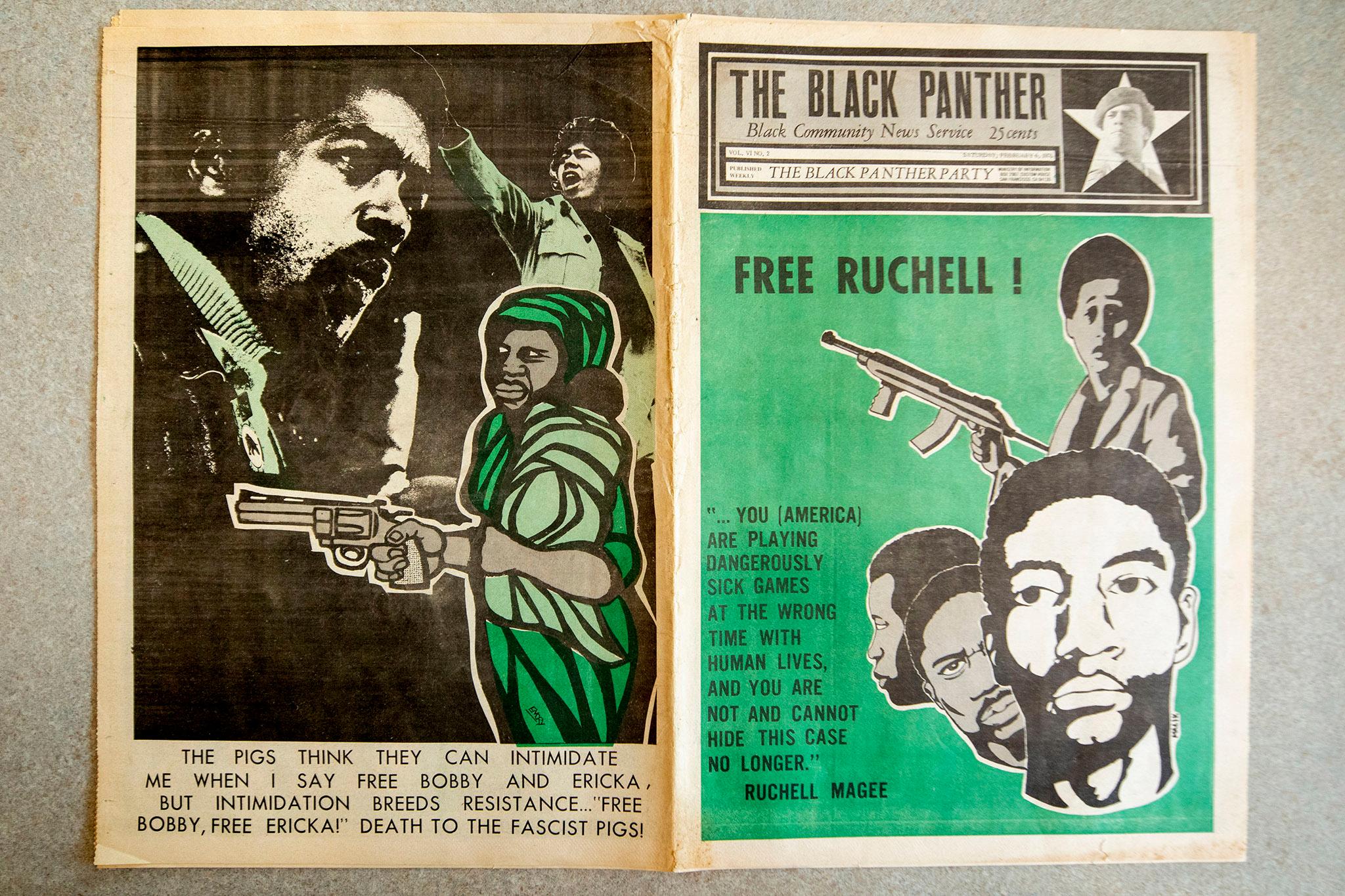

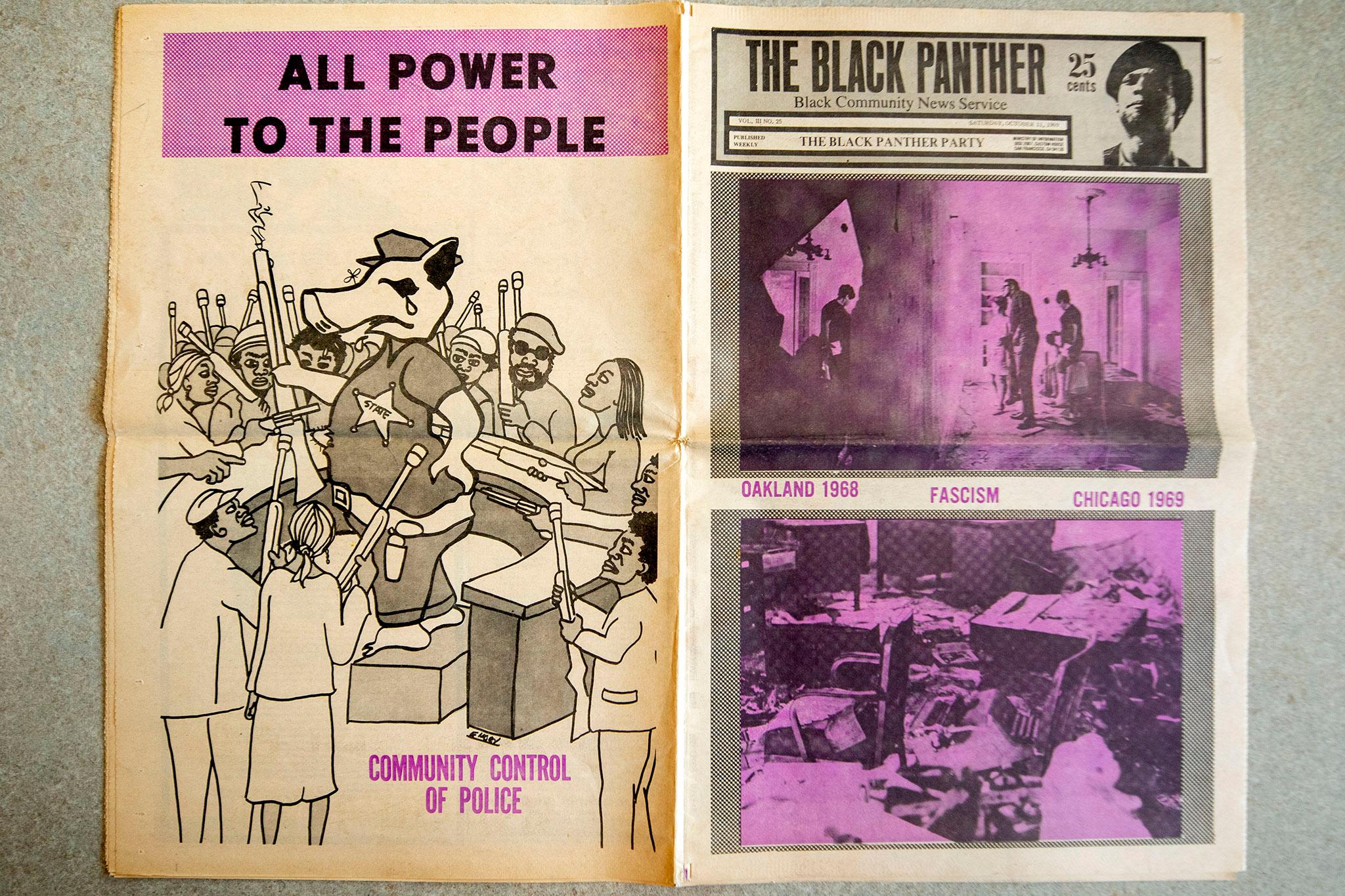

The newspaper was published between 1967 and 1980 and the issues were minted out of California's Bay Area, where the party was founded. DPL purchased the newspapers as part of an effort to add diverse perspectives to their archives.

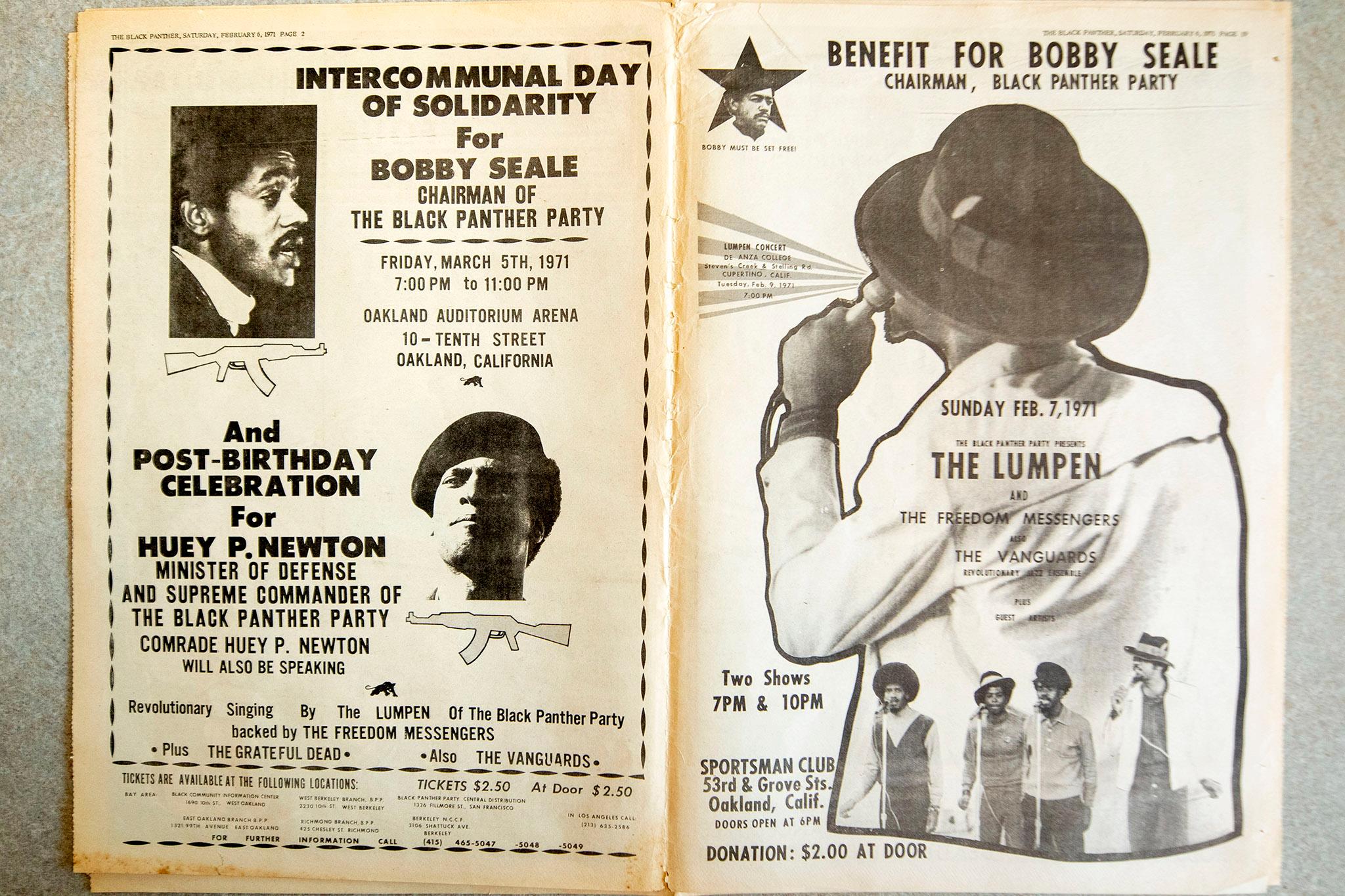

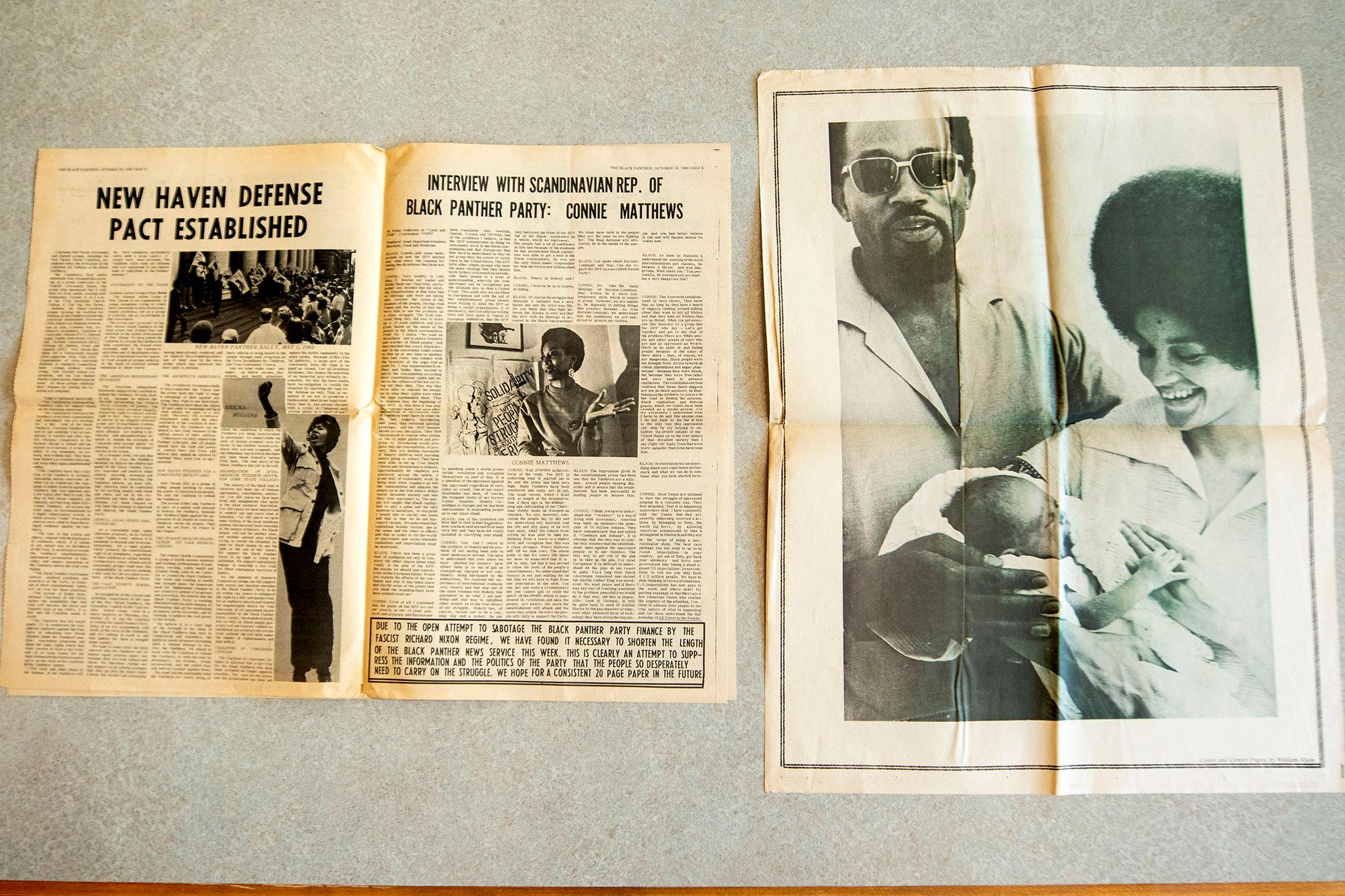

Blair-Caldwell is just one of five research libraries attached to public library systems in the U.S. that focuses on Black history. Since Denver was home to a Black Panther Party chapter, and because the issues focus on the history of the West, Lewis and her colleagues were eager to add the Party's voices to their collection. The pages join a rich array of publications focused on the Black experience in America, including boxes full of photographs from the locally printed Odyssey West magazine and scores of issues of Jet Magazine.

They're happy with just eight copies of The Black Panther, for now, but a library spokesperson wrote to us that "we want more!" Oakland's African American Museum & Library, another of the five public Black history institutions, has 420.

The new additions are an opportunity to read about the party's views and struggles firsthand.

The misunderstanding Lewis mentioned was rooted in fears of Marxist ideology during the cold war, racism and the federal government's deliberate attempts to undermine the Panthers as the organization grew.

"There's just so many misconceptions about the Black Panthers. Oh they were too militant. Their methods were too harsh. They hated white people and they hated the police," she said. "Some of those things are true. They did not really support police, and that was because of what was happening at the time, which mirrors what's happening now. So some of those things are understandable, but to paint them as a terrorist group or as a group that terrorized white people, it's just not true."

Informing the public's perception of the party is a big reason why she's glad Blair-Caldwell can help preserve their ideas, in their own words, for the future.

"These will be used as an educational tool, so that people can't misconstrue what the Panthers stood for," she said. "These papers, these words, are directly from them. And you can't argue with what someone has put out about themselves. How do you refute that? You don't."

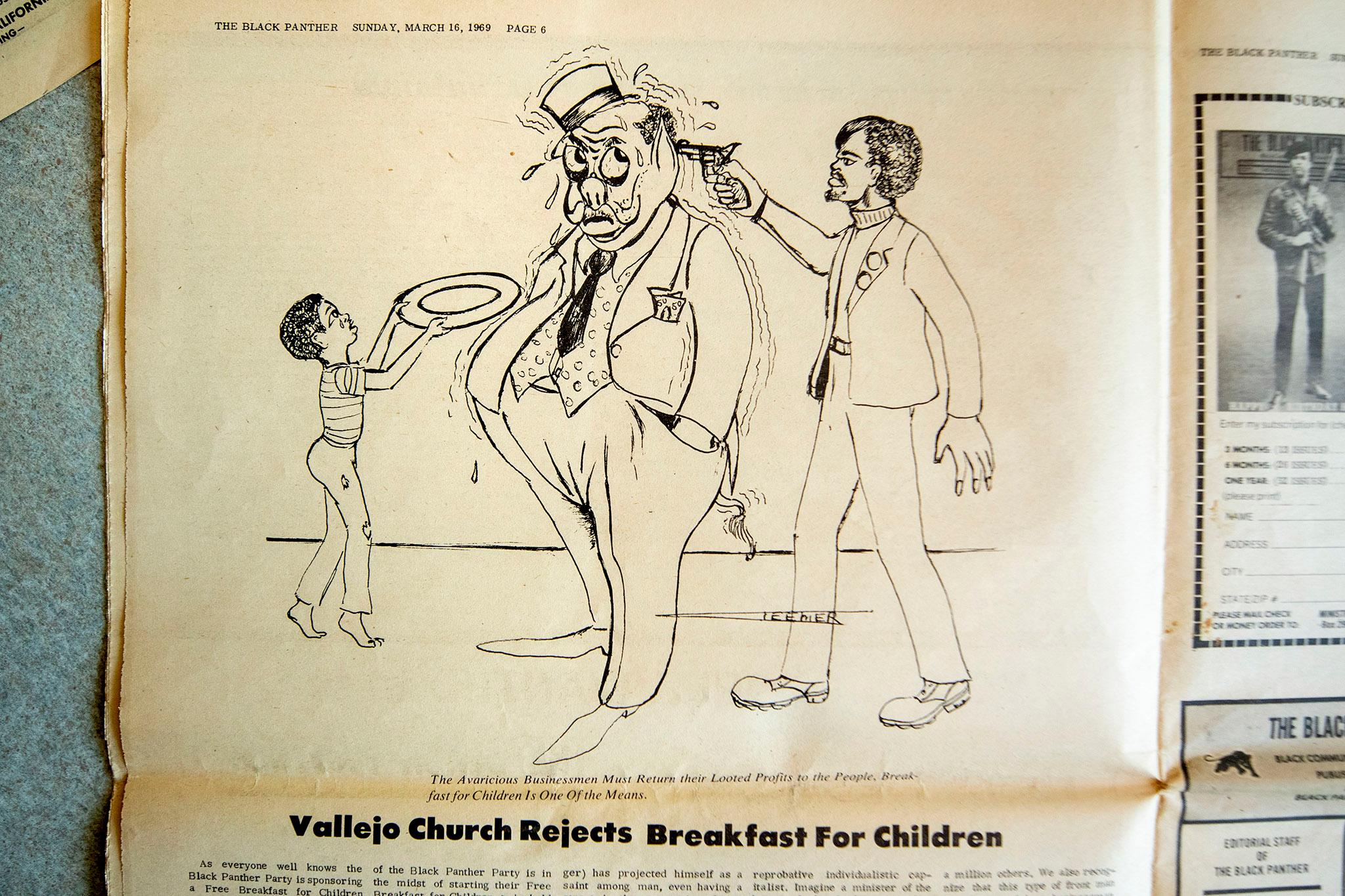

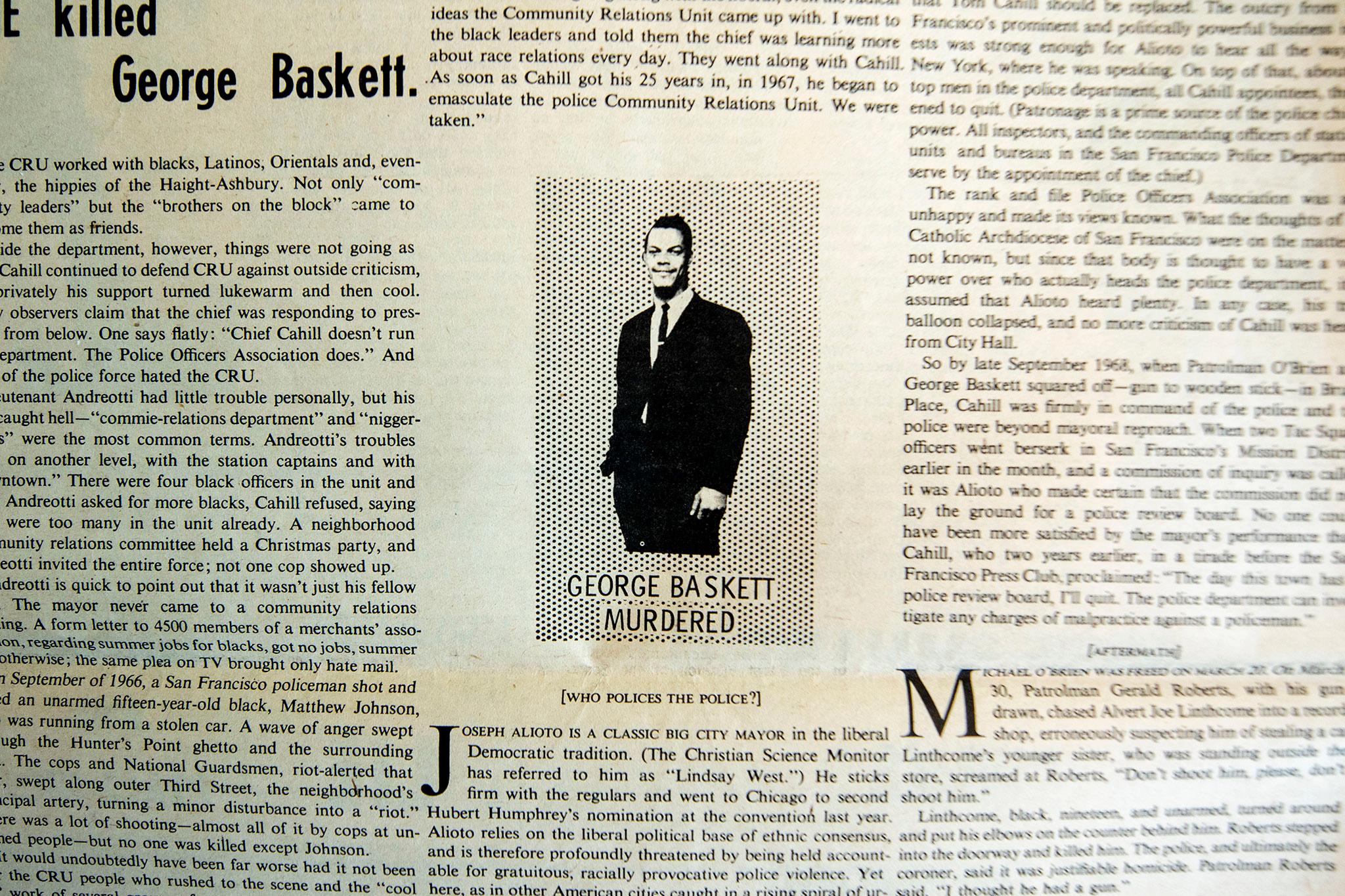

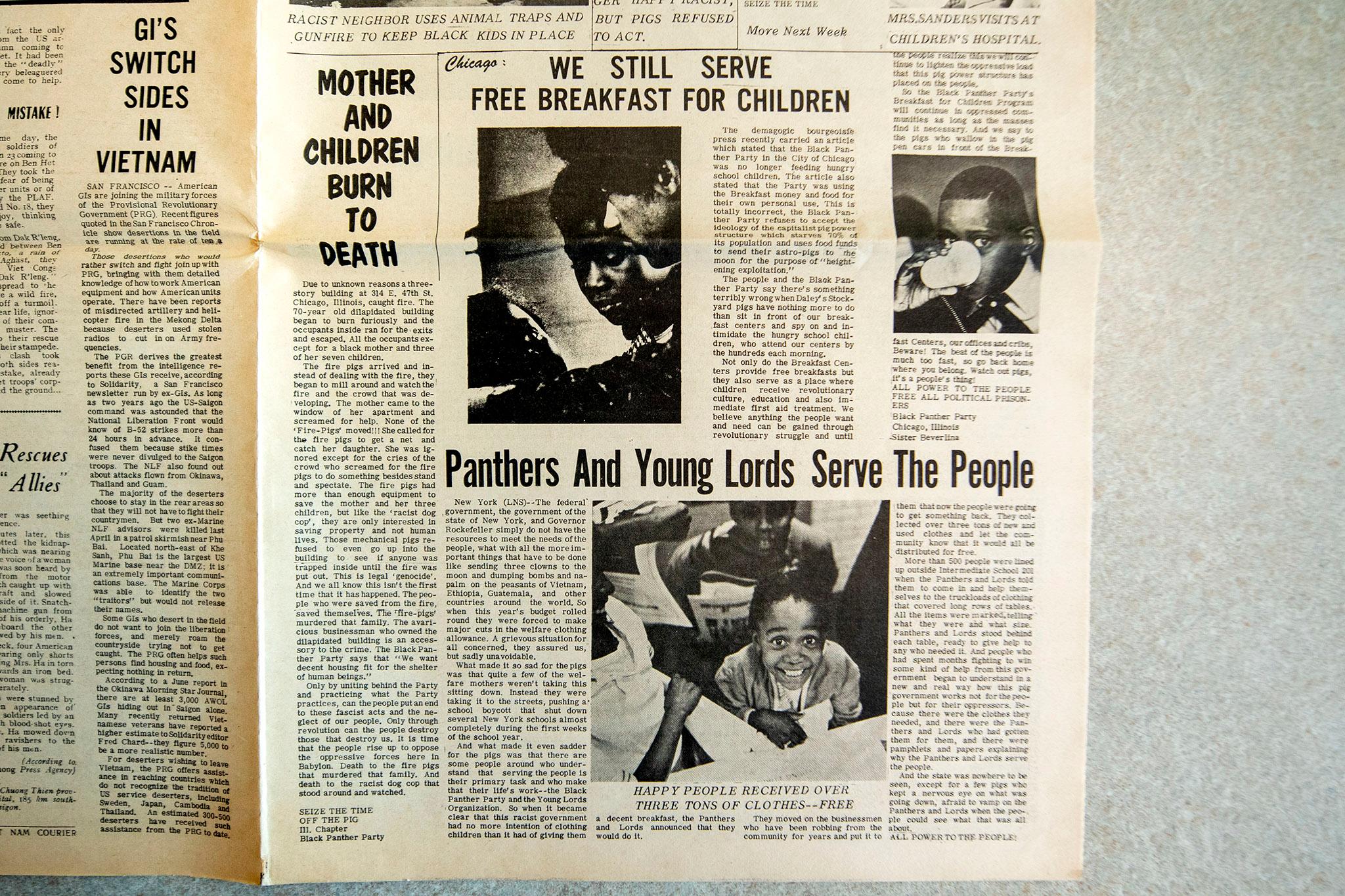

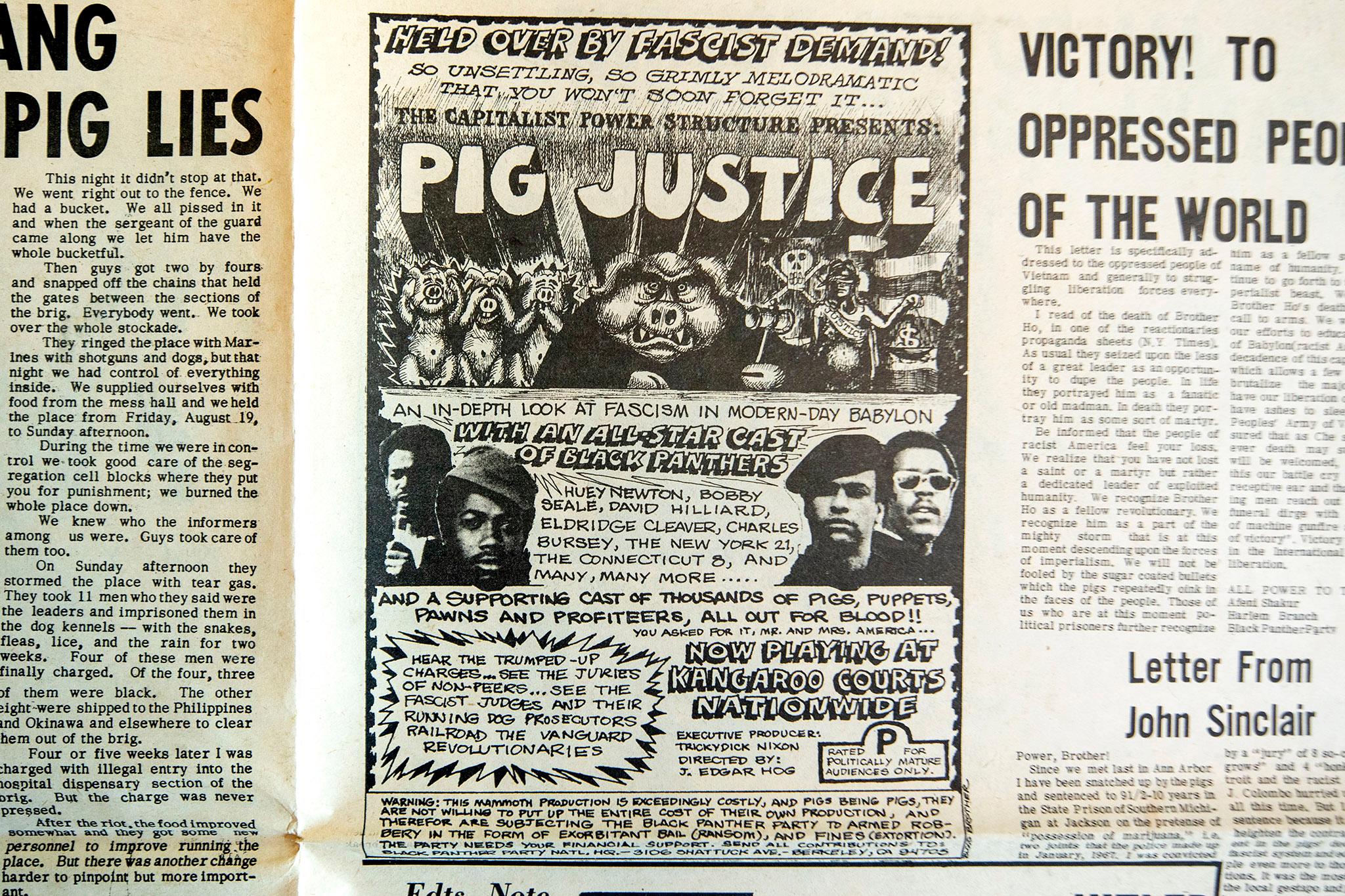

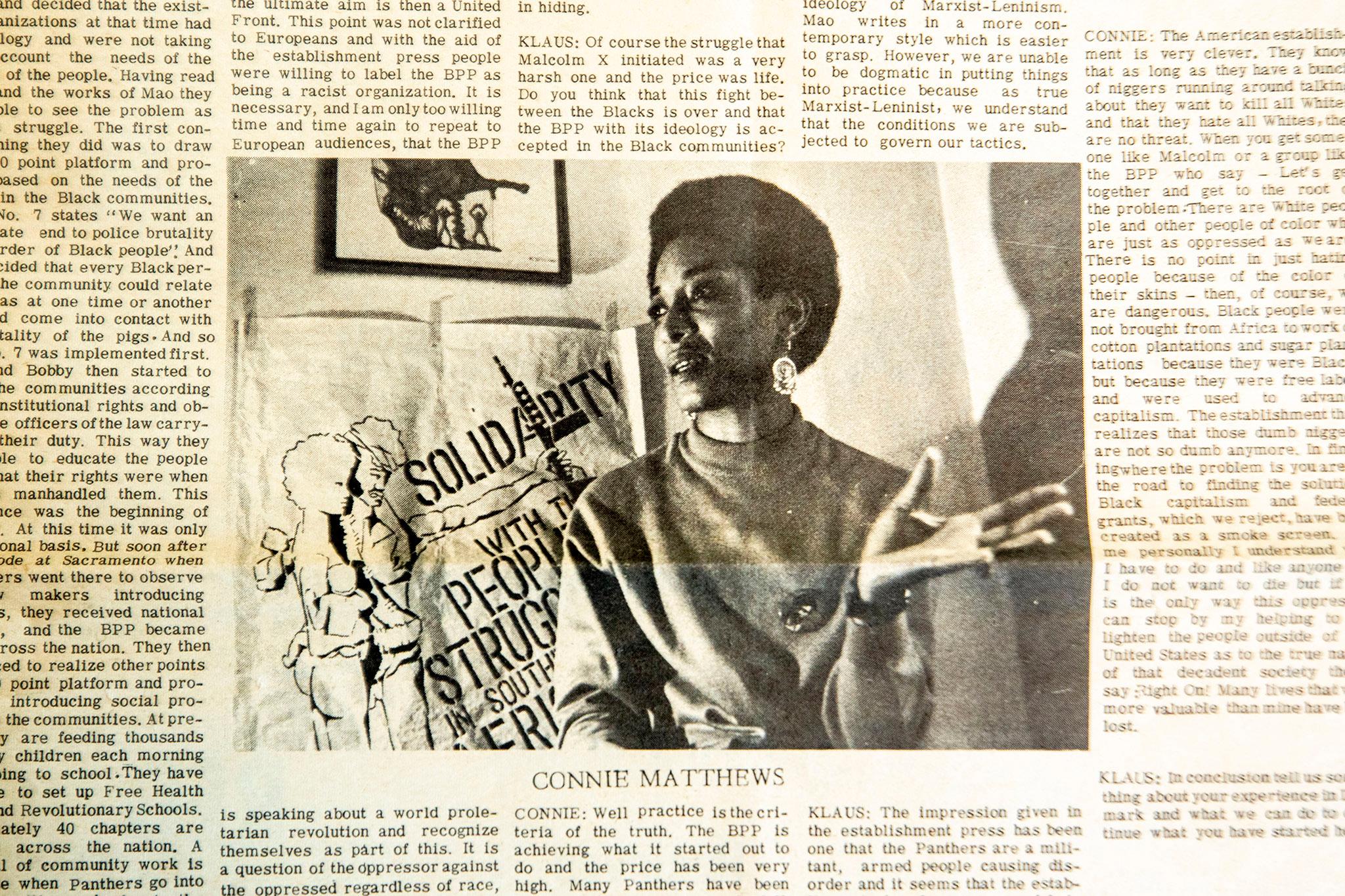

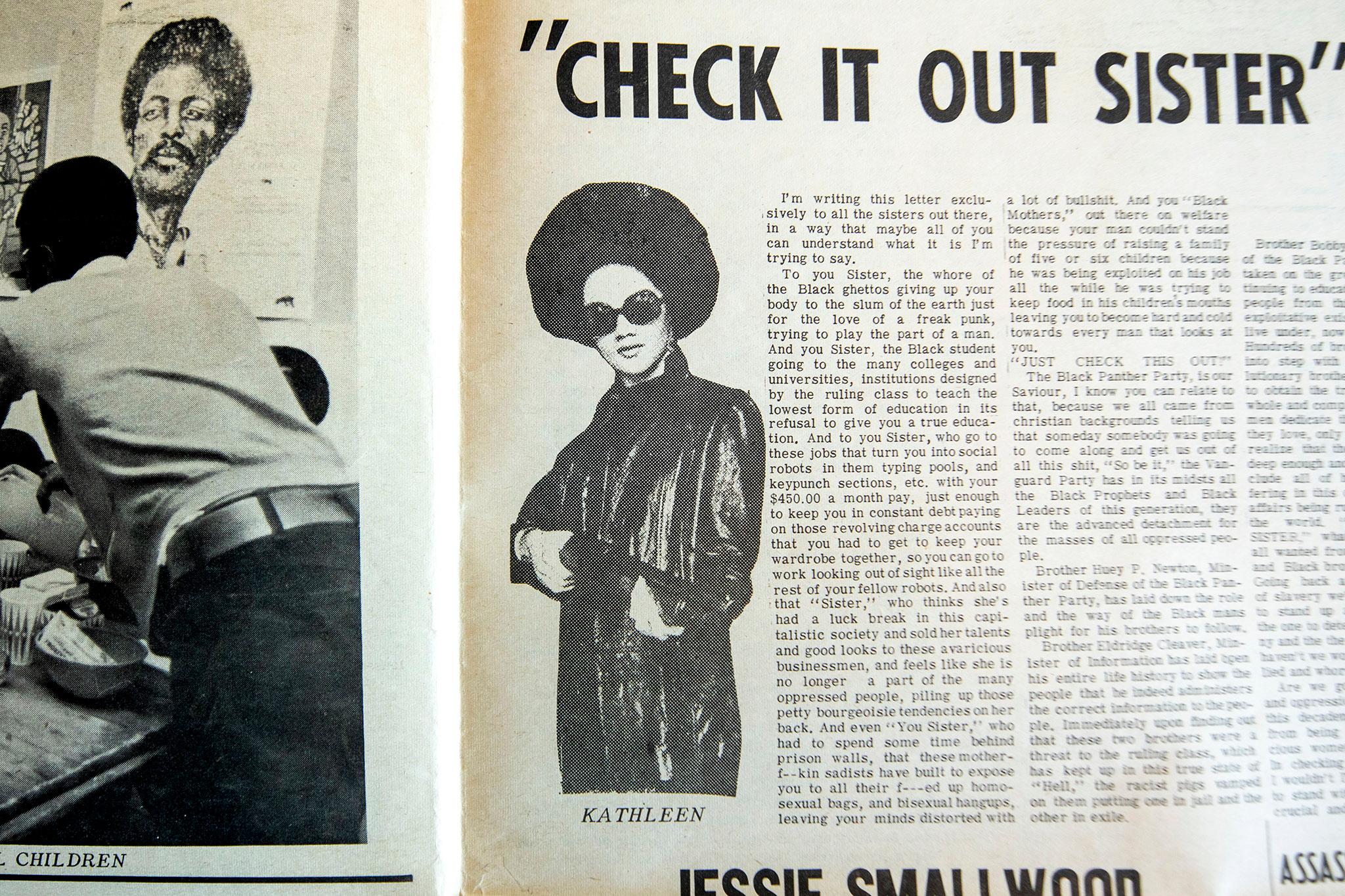

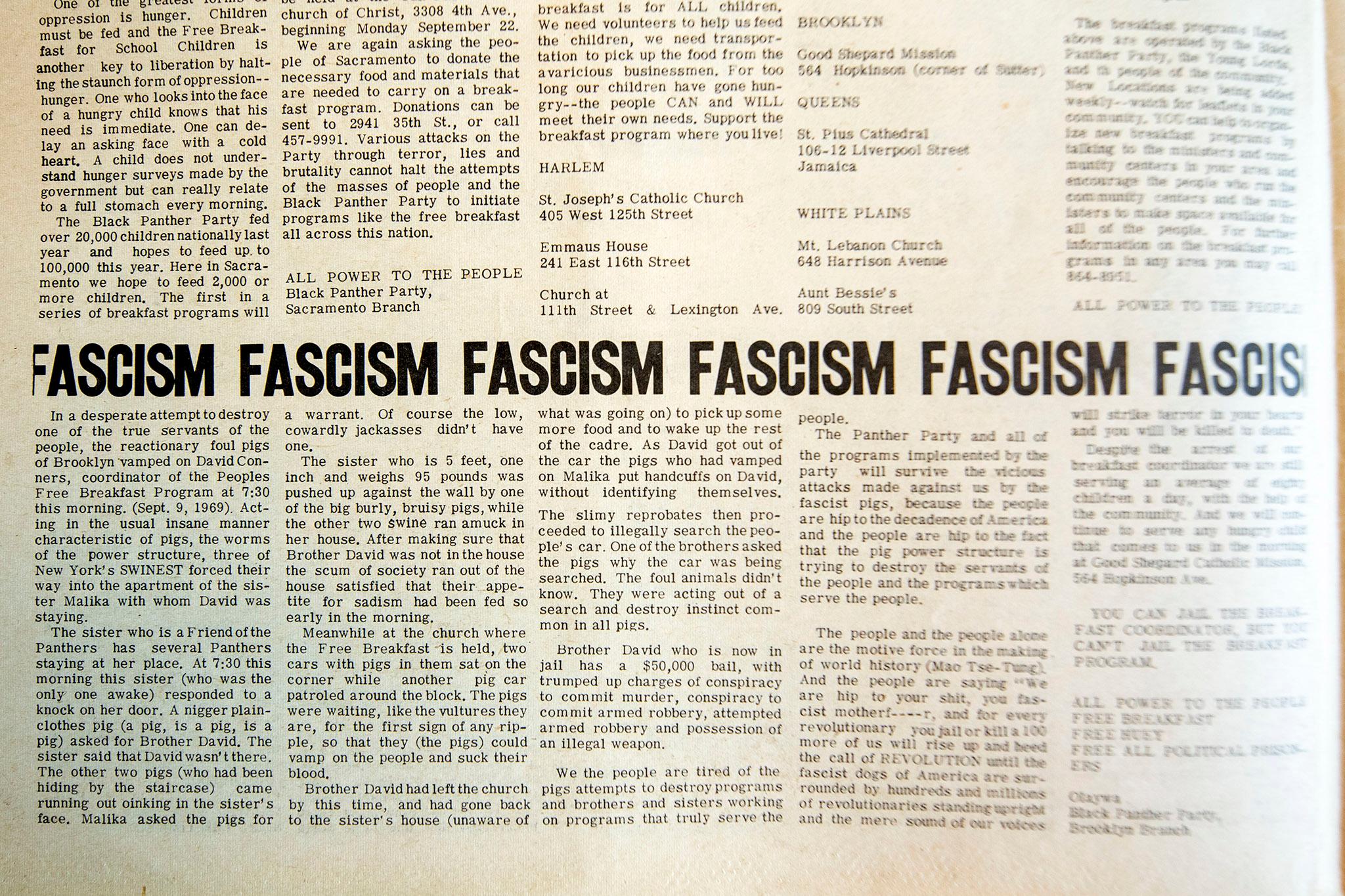

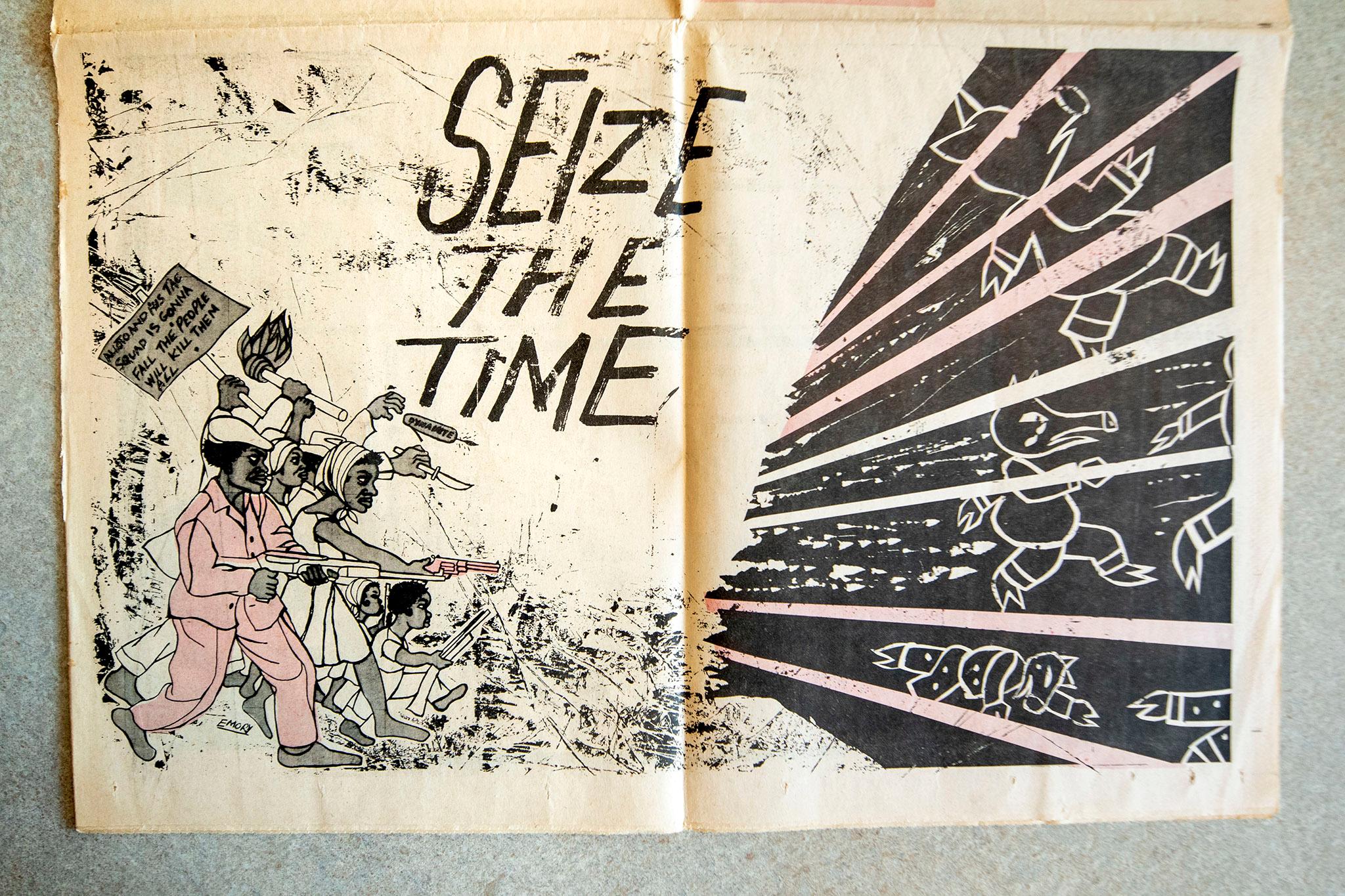

The papers are filled with discussions about what the group stood for, plus international news relevant to their cause.

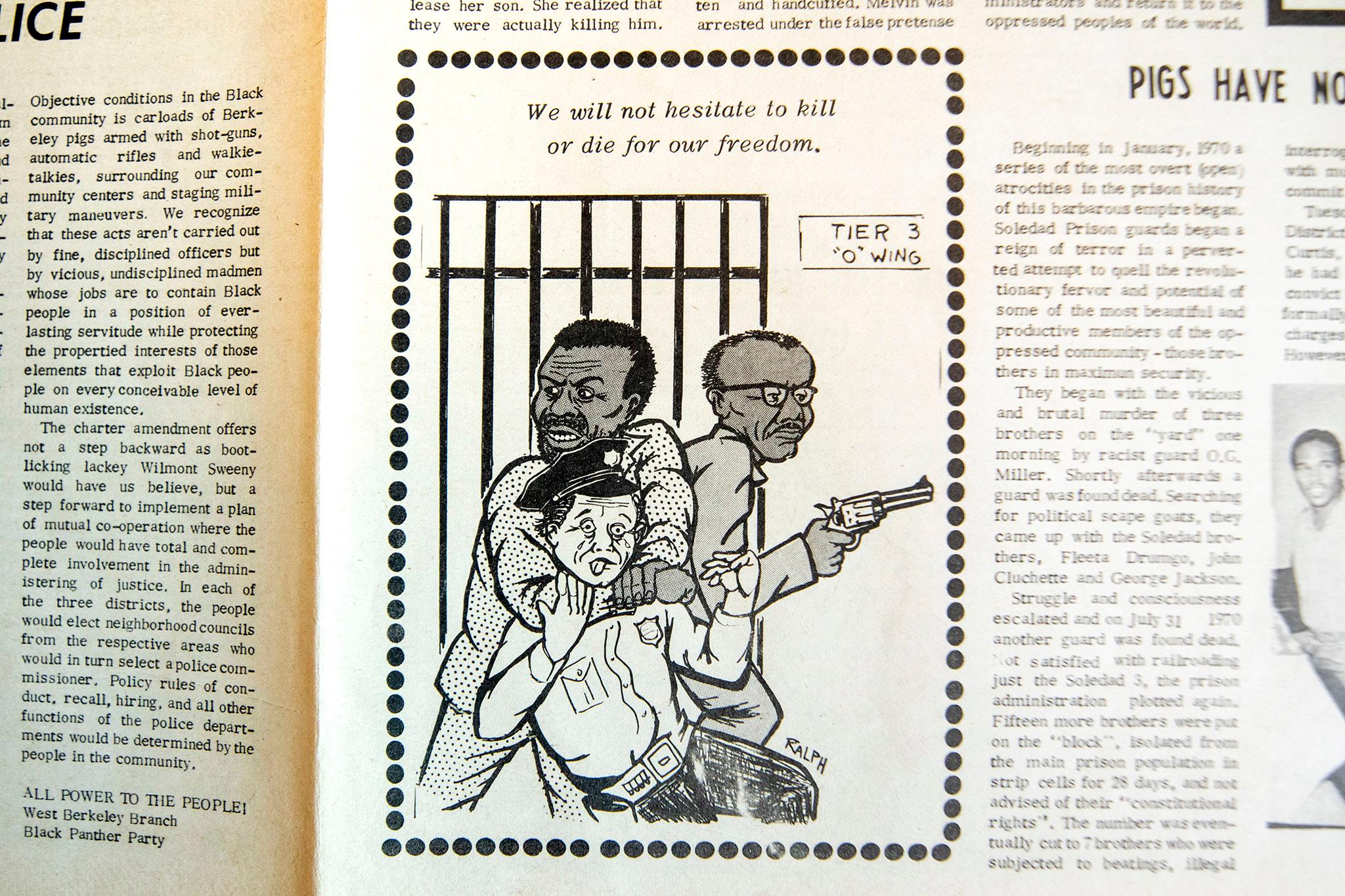

"Panther arrested for jay-walking," reads one headline about a man in Los Angeles. Next to it, an article about surveillance cameras in New York is titled "Mt. Vernon pigs to install people watchers." Other stories report the group's work feeding breakfast to children in cities across the country, the "torture" of a 19-year-old student nurse by New York City police and an effort by Black employees of Polaroid to stop sales of film to apartheid-era South Africa.

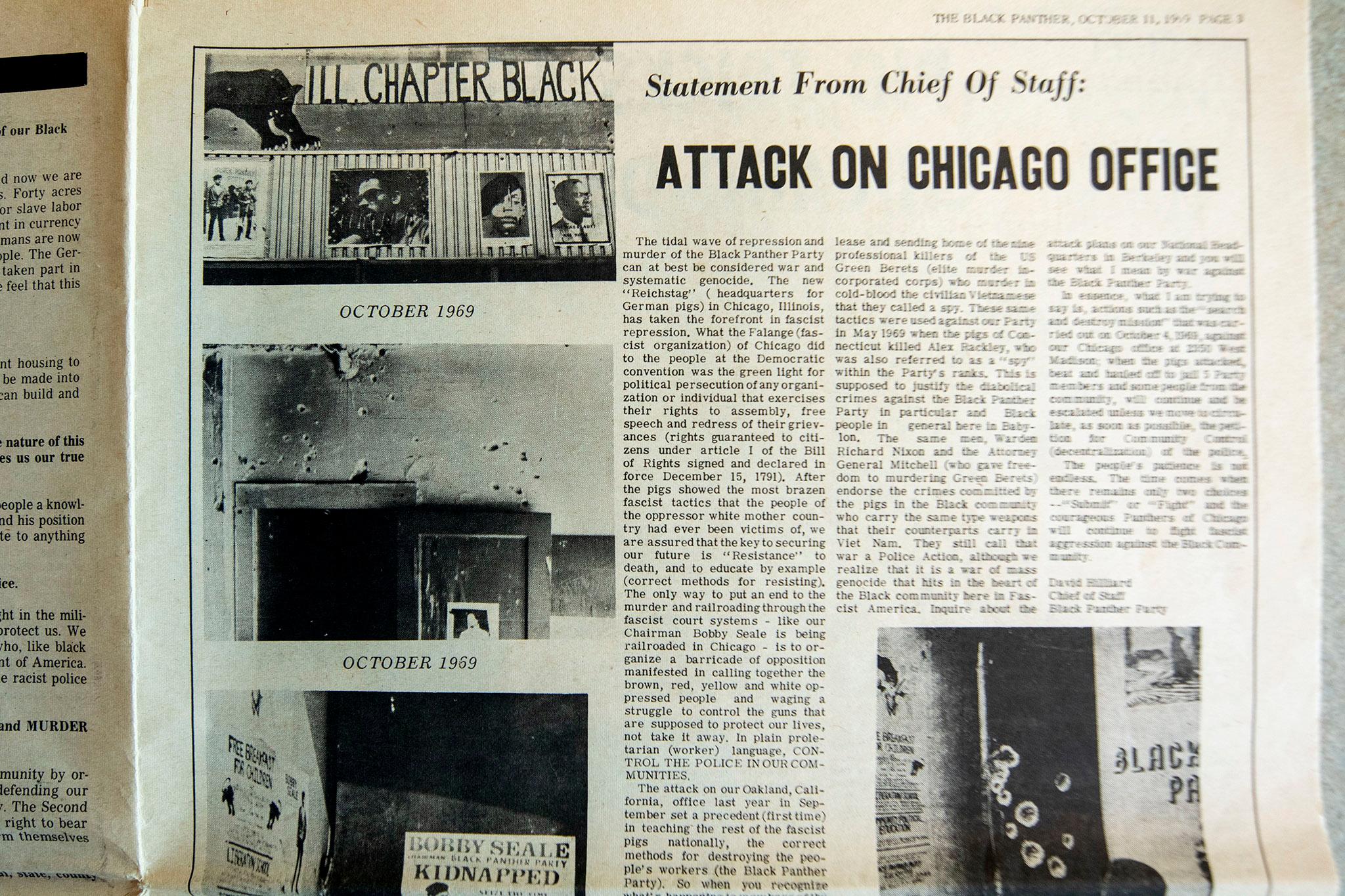

While there are few mentions of Denver in these eight papers, stories echo things that happened here. A statement about a 1969 police "attack" on party headquarters in Chicago came one year after officers raided Black Panther offices in Denver, shortly after local chapter founder Lauren Watson held his wedding reception there.

Many of the ideas printed in the '60s and '70s mirror the calls of for justice made by protesters on U.S. streets during the past year.

"We want an immediate end to police brutality and murder of Black people in the Black community," read one article titled "Community control of police," which argued for the change of Berkeley, CA's city charter to remove police from its streets. (Last February, Berkeley City Council approved a measure barring its officers from making traffic stops.)

Another story argues for the liberation of Palestine.

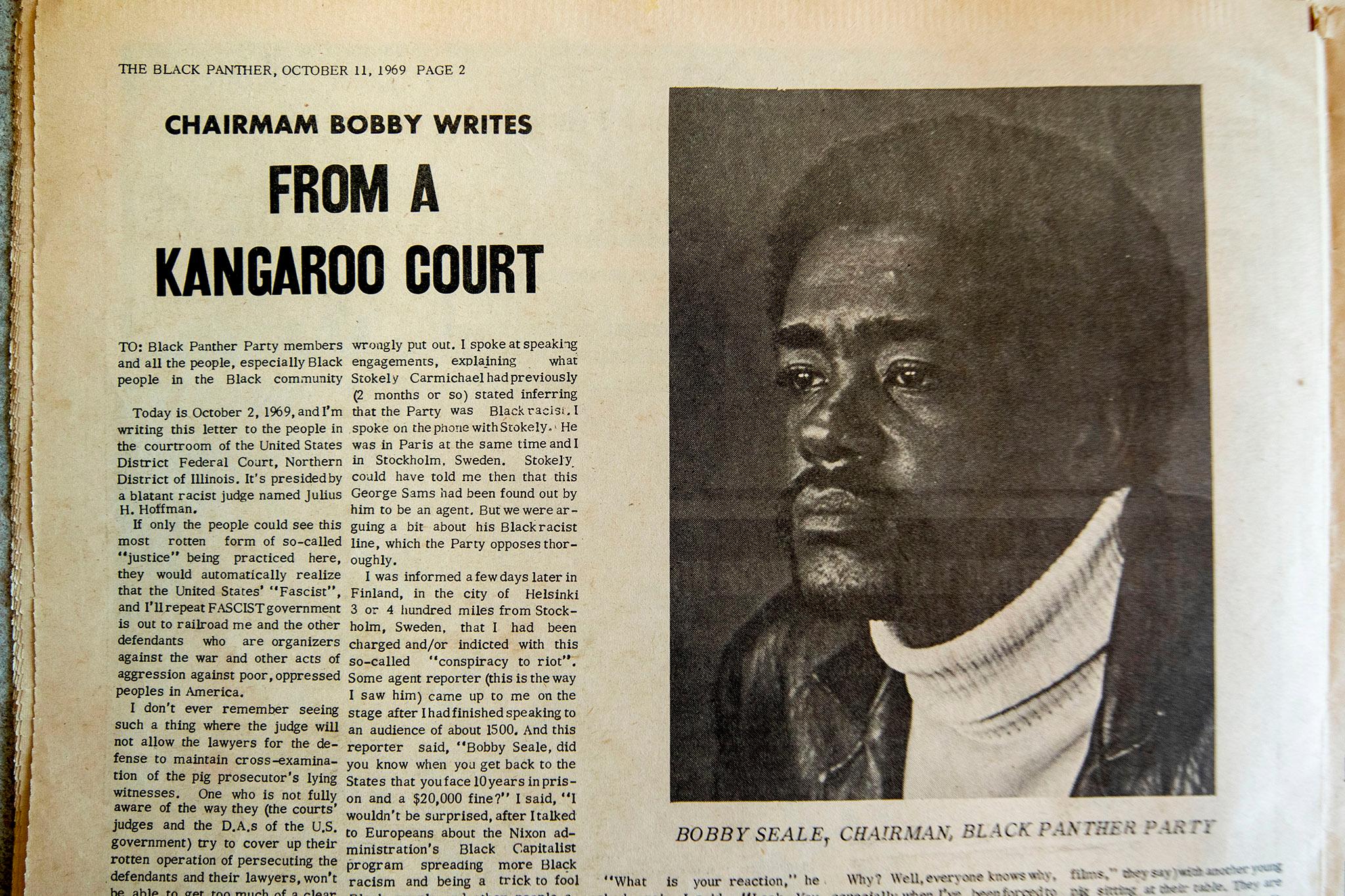

The papers also get into ideological weeds, and sometimes demonstrate how party members' ideologies changed over time.

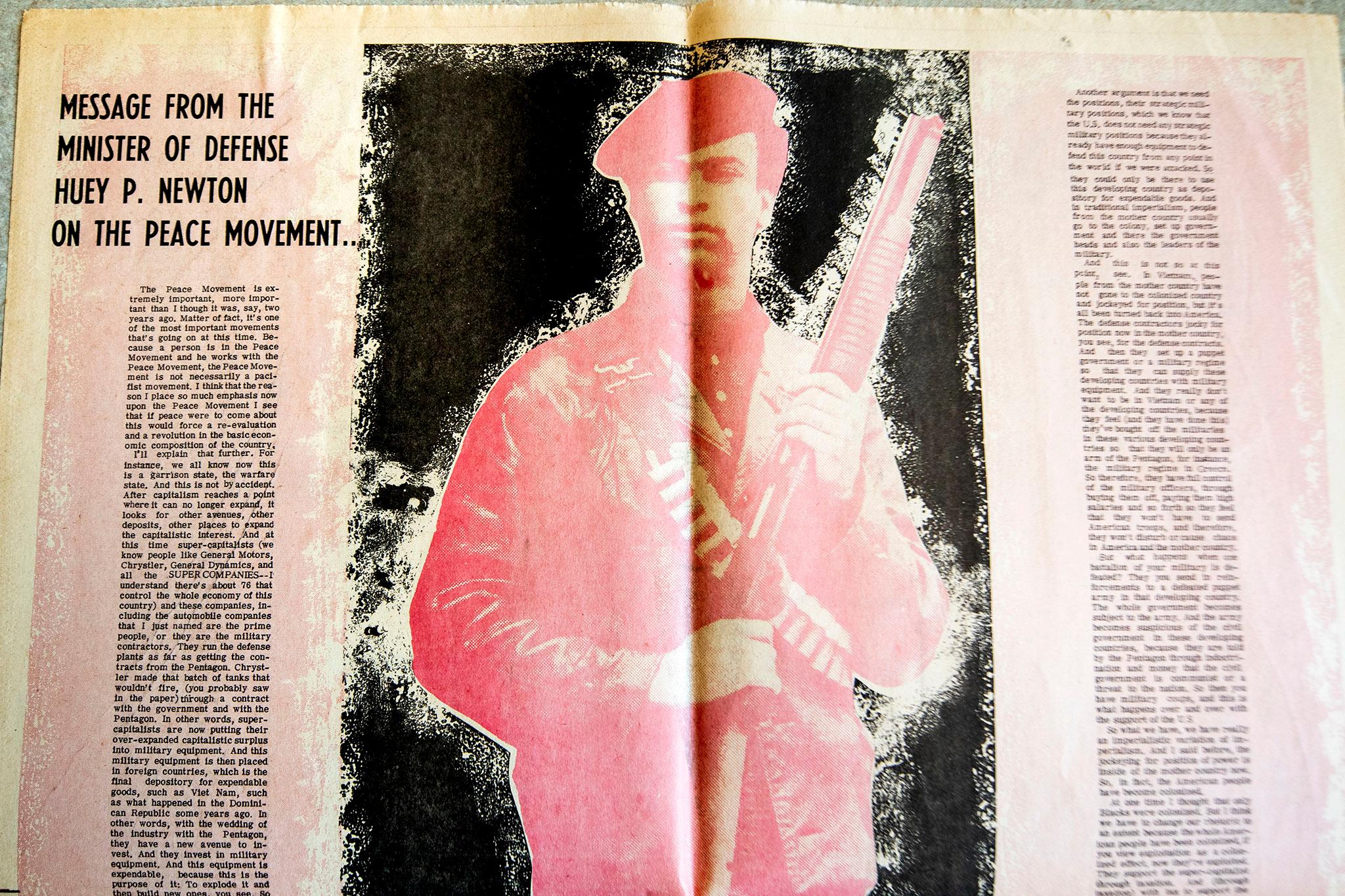

In one column, party co-founder and "minister of defense" Huey P. Newton wrote about his changing attitudes toward America's broader anti-war movement, which grew as he thought more deeply about capitalism's role in oppressing people both at home and abroad.

"At one time I thought that only Blacks were colonized. But I think we have to change our rhetoric to an extent because the whole American people have been colonized," he wrote. "We will still defend ourselves against attack and against aggression. But overall, we're advocating to end all wars. But, yet, we support the self-defense of the Vietnamese people and all the people who are struggling."

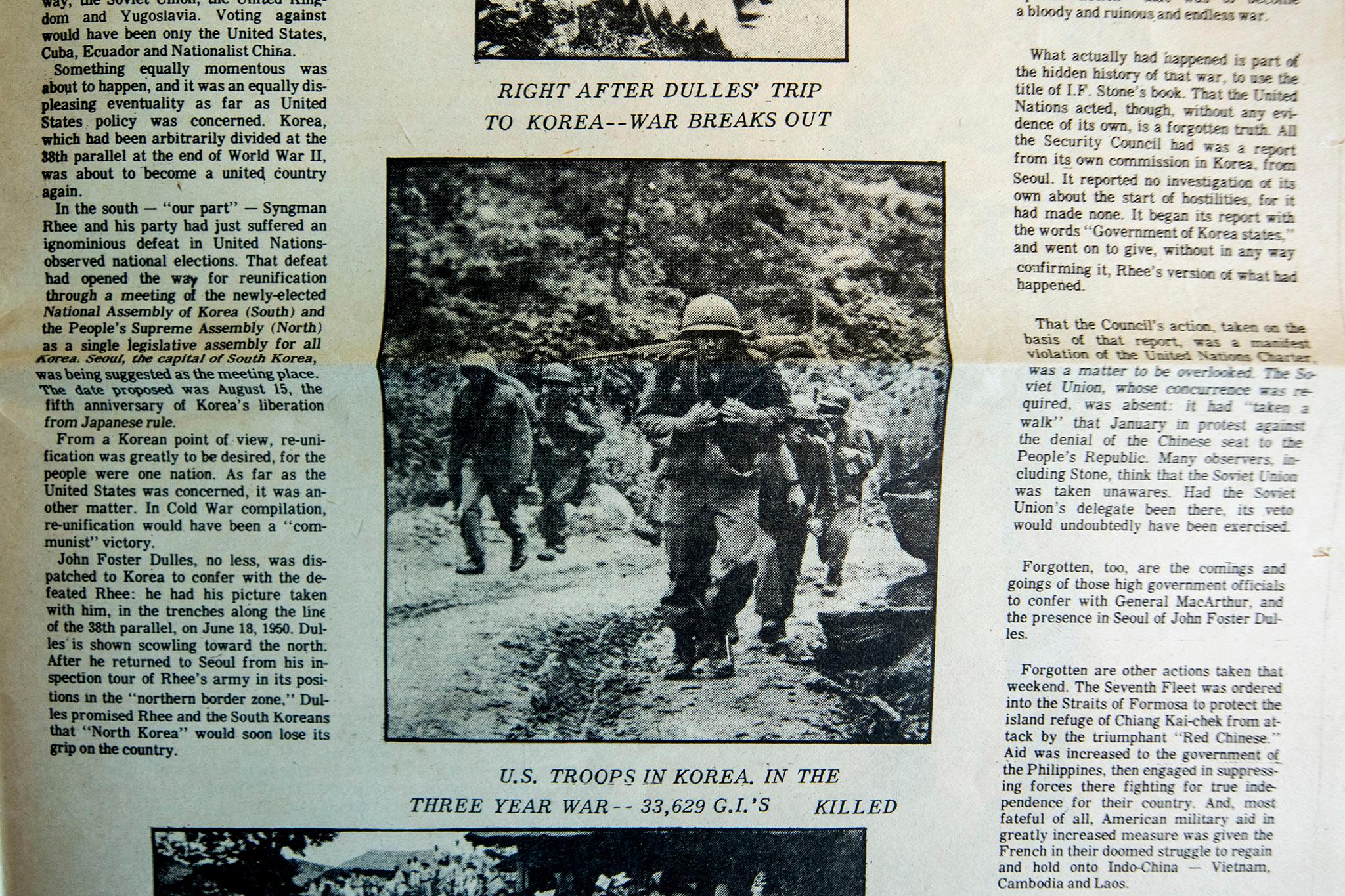

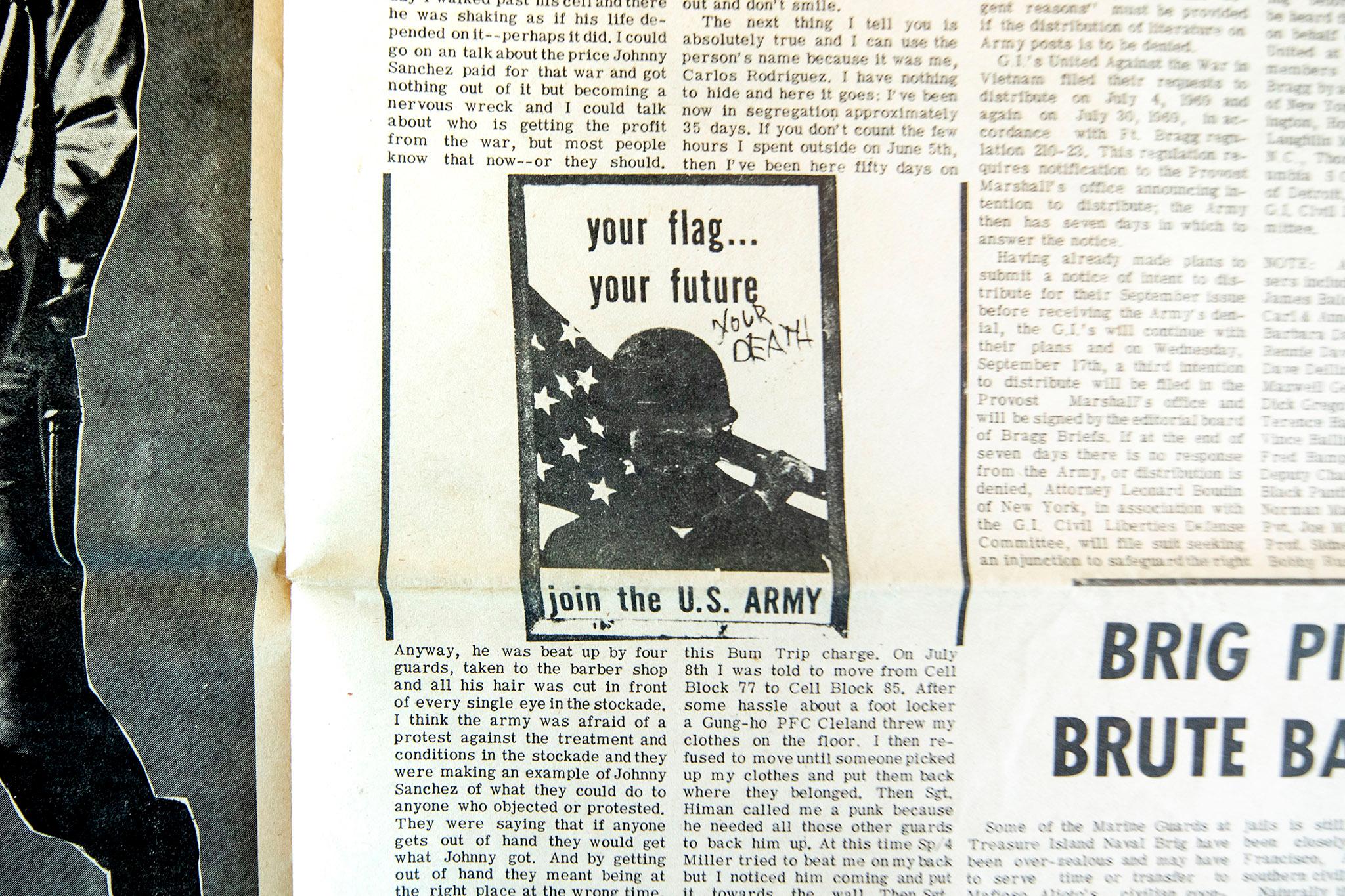

Editors dedicated a sizable portion of these papers to the Vietnam War. Columnists wrote about the connection between oppressed African American people in this country to Viet Cong soldiers, who they considered were defending themselves against what they believed was an imperialist U.S. agenda. They also included letters to and from members of the military, saying the government was "committing physical genocide" and "mental genocide" as they sent Black soldiers to fight foreign wars.

"Few of us escape," one veteran wrote. "I have and now I am mad as hell, because I saw myself 10 years ago as part of the great American plan. But Brother don't be fooled as I was. You cannot do anything for your people while in the clutches of the pig."

One issue features a letter from a Marine, still in active duty, who wrote that the government was training him to "kill my brothers, the Viet Cong."

His address ends: "Don't worry, I won't kill my people. Whitey doesn't know it, but he is training me to kill him when the situation arises."

Appended to the letter is a note from the editor: "We understand that the Marine Corp is the strongest bastion of racism and ignorance in the U.S. military complex. If the brother who authored this letter is racist, He is probably justified ... We hope that with growing consciousness he comes to understand all 'whiteys' are not on the same side and that all 'brothers' are not on the same side. ALL POWER TO THE PEOPLE."

Correction: Jameka Lewis' name was originally misspelled in this story.