Robert Rodriguez wasn't exactly thrilled when his father asked him to chauffeur a man around Denver.

Rodriguez, now a state senator, was 18 at the time. It was 1986. He had other things on his mind that did not involve chauffeuring a stranger. But he went ahead and did it.

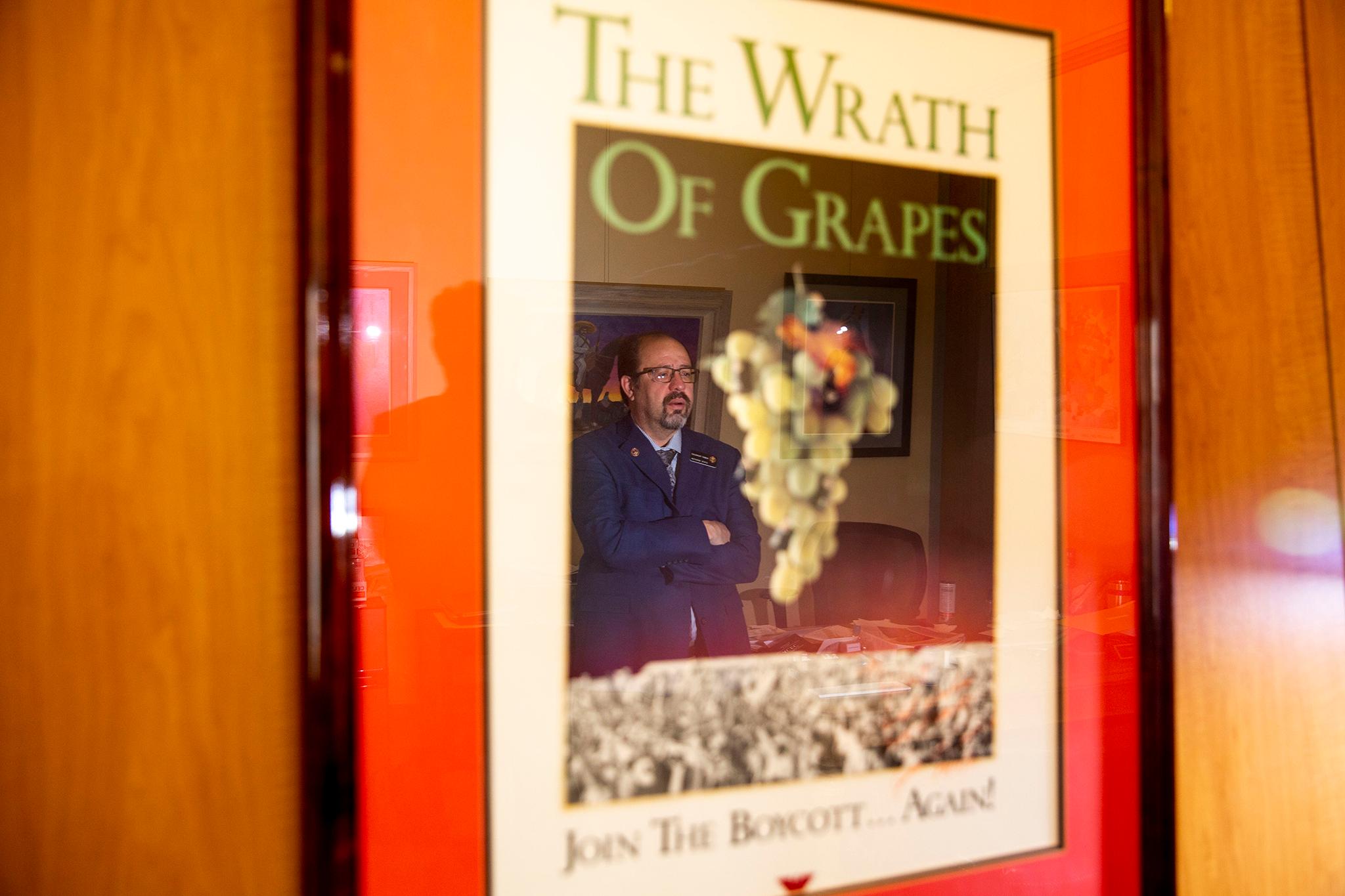

The man was short. He was quiet. After driving him around to a few events, he gave Rodriguez a poster opposing the use of pesticides for produce like grapes. The man even signed it, and the framed poster now hangs in Rodriguez's office. The red ink used for the signature is growing faint.

"My father was like, 'This is big,'" Rodriguez said. "And I was like, 'Eh, I want to go meet my friends.'"

That man was César Chávez, the iconic labor activist who in 1962, along with Dolores Huerta, created the National Farm Workers Association and would go on to advocate for workers' rights in California and beyond for decades.

Despite growing up in a politically active family, Rodriguez was in his thirties when he realized who he had met when he was a teenager.

Rodriguez, who represents Denver, now sees himself as an advocate for labor rights in the state legislature, someone who wants to stand up for the little guy the way Chávez once did.

"He was really nice," Rodriguez said inside his legislative office. "I was 18. I was a kid. Later, now, it's kind of a cool story for me to say I did meet him."

On Monday, the city will observe César Chávez Day, meaning city offices will be closed, libraries won't be open, and the Denver City Council will meet Tuesday.

It's a holiday the city has been observing for several years, well before then-President Barack Obama declared it a national commemorative holiday in 2014.

Former Denver Mayor Federico Peña said he found Chávez to be a calm and thoughtful person. When he met with Peña and other Latino lawmakers, they all pledged to support his boycott against Chiquita bananas, Peña said.

"There was almost a religiosity about him," Peña said. "It was an extraordinary experience meeting him."

Virginia Castro, a local activist in the Chicano Movement, met Chávez at least twice when he visited Denver. She recalls taking part in grape boycotts, prompted by his activism, as a student in the late 1960s and early 1970s by walking into a Safeway and squishing grapes.

She said Chávez was the type of person who didn't need to raise his voice to be heard.

"You heard him clearly," Castro said.

It's unclear how many times Chávez visited the city.

According to the city's landmark report on the city's Chicano and Mexican-American history, Chávez stayed at the Crusade for Justice headquarters on Cherokee Street and had dinner at Annunciation Church during a visit to Denver in 1967. The crusade was founded by Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales, who also worked with Chávez.

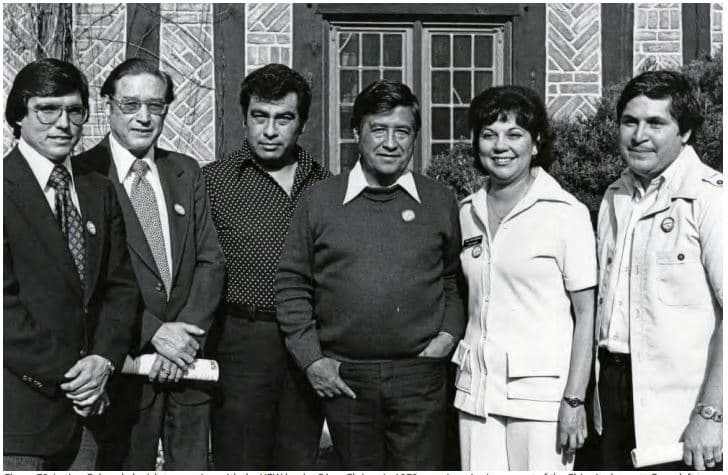

That visit is when Polly Baca first met Chávez, whom she considered a good friend.

Baca worked closely with Chávez on labor rights advocacy and registering Latinos to vote, including working alongside him in California for Robert Kennedy's presidential campaign. Baca would go on to have her own sterling career, serving as a state lawmaker and co-chair at two National Democratic Conventions.

"He was very humble," Baca said. "But when he gave a speech, wow. You got up on your feet. He was incredibly charismatic."

Castro, the wife of the late Chicano leader and state legislator Ricardo Castro, said she organized some of Chavez's visits for fundraisers with her husband's help. She recalled how big of a deal it was when he came to an event on the Northside along with El Teatro Campesino, a Chicano theater company connected to the United Farm Workers union that performed skits dramatizing the farm worker's plight.

"To this day, I just admire him so much," Castro said. "He was just a real special individual, and I think we were very fortunate and blessed to have been in his presence for a while."