Vitali Radchenko had an unusual summer vacation in 2022. As his classmates headed to camps and pools, he and his family boarded a series of planes to Poland, then headed east into Ukraine.

The Radchenkos were living just north of Denver when Russia invaded their country a year ago on Friday. Vitali's dad, Ihor, was once affiliated with the Ukrainian military and felt his family must go home to help with the war effort however they could. Vitali was too young to formally volunteer; instead, he spent time comforting kids his age, some who'd been through hell.

"There's a lot of kids that lost their parents and stuff," he said. Meeting them changed how he saw his new home in the U.S.: "You can understand that we've got a good life over here. There's no wars."

When they returned, Ihor approached the Ukraine Aid Fund, a Colorado nonprofit that's been sending medical supplies and equipment throughout the war, with an idea: Could they help fund flights and logistics to give some of those kids a break?

The Fund came through and raised about $25,000 to bring 14 kids to Colorado for two weeks. Most lost a parent as Ukraine fought back against the invasion.

Each stayed with a host family, creating a bond that organizers hope could turn into longer-term moves to the U.S.

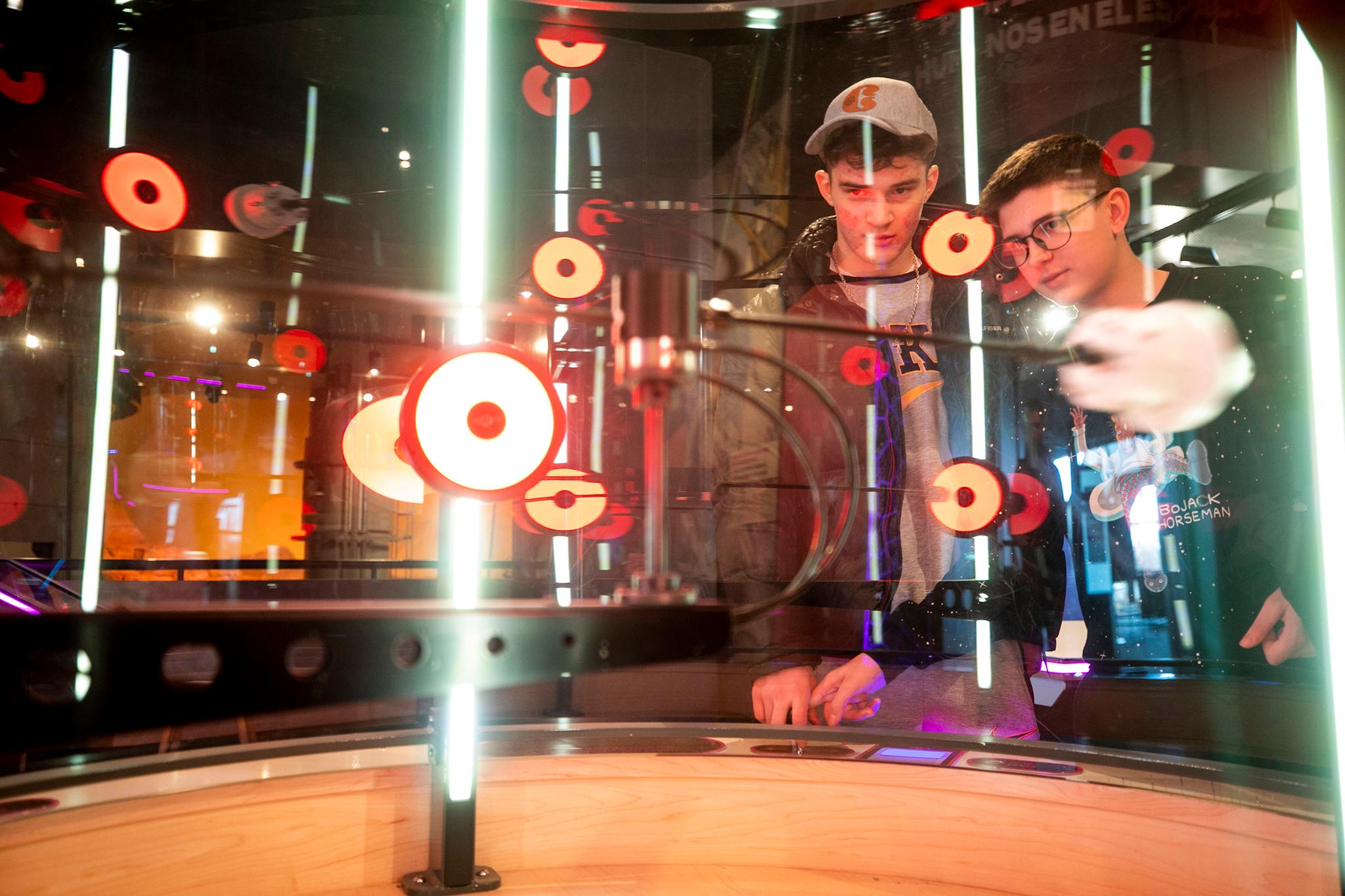

On a recent Monday, Vitali joined his new friends to a Denver Museum of Nature and Science free day. They were quieter than the other children buzzing around the exhibit.

Vitali's older brother, Vlad, who was living in Kyiv when the war began and spent much of the last year in Ukraine helping civilians get to safety, pulled up some images on his phone as the kids headed into the space exhibit and towards Mars.

"We saw a lot of Russian tanks, hopefully destroyed by Ukrainians. And we saw these poor people who were in shelters," he said, thumbing through images of the war's impact. "You can see, it's a civilian building that was destroyed. It was really hard to see that, you know, because we could feel how they felt."

The trip to Colorado was meant to remove kids from scenes like these, but the Radchenkos and volunteers with the Ukraine Aid Fund had more on their minds.

"We are giving them an opportunity to understand that this is a reset, this is their vacation," Dasha Panasiuk, a volunteer guiding group, told us as they huddled around a virtual reality ride, "but this could be their life, if they want."

In April, 2022, President Biden's administration announced Uniting for Ukraine, a visa program that allows Ukrainians to come to the U.S. for a minimum of two years, provided they have an American to sponsor them. Panasiuk said some, if not all, of the host families who housed kids during this visit have offered to sponsor them and their families.

"We're not closing the door on them after these 14 days," she told us. "We are going to continue to support them and give them everything they need to have a thriving and prosperous life."

Violeta Chapin, an immigration lawyer and clinical professor with the University of Colorado, said the program represents what the U.S. immigration system could look like.

"It shows that we can have an asylum, refugee process that is dignified and orderly and humane," she said. "The problem that I've seen, as an immigrant advocate, is that we have many other people from other countries seeking asylum in the United States that were not allowed to enter through a program like Uniting for Ukraine."

Biden's Uniting for Ukraine program does not offer permanent immigration status in the U.S., but recipients can renew their visas every two years as long as the program remains intact. It's similar to a program his administration announced in January to prevent people from Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela and Haiti from crossing the U.S. border without authorization. Instead, they're encouraged to apply for two-year visas from inside their home countries, if they have an American to sponsor their stay. In both cases, the temporary status is meant to give people a safe place to land, to work and to try to attain permanent asylum.

These two pathways, Chapin added, are uncertain like Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals and Temporary Protected Status, in that a sitting president could try to cancel them at any time. If they're not renewed, people living here under their protections could easily become undocumented. And while she expects the federal government will be open to giving Ukrainians safe passage as long as they need it, she said people coming here from other nations may not receive the same welcome.

"At least from my perspective, it also helps that they're white," she said. "I certainly want to help people from Ukraine, but it saddens me that we have not set up similar processes for people from other countries."

If any of the kids who visited this month do plan a long-term return, they won't be alone. Federal data shows more Ukrainians received permanent immigration status here in 2022 than any year in the last two decades - Biden's United for Ukraine program doesn't impact those numbers, since it doesn't offer a pathway to permanent status.

For local Ukrainians, Biden's visa program is nice, but it's just a temporary fix.

By the end of their two weeks in Denver, the visiting kids had grown back into themselves. They were loud, boisterous and giggly when they sat down for sushi before heading to the airport and back home.

"When they first came here, they couldn't even smile," Taras, another Radchenko son, beamed as he scarfed teriyaki chicken. "Look at them right now, they're all smiling and stuff."

Vlad, who's 15, said he loved seeing the Nuggets play during his visit.

"He loves basketball, and he really dreamed to go to basketball game," Vitali said, translating for him. "Dreams do come true!"

Valeria, who's 13, said she's sad to leave but ready to return to her family. She would like to come back, either for a visit or, maybe, to go to school.

Bob Kagan, who was born in Ukraine but now lives in Parker, said he's hoping the kids he hosted will find their way back to him.

"It's gonna be really tough parting with them. Some of them are already saying, 'Were going to be coming here visiting you, staying with you.' And, obviously, we said the door's open any time you're ready to come here," he said. "If you-know-what hits the fan, we'll obviously do anything to pull them out."

But Taras Overchuk, president of the Ukraine Aid Fund, said his people need more.

"In order for these kids to stop suffering, this war needs to be complete. And the only way to make it sustainable is Ukraine wins this war," he said. "Until then, it's really hard to say you are satisfied."

He's glad kids like Vlad and Valeria have an option to leave the war behind. But a year into the invasion, he said they won't truly be safe until Russian missiles no longer breach Ukrainian airspace, and the country's borders are secure once again.

"Nobody needs to lose their fathers anymore," Overchuk said.