During Mayor Michael Hancock's three terms in office, he and the business community created a gateway to Denver -- an entrance for those with money and an exit for those without enough.

It's a dynamic that Hancock himself says he's been aware of for about a decade.

In 2013, Paul Washington, the executive director of the Office of Economic Development, came to Hancock, he recalled. "Mayor, we have kind of an amazing dynamic happening in Denver. One is we're growing exponentially. And two, we have a run on affordable housing. And it's going to cause a problem if we don't find a way to get up on it."

By marketing the growing city -- the joint legacy of mayors Federico Peña, Wellington Webb and John Hickenlooper -- Hancock brought 17 international nonstop flights to Denver International Airport. He attracted massive corporations to do business in town, selling the city's affordability, low-taxes and business-friendly environment.

He oversaw the planning department as developers built pricey new housing for singles and couples on top of historic neighborhoods where working-class families once thrived.

And some who lost their homes and lived on the streets were banned from setting up tents for shelter. When they did, the city swept them from block to block.

Meow Wolf, the Mission Ballroom and Levitt Pavilion rose, as Anschutz Entertainment Group and Live Nation raked in profits selling expensive tickets to concerts held in city-owned parks. Meanwhile, safety officials booted homegrown artists from their industrial live-work warehouses over permitting issues and many fled to cheaper cities.

City-funded, colorful murals of Black and Latino residents were painted on the walls of neighborhoods as communities of color struggled to hang on and the percentage of white residents rose.

Still, the city ranked as one of the best places to live, start a business and raise a family in the country, and more people came.

Early in his tenure, Hancock got a reality check about the side effects of the city's growth while he was walking on the 16th Street Mall.

A man told him, "Mayor, what about those of us who are being left behind right now? Those of us who are unable to get the jobs that are coming with this new economy in Denver. Those of us who can't afford to live here anymore."

"It was that moment where I was like, you know what, we've got to always make sure that we bring people along," Hancock said.

He recently told Denverite his legacy will be determined by the answer to this question: "How did you respond to unprecedented growth?"

So, how did he respond?

The official answer is told in a 95-minute legacy video titled "Denver Rising: The Transformational Leadership of Mayor Michael B. Hancock," a glowing official account of Hancock's 12 years, produced on the taxpayer's dime by the city's well-staffed public relations team.

The copyright owner? Hancock himself. It's unclear how much the film cost, but Hancock spokesperson Mike Strott told Denverite that "We produced in-house - so just our blood, sweat, tears, personal time and the like."

The "Denver Rising" Hancock story goes like this...

A bright, friendly kid with political ambitions came from poverty and wanted to be the city's first Black mayor -- until Webb beat him to it.

Hancock rose to be a community leader, head of the Urban League of Metropolitan Denver. He was a mentor to younger community activists, a stalwart in Eastside organizing and a racial equity champion.

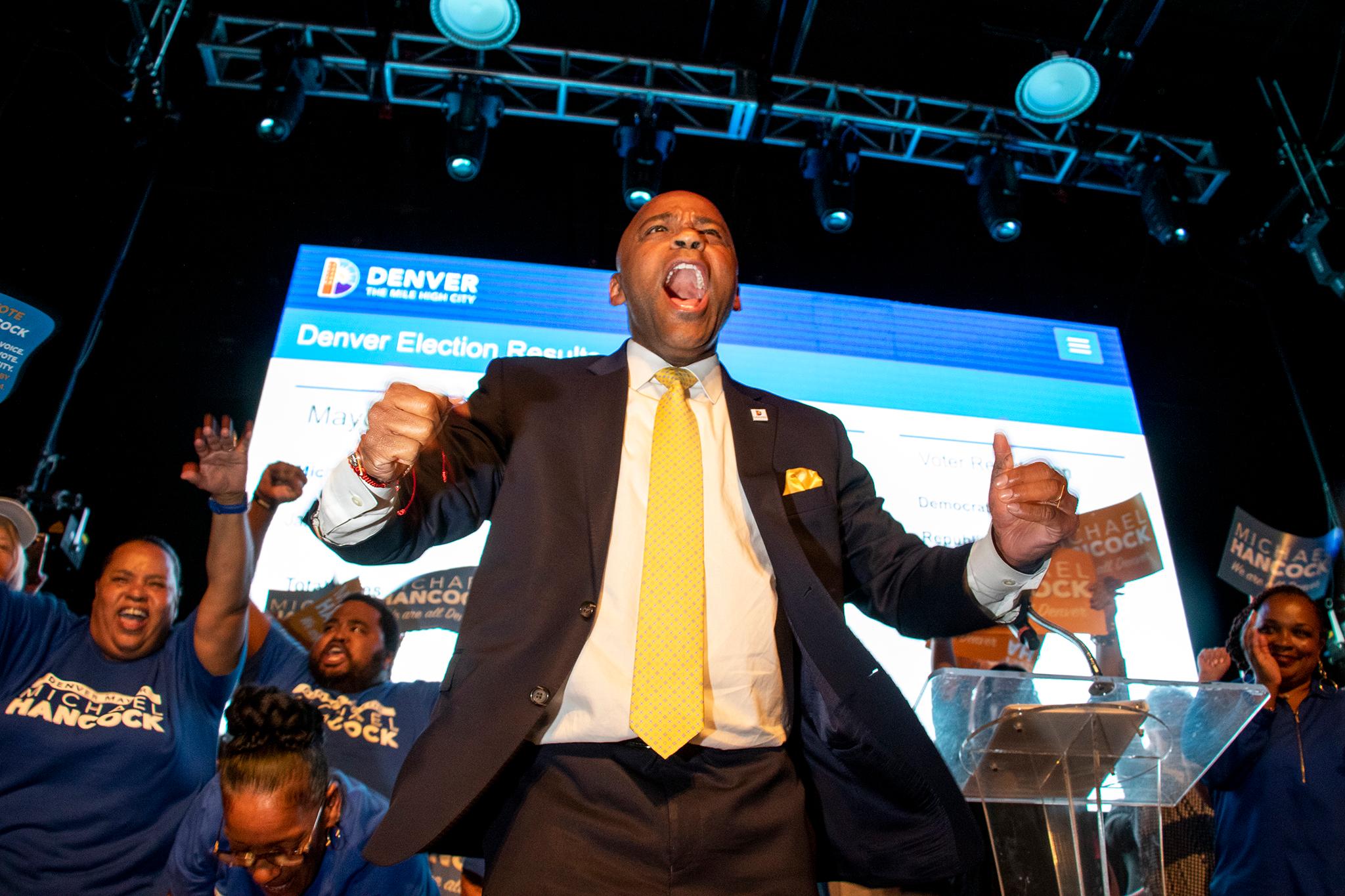

In 2004, he became a City Councilman and then, in 2011, mayor, who pulled the city out of the Great Recession and a financial crisis by cutting city expenses and asking for taxpayer help, a request that could have put off voters. Attracting new businesses and international flights to town, he boosted the economy.

While he opposed the legalization of cannabis, when the voters spoke, he adjusted and Denver became the first in the country to create a regulated industry.

He confronted the housing crisis, struggled to manage homelessness, led Downtown out of devastation wrought by the pandemic and civil unrest during his third term, and launched an ambitious recovery setting up the city for future success.

But there's more to Hancock's story than what's just in the film.

His 12 years in office were sandwiched between crises: mass foreclosures in the beginning and economic fallout from the pandemic at the end.

He was inaugurated during the wake of the Great Recession after thousands of families were displaced through bank foreclosures.

Their properties were listed for cheap. The cost of housing, when Hancock took charge, was "crazy low," Oakwood Homes developer and Hancock backer Patrick Hamill told Denverite.

Those foreclosed homes were attainable, at least for those who had enough money for a down payment and hadn't lost their housing, said Heather Lafferty, the outgoing CEO of Habitat for Humanity of Metro Denver.

For many who had suffered bankruptcies, lost equity or found themselves shouldered with debt, even those homes were out of reach. A wave of longtime Denverites were moving to other cities and states around the time Hancock became mayor -- a bleeding that continued, even as the population grew with an influx of transplants.

The arrival of so many newcomers wasn't an accident, though. It was a product of massive marketing efforts.

For companies looking to relocate to a place with a low cost of living, low taxes and low housing prices near nature and with some cultural amenities, Denver had appeal. High-skilled, well-paid workers employed by businesses that Hancock's Office of Economic Development and the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce recruited poured in.

Denver's airport became the world's third busiest. Hancock kept the National Western Stock Show, which planned to leave Denver for Aurora, in the city. The National Western Complex rose in Elyria-Swansea -- even as voters turned down a bond to pay for a new arena.

He envisioned "a gateway to the city" and "a Corridor of Opportunity." He backed developers and artists who created the River North Art District with retail and housing marketed for newcomers. Meanwhile, longtime Black and brown residents of Five Points, Globeville and Elyria-Swansea left.

"It has really just been a corridor of destruction and disaster and destabilization," said outgoing Councilmember Candi CdeBaca, who was mentored by Hancock when he led the Urban League. She said he lost her friendship over the rebuild of Interstate 70 through Globeville and Elyria-Swansea.

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Much of Hancock's final term, strongly affected by a pandemic fully out of his control, was bleak.

Businesses were forced to close. The cultural economy suffered and venues shuttered their doors. Workers stopped coming downtown and many may never return.

Residents lost their homes and some began living on the streets. Fentanyl hit the city's drug supply, and some users, who had managed to hold down jobs, were crushed by the potency of the new, industrial drug; Treatment and recovery proved harder than ever.

City departments' efficiency declined, as workers across agencies were redeployed to address the city's rising homeless crisis.

Water fountains dried up. Public restrooms were locked. The transit system became a shelter. Union Station, for a while, became a de facto safe drug-use site, where people who overdosed could have fast access to opioid reversal drugs.

COVID-19 made many sick. More than 1,570 in the city died.

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Missing from "Denver Rising" are a few notable moments, including one that could have ended Hancock's tenure as mayor.

During Hancock's second term, Leslie Branch-Wise, a police detective who served as his security detail, came forward with claims of sexual harassment and texts from 2012 to prove it. As a result of their boss's behavior, all city workers underwent training about appropriate workplace conduct, recalled criminal justice advocate Lisa Calderón, who was working for the city at the time and said the move gutted Hancock's reputation with city employees.

There was also that time in 2020 when he told the people of his city not to travel over Thanksgiving to avoid spreading COVID -- to sacrifice time with family in the public interest. And then he got busted in the airport flying out to visit his daughter. At the time, Channel 9's Kyle Clark indicated the mayor had lost all credibility, tweeting: "This is the last time Denver needs to hear public health guidance from Mayor Hancock. If the city has a leader who actually follows the advice they give the public, we'll put them on instead."

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Hancock regrets those things, he told Denverite a few months back, bringing up both incidents without prompt. He says he let the people down -- even if he did not step down from office while many called for him to do so.

The video doesn't address Hancock's Urban Camping Ban, which was passed in 2011, largely to stop Occupy Denver's anticapitalist protesters from squatting in Civic Center Park, according to outgoing Councilmember Robin Kniech. The policy effectively criminalized unsheltered homelessness.

Nor does "Denver Rising" look at how the administration's ongoing sweeps of encampments, which Hancock still says are necessary for public health and safety, were widely criticized by medical doctors and homeless service groups working on the frontlines of the homeless crisis. Those experts said the sweeps decrease life expectancy and make it harder to connect residents to long-term housing, healthcare and social services and ultimately lead to more unsheltered homelessness -- which has increased since he took office.

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

We hear nothing in the documentary of the high-profile law enforcement killings that took place under Hancock's watch: the shooting of Jessie Hernandez, gunned down by Denver Police in an alley, which led to a nearly $1 million settlement. Or Michael Marshall, who was killed by Sheriff's deputies in 2015 -- which led to a $4.65 million payout. Or how taxpayers subsidized such law-enforcement violence -- largely targeting Black and Latino residents.

The official story does little to acknowledge the Denver Police Department's violent attacks on people exercising their First Amendment rights during the summer of 2020. Or the time officers fired into a crowd, injuring six bystanders Downtown, as bars let out in the summer of 2022.

Instead, Hancock's people positioned him as a champion of racial justice and police reform, kneeling in solidarity with protesters after the murder of George Floyd at the hands of a Minneapolis Police officer.

"Denver Rising" doesn't acknowledge the recent spike in evictions. Or the pain of displacement from the perspective of longtime Black and Latino residents -- and teachers, city workers and others -- forced to leave the city, unable to afford home ownership or rent.

Also not heard in the video are the voices of real-estate bigwigs like EXDO Development CEO Andrew Feinstein and Hamill, who backed Hancock from the beginning and profited, for years, off of his commitment to rapid growth. Nor the lobbyists from CRL Associates, Sewald Hanfling Public Affairs or the Pachner Company, who often had his ear, according to an in-depth investigation from Colorado Public Radio, even as residents from his community complained they were ignored.

The documentary doesn't reflect the personal toll serving as mayor took: how he lost friends and even his marriage.

Through it all, even when he felt it "sucked," Hancock loved serving the city, according to his family.

His daughter, Janae Hancock, who was 13 when he was first elected mayor and is now a TV journalist in Kansas City, told Denverite that "when he went to work every day, he was like a kid preparing to go to the candy store. He truly enjoyed the past 12 years. He loved going to work every single day and even if there were ups and downs, he was proud to serve the city of Denver."

Even during the pandemic, he'd go to his upstairs home office, wearing a dress shirt and basketball shorts, and he'd hold meetings all day.

The mayor protected his kids from bad news, criticisms and threats he faced. He showed up to Janae's cheerleading events. He would come home and spend time with family -- even if he left to visit injured officers and firefighters into the night.

"If there's any type of legacy that he leaves behind, I hope the City of Denver sees that that is going to be perseverance," she said. "Through it all, he just -- he never gave up. There were a lot of sleepless nights, and there were nights when he just didn't want to eat because he had a lot on his mind."

But in the morning, he left the house "with a smile on his face," she said, eager to take on a new day.

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

The decisions Hancock made during those long days and nights have left the public grappling with whether he's to blame for the city's current ills.

"It would be one thing if Denver was the only city dealing with these issues," said Councilmember Paul Kashmann. "Every city -- every big city that's having any degree of success -- is fighting the same trio of issues: crime, homelessness, and it's too expensive.

"It's more endemic to the way our American Dream has unfolded in that it's unfolded brightly for some and not so brightly for others and not at all for others," he continued. "And we've got to figure out how to get a more equitable distribution of wealth."

Eric Boschmann, a professor in the Department of Geography and the Environment at the University of Denver and co-author of "Metropolitan Denver: Growth and Change in the Mile High City," hopes the challenges Denver faces won't be blamed on Hancock.

"Cost of living, affordability, homelessness, office and retail vacancy rates, declining public transportation ridership, rising crime/violence, air quality ... and many more -- these are urban challenges many cities are facing and are symptoms of much much broader trends," he wrote Denverite.

"Mayor Hancock navigated the city through some tough economic times," Boschmann added. "During his tenure the population continued to boom and the city and region remained economically vibrant. He really carried on the growth tradition of many recent Denver mayors."

Former Mayor Webb, Hancock's mentor, occasionally took umbrage with the administration -- particularly over his planning department's support of development on the Park Hill Golf Course, 155 acres of Northeast Park Hill protected by a Webb-era conservation easement. But overall Webb thinks Hancock was a good mayor.

"One thing about being mayor of any city is that you never can pick the issues that you have to deal with," said Webb.

A mayor only has so much power.

"I'm envisioning being in a kayak going down a raging river," said Kashmann, who also had strong differences with Hancock but described him as an honorable man who did his best to serve the city. "You got some control. But you can't totally tame the river. You're trying to point it in the best direction you can."

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

One new direction Hancock took, at the urging of advocates and city council, was trying to address housing and equity, unlike past mayors who mostly focused on overseeing police, libraries and parks.

"We started allocating money for affordable housing, not really understanding the size and scope of it," Hancock said.

The word "equity" started showing up in reports from city agencies. At-large Councilmember Kniech, who is also leaving office after 12 years, said she and others who had been longtime affordable housing advocates leaned into the mayor's values of economic and racial justice. Council and the mayor raised the minimum wage -- first at the airport, then citywide. Council pushed Hancock to find city funding to address the housing crisis through a mix of taxes and fees on developers -- a product of advocacy that continued throughout his three terms.

Over the years, he worked with Council and voters to create the city's Affordable Housing Fund, a Homelessness Resolution Fund, and the Expanding Housing Affordability program that put more of the burden of solving the affordable housing crisis on developers.

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

"He was willing to partner with the Council," Kniech said. "And was unafraid to leverage those partnerships. And he was unafraid to try new things, evolve the role of the city. And he was willing to even change his own positions to do those things, and that's an important sign of leadership."

While Hancock said he's tried to put policies into place to stave off gentrification, some of the results might not be seen for decades.

"I think we corrected quickly and began to turn," Hancock said. "But it's like turning a ship, you know? You've got to get people trained. You've got to get them to believe and trust that what you're trying to do is to be inclusive and to make sure everybody comes along."

Some say Denver should have grown faster and city government needed to get out of the way of development.

River North Art District developer Feinstein, who describes Hancock as a close friend, believes the outgoing mayor will go down as one of the best the city's ever had.

Despite the sluggish and bumpy work on the Great Hall at Denver International Airport and the Convention Center, those projects, along with the creation of the National Western Complex and the boom on Brighton Boulevard, will all be remembered as signature Hancock-era projects that future Denverites will praise him for creating.

While Feinstein has appreciated the mayor's commitment to growth, in the wake of the pandemic, the city's permitting office times have been lagging. Feinstein also wants private developers to operate with fewer restrictions and fees. Government, as he tells it, is interfering with the creation of housing.

"I don't think we grew fast enough for the amount of people that wanted to come here, for residents and as well as businesses," Feinstein said. "I think we could have grown even faster."

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Hamill, too, expressed concerns about current city operations.

"I think COVID has caused a lot of disruption in the efficiency of how the trains run on time."

Since the pandemic, city departments have had timing issues, he explained. "When you want to do business with the city, you want predictability when you can get things done. And that's been strained as a byproduct of, obviously, COVID."

While Hancock has largely championed development, a few of his big policies, like Expanding Housing Affordability that forces developers to do more to pay for income-restricted housing projects, were unpopular with developers like Feinstein, who said they'll ultimately lead to a higher cost of living.

The growth the real estate industry desired troubles some of Hancock's fiercest opponents.

"It's really a cancerous growth," said Denver historian Phil Goodstein, a longtime critic of the city's leaders and business establishment. He refers to Hancock as "a stalwart of the status quo."

"It is not a growth that has led to a flourishing community or even a sense of community or anything," Goodstein said. "It has emphasized Denver as a generic directionless city with no vision."

Hancock's administration delivered a "government of big business," one that would "unquestionably serve developers and those with power," the historian added. The mayor continued the tradition of public-private partnerships that go back at least as far as former Mayor Federico Peña's time and that have resulted in "a cult of Disneyland planning."

Outgoing councilmember CdeBaca said growth isn't the problem. She's critical of the type of growth Hancock championed because it pushed out communities of color.

Growth "doesn't have to be about displacement, and there was so much information out there even at the beginning of his term about how to do development without displacement," she said. "And it all went ignored."

In his time in office, Hancock led Denver as it became a "transient city," said community activist Jeff Fard, better known as Brother Jeff.

"It's hard to see a signature of Mayor Hancock on this city, other than massive development, large corporate interests," Fard said.

Newer residents view this as a place to build a profession but not a city to plant long-term roots, and the city has a "stack-'em, pack-'em mentality," Fard explained. Denver has been treated like an "investment place" and "to me, that's at the expense of the community feel."

LaMone Noles, a longtime community leader in Northeast Park Hill, sees the good and bad of Hancock's legacy.

"In the span of 12 years as Mayor, he had the privilege of presiding over the growth of Denver from just another Midwestern city to an internationally recognized metropolis," she said. But his vision of growth has served transplants and has been disconnected from legacy communities of color who have traditionally had a strong relationship with Denver government.

"Mayor Hancock will be remembered for not protecting those relationships when it was disrupted by gentrification and affordability issues with housing and the high cost of living," she said.

Dwayne Peterson, who has lived in Denver without a home for the past five years and is serving on one of Mayor Mike Johnston's transition committees, said that people suffering homelessness often have Hancock's name on the tip of their tongue.

After all, Hancock pushed for the Urban Camping Ban and the sweeps that have made it harder for unhoused residents to connect with social service providers, and ultimately, housing.

"I honestly think he has a disdain for people who just don't fall into a certain socio-economic category," Peterson said, adding, "I think he has criminalized people for being unhoused."

Britta Fisher, the first and former head of the Department of Housing Stability and the current head of the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, points to progress on homelessness made under Hancock's years in office.

"We have a much more robust shelter system at the end of the Hancock administration than was ever really contemplated before in Denver," she said.

Hancock created the Department of Housing Stability in 2019 to implement his housing policy. Over his three years, his administration helped fund more than 10,000 units of affordable housing -- some units were for the most vulnerable but many were for the workforce struggling to stay in town.

The number of homes he has created is a fraction of the 60,000 units needed, and that number will only continue to grow, according to David Nisivoccia, the outgoing head of the Denver Housing Authority.

During the pandemic, the city worked with nonprofits to open the shelters year-round, 24 hours a day and seven-days a week. Many of those efforts were funded through dwindling federal pandemic emergency funds but also city money through the Homelessness Resolution Fund.

The city also helped fund non-congregate shelters, spaces where people experiencing homelessness could live alone while they identified more permanent housing.

"It was a powerful combination to get people to the right health solutions, to get them stabilized, connected to appointment-based care," Fisher said. "It wasn't housing, but it was sure acting a lot more like it than a shelter bed."

Like Hancock did in 2011, Mayor Johnston is inheriting a city on a growth trajectory.

Downtown could double in population. The River Mile development on the current Elitch Gardens site will bring 15,000 people downtown, according to the developer Revesco Properties. The Ball Arena parking lot is slated to become a live-work-play community, adding 6,729 units, according to plans submitted to the city, and Coors Field will likely be connected to Broncos' stadium by a so-called "Sports Mile." Sun Valley's redevelopment continues to rise.

Hancock's Aerotropolis, growing near the airport in Denver and Adams counties, will continue to be built. Cherry Creek is experiencing an overhaul. And Southeast Denver is booming near the Denver Tech Center.

Barnum, Westwood and Northeast Park Hill are being eyed for development, as is Burnham Yard.

But as Hancock leaves office, homelessness, eviction and affordability are the most immediate issues on Denverites' minds. Johnston hinged his campaign on solving them.

The incoming mayor has committed to build 25,000 units of permanently affordable housing and end homelessness in four years by constructing 1,400 tiny homes. That's a pittance of what's needed for the 27,860 people who experience homelessness in the Denver Metro in a year, according to the Metro Denver Homeless Initiative 2022-2023 report.

Many, including Kniech, have said Johnston's goals are unrealistic and unhinged from the reality of funding, available land and the community's desires.

How does Hancock feel about Johnston's aspirations? First off, he says he's glad Johnston won, but time will tell how the new mayor does.

"I didn't understand, until I became the mayor, the true realities of your limited resources, the real dynamics of communities who pushed back on the concept that you're going to bring a tiny home village to my community," Hancock said. "We found it out. It's not as simple as people think it is. It's very complex. You're dealing with a lot of human-condition issues, and people are concerned about those conditions coming into their communities and the unknown. And they push back, and they push back hard."

Lafferty, of Habitat for Humanity, said Denverites will need to shift their perspectives if Denver is to solve its affordable housing crisis.

"We have to be willing to vote and accept more density," she said. "We just do. You can't have one without the other. And, you know, I would have liked to have seen the [Hancock] administration embrace that more. But there's not many elected officials who are willing to go there."

Denver is limited in its ability to acquire new land and also lacks space to build tiny homes and permanent housing projects, said Hancock.

"The assessment of our inventory of land that we could possibly do these sort of things on, we did six, seven years ago," he said. "And that land that we had, we either had tiny home villages or we have helped to build affordable housing on those pieces of land -- or shelters. And so there's no land. We've done it."

All that considered, does Hancock think the next mayor can end homelessness and make the city affordable again?

"I wish him the very best," Hancock said. "I'm not the doubter. I love those kinds of grandiose ideas. If you don't have big, hairy, audacious ideas, then what do you have to pursue? So go do it. And hopefully you'll do something that no other city in the world has been able to do, and that is to end homelessness."