Updated on Aug. 28:

Just 13% of historic designations in Denver preserve the history of historically marginalized communities. On Monday, the city added a new site to that group, when City Council voted unanimously to landmark civil rights attorney Irving Andrews' home at 2241 York St.

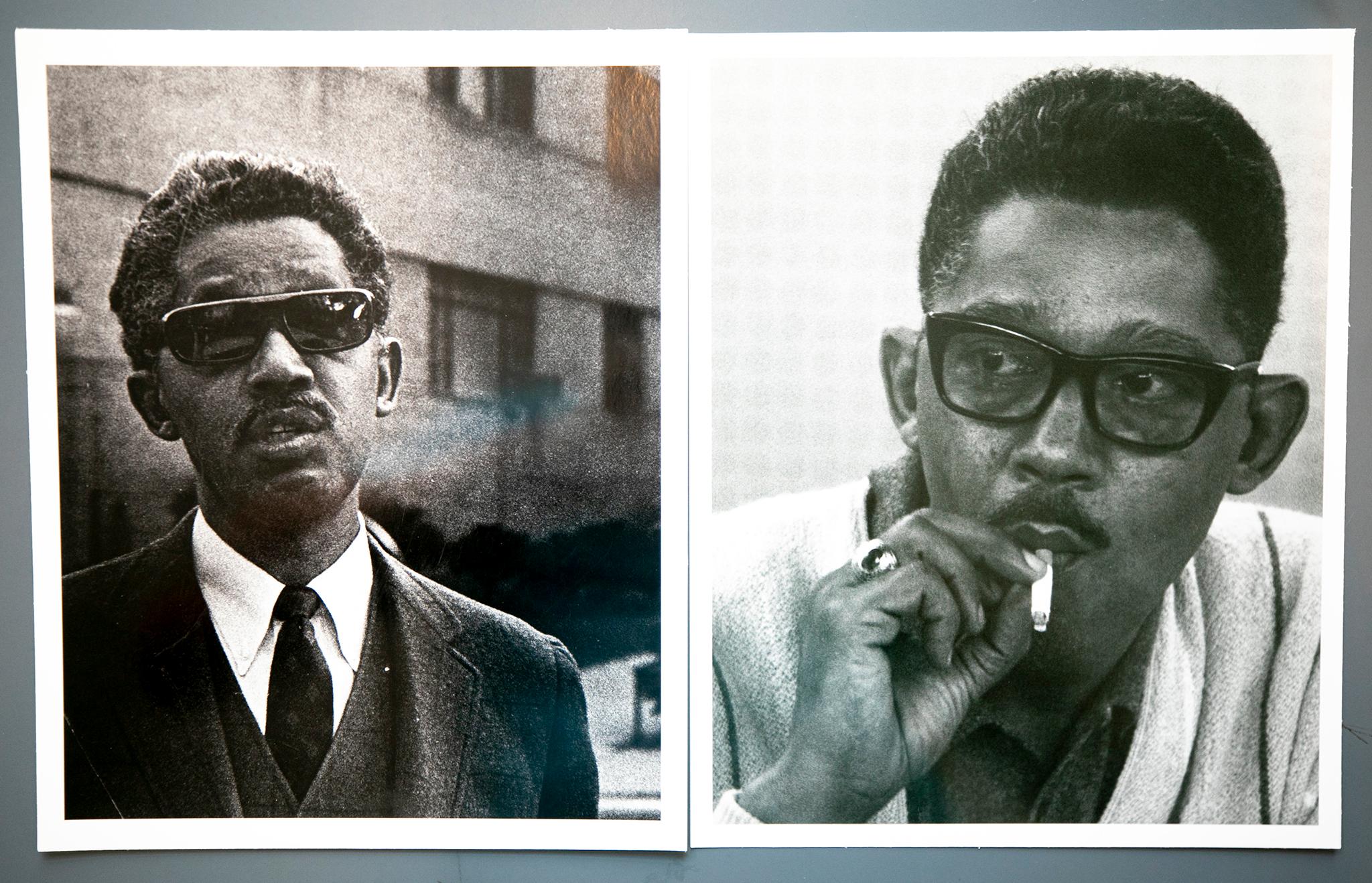

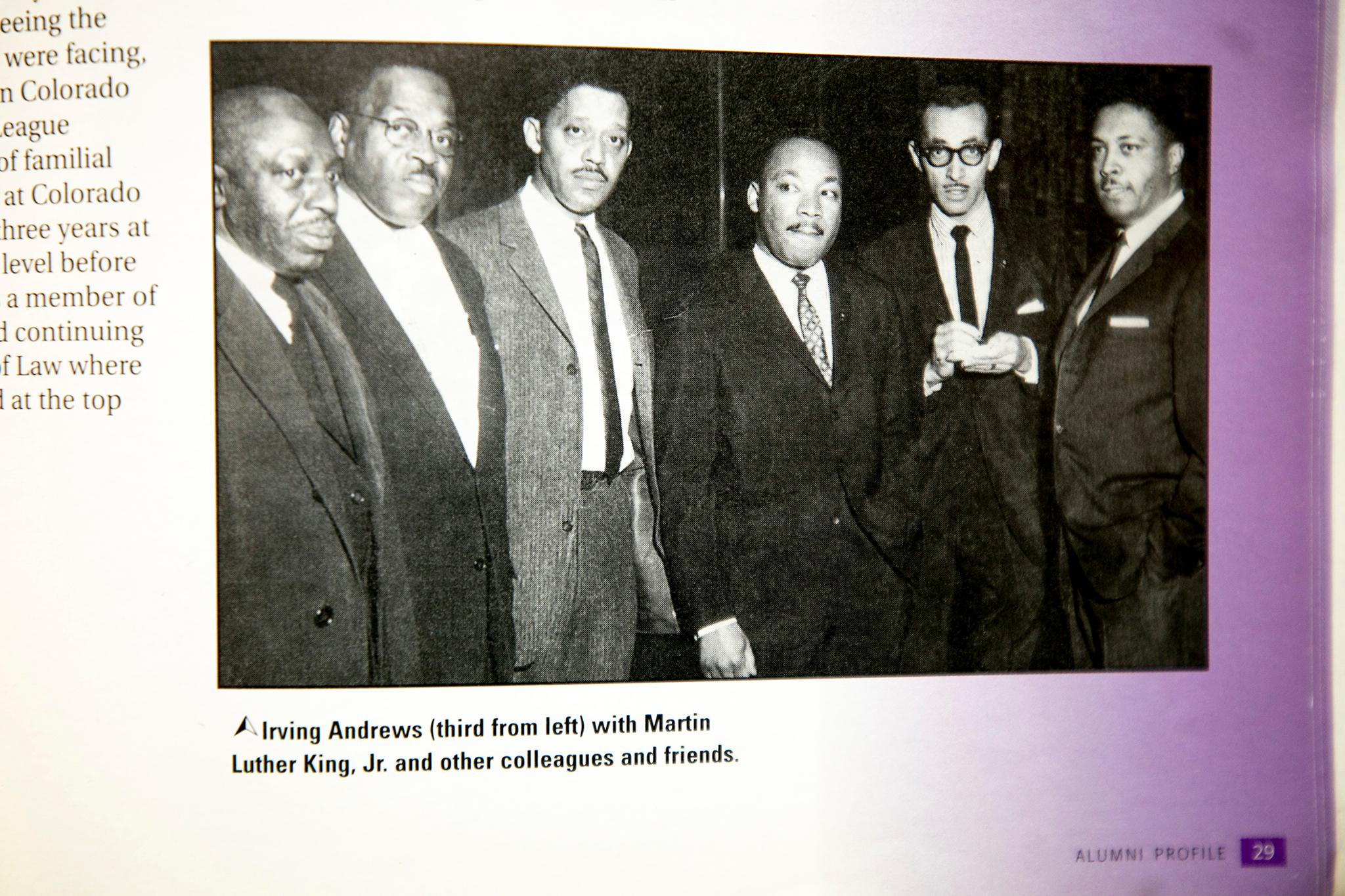

Andrews has a long pedigree in Denver: he opened the city's first racially integrated law office, was part of the legal team that tried Brown v. Board of Education before the Supreme Court, organized civil rights protests, defended activists and marched with Martin Luther King Jr.

When Andrews first moved into his home in 1972, segregation prevented him from opening his practice downtown. So, his house in City Park West doubled as his office. Now, that home and office is a city landmark.

"The significance of this home... is really the fact that it represents the history of Denver, a city that you don't think of like Atlanta, like places in the South having segregation," said Andrews' daughter Liz Andrews during the City Council meeting Monday. "The movement for Civil Rights, the movement for equality was not just something that happened in the South, on the East Coast. It happened right here in Denver, Colorado, in fact, on 23rd and York Street."

The original story follows below.

When civil rights attorney Irving Andrews moved into his City Park West home in 1972, the same segregation he fought in the courts barred him as a Black man from opening a law office downtown. So he opened his office on the upper floor of his home at 2241 York St.

Andrews died in 1998, and now, his home might become a city landmark.

On Tuesday, the City Council's Land Use, Transportation and Infrastructure Committee approved the application brought by current owners, his wife Sara Shears and daughter Liz Andrews. The request will come before all of Council for a vote in the next few weeks.

Andrews had a prolific career, according to historic research from the Landmark Preservation Commission, Historic Denver and the Denver Public Library archives.

He was part of the legal team that brought Brown v. Board of Education before the U.S. Supreme Court, a landmark ruling that determined segregation in public schools was unconstitutional.

"Law students would often skip class to witness him in court demonstrating his impressive skills, such as quoting scripture, classical philosophers and legal precedents - all from memory - during his oral arguments," wrote the owners and Historic Denver in the application. Denverite has reached out to Shears and Andrews for further comment.

He opened Colorado's first integrated law firm, organized civil rights protests, defended activists in court, marched with Martin Luther King, Jr. and served as president of the NAACP in Colorado and Wyoming. Former Mayor Wellington Webb made Feb. 7, 1997 "Irving Andrews Day."

"We tried one civil rights case to verdict and left immediately to attend the 1963 'March on Washington,'" wrote Judge John Kane, Andrews' former legal partner, in an article for the Colorado Bar Association. "We sat within fifty feet of Martin Luther King, Jr. when he delivered his 'I Have a Dream' speech. We returned the following Monday to try yet another case. Such were the times."

Landmarking Andrews' house would also be notable for another reason: only 13% of historic designations in Denver commemorate "historically excluded communities," according to Community Planning and Development.

The other 87% represent the "history of white males." Andrews' house would join eight other landmarks commemorating Black history in Denver.

"Thank you for making sure that that we're not just telling the story of prominent white men in Denver," said Councilmember Amanda Sandoval during the committee meeting. "That's not my lived history.'"

To receive landmark status, buildings have to meet at least three of 10 criteria for historic designation. In this case, the landmark commission said the house was associated with an influential person and with a significant social movement. It also met the criteria for architectural style, as a Queen Anne-style home popular before World War I. It is an example of an early duplex in Denver, at a time when many other houses in the area were large single-family homes.

"Although he was not the first African American to move on to New York street, or even into this house, Andrews' purchase of the property at 2241 for his home and law office represents the culmination of two decades of advocacy for equal rights and his particular interest in housing equality," said senior city planner Becca Dierschow in a presentation to Council Wednesday.

But Andrews' purchase of the house was underscored by the fact that it doubled as his office.

"When you think 1972, it still strikes you as amazing at that point that an attorney of such great renown, such great everlasting impact on our country and how we live and who we are, couldn't hold an office, a law firm in downtown Denver," said Councilmember Darrell Watson.