Updated 2 p.m. on Aug. 20, 2025.

Last year, then-candidate Donald Trump told a crowd in Aurora he would ramp up deportations if he won the 2024 election. Federal agents arrived in Colorado soon after he took office, driving military vehicles across Aurora and Denver in high-profile raids.

The metro hasn’t seen such a public show of force since February, but data show U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has been more active in the metro ever since. Federal officers are arresting about five times as many immigrants in the city of Denver now, compared to averages before Trump took office.

That’s according to new numbers from the Deportation Data Project (DDP), an effort led by academics and attorneys to bring transparency to the nation’s immigration enforcement system. The dataset contains individualized records of encounters, arrests and detainments across the country.

ICE arrests have risen faster in Denver than elsewhere.

Nationwide, immigration agents are detaining three times more people than they did before President Trump took office.

Under President Joe Biden, federal officers arrested an average of about 9,000 people per month, according to DDP data that began in late 2023.

In June, under Trump, they arrested 30,000 people.

Local arrests have grown at an even faster clip.

ICE data is broken down into “areas of responsibility,” which extend from major U.S. cities. Under Biden, ICE reported about 140 arrests per month in the Denver-based region, on average. That number has risen above 500 in recent months.

The Denver “area of responsibility” includes all of Colorado and Wyoming. In total, it has seen about 2,900 immigration arrests this year.

Immigration is a civil matter, which means ICE arrests and detainments aren’t necessarily related to crimes. In the past, a criminal conviction could draw ICE’s attention, but people who otherwise followed the law were generally left alone.

That has changed. Today, federal agents are being encouraged to detain anyone who might qualify for deportation. That includes people who are still waiting for asylum requests to conclude in court.

Noncitizens arrested by ICE are placed in immigration detention. Those with final removal orders, as well as certain others, may be deported quickly. Others may be held indefinitely while their cases continue through the immigration system.

The records suggest that immigration agents are increasingly focused on the city of Denver. Between Sept. 2023 and December 2024, Denver represented an average 34 percent of all apprehensions in the broader area of responsibility. In June and July, that figure was closer to 50 percent.

ICE did not respond to a request for comment.

It’s worth noting: While ICE arrests have risen in recent months, ICE’s reported encounters with immigrants have remained relatively flat in the last few years, at an average of 1,300 per month for the region.

Still, the region makes up a relatively small proportion of ICE’s nationwide arrests. For example, the Miami area has seen more than 15,000 arrests this year, though it covers a far larger total population.

Jennifer Piper, a longtime immigrants rights organizer with the American Friends Service Committee, said arrests in Colorado and Denver are being slowed by laws that restrict local law enforcement's communication with federal agencies.

Yes, she said, her organization has seen local arrests rise. But she also said she's seen worse in Colorado, particularly between 2006 and 2013, when Presiden Barack Obama was known as "deporter-in-chief" and Colorado police departments had to inform federal agents if they encountered someone with an immigration infraction.

"Even if the numbers are accurate," she said, "it's still so much lower than when we had laws that required law enforcement to be part of this."

Meanwhile, Trump officials have talked about making even more arrests. “Border czar” Tom Homan has said his agents should be detaining as many as 7,000 people per day, about seven times the recent peak.

Piper said the agency has changed tactics to make their arrests more visible.

"Part of the administration's goal is to make us believe it's inevitable and that theres nothing we can do about it," she said. "There are things we have done and can do — and they're making a difference."

More people are being arrested before their immigration cases have concluded.

Since late 2023, when DDP’s data begins, ICE arrests in Denver have mostly focused on people with “final deportation orders” — people who have gone through the nation’s sprawling immigration legal system, who were denied a permanent stay and then were told to leave. That includes asylum seekers whose claims were denied by judges and people who committed crimes and lost their temporary rights to remain in the country.

But that trend inverted in July, when arrests of people without final deportation orders rose well above those marked for removal. The government can hold people while their cases are pending.

Laura Lunn, an attorney with the nonprofit Rocky Mountain Immigrant Advocacy Network, said the federal government is catching people in a wider dragnet.

“We're seeing ICE making a lot of collateral arrests, where they just start picking anybody up who's in the general vicinity when they're engaging in an enforcement action,” she said.

“We have seen a huge uptick of people winning their cases and ICE is not releasing them,” Lunn added.

“So people have won protection. They've demonstrated that they will more likely than not experience persecution or torture in their home country. And ICE has not disputed that, they have not appealed the judge's order. And nevertheless, they're saying, well, ‘We can't deport you to that country, but we're going to try to deport you to a third country, and so we're just going to detain you.’”

Between September 2023 and December 2024, on average, 57 percent of people arrested by ICE in Denver had been convicted of a crime or had pending charges.

In July, just 30 percent of those arrested were involved in any criminal prosecution.

What the data tell us about who is being arrested:

Men represent 80 percent of arrests in Denver in 2025.

Agents have picked up people of all ages, including one man who was born in 1934 and 13 children born since 2020. The majority were born in the 1990s.

People from Latin American countries make up most of this year’s arrests in the city — from Mexico, Venezuela and Colombia — but data also show people from places like Afghanistan, China and Romania have also been swept into the operation.

The metro’s main immigration jail is full, which means people are being whisked out of state when they’re arrested.

The metro is home to one large ICE detention facility in Aurora, which is run by GEO Group. The private prison company has been in the crosshairs of advocates like the ACLU for years. U.S. Rep. Jason Crow, whose district includes the facility, has been fighting to visit the detention center in recent months, since its operators stopped allowing him to tour it unannounced.

Crow recently said ICE is holding about 1,300 people in Aurora. Data compiled by Vera, a criminal justice reform organization, suggest that would be an all-time high.

Lunn, who’s spent years working with people detained in the prison, said the high detention numbers have led to deteriorating conditions.

“The population is pretty high. What we're hearing from clients is that the amount of food doesn't appear to be increasing, and so they're getting smaller portions as a result of more people being there,” she said. “We hear that the air conditioning is regularly broken and it takes three to four days for it to get fixed.”

Christopher Ferreira, a GEO Group spokesperson, pushed back on that, saying the company adheres to "strict" standards set by ICE.

"In the event issues are identified, we quickly resolve all of ICE’s concerns as required by the ICE’s Quality Assurance Surveillance Plan," he wrote in a statement. "Our contracts also set strict limits on a facility’s capacity. Simply put, our facilities are never overcrowded."

Lunn said she’s also heard of more people being sent quickly out of state after they’re arrested, separating them from both their families and their lawyers. “ICE is saying it's because they've run out of space at the Aurora facility,” she said.

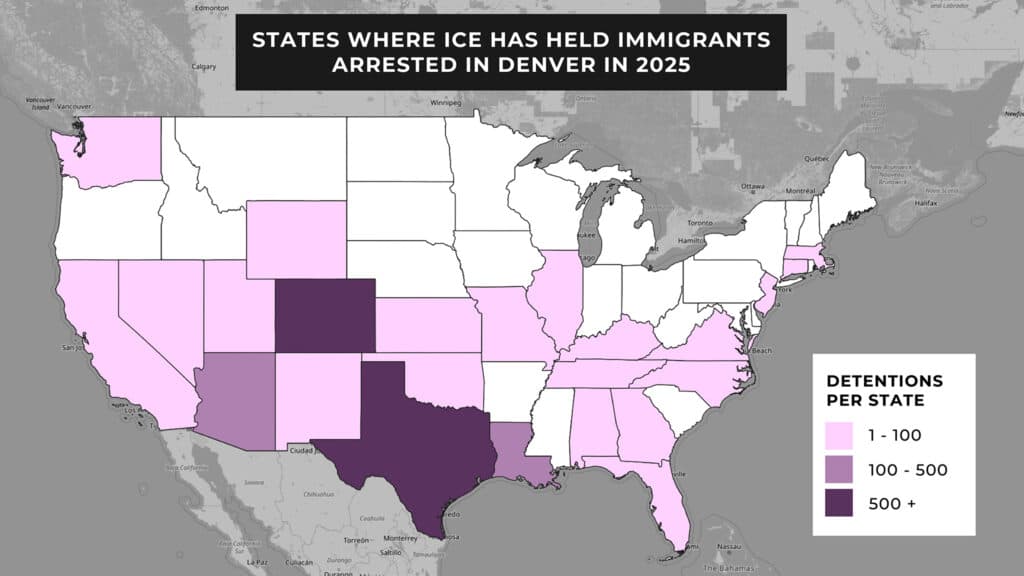

People arrested in Denver this year have landed in detention centers in 24 other states. Some could be sent to large lockups, while in other states, like Wyoming, they’re being held in county jails rented by ICE.

Records suggest one person was sent briefly to the U.S. military base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

The civil immigration enforcement system is different than the federal judicial branch. Other than crimes, like repeatedly entering the U.S. without authorization, all aspects of immigration are civil matters and under the control of the executive branch, headed by Trump.

That allows Trump’s administration to block bonds for many incarcerated immigrants and fire immigration judges who might otherwise shepherd people through the system, either to deportation or release.

The entire immigration legal system, Lunn said, is “being dismantled in a way that makes it incredibly hard for people to gain access to justice.”

“If one person's due process rights are being taken away, then that is a problem for all of us, because it's an erosion of our rights,” she said. “That should be reason enough for people to pay close attention to what's happening right now.”

Editor's note: This story was updated with comment from Jennifer Piper and Christopher Ferreira.